China is officially honoring a reformer today whose death sparked the Tiananmen Square protests

Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Hu Yaobang, the reformist Chinese official whose death triggered the wave of student protests in Tiananmen Square that ended in the deadly June 4, 1989 crackdown. Rather than ignoring the occasion, though, China is officially remembering Hu with speeches and symposiums.

Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Hu Yaobang, the reformist Chinese official whose death triggered the wave of student protests in Tiananmen Square that ended in the deadly June 4, 1989 crackdown. Rather than ignoring the occasion, though, China is officially remembering Hu with speeches and symposiums.

China’s president and general secretary of the Communist Party Xi Jinping attended an official commemoration (link in Chinese) for Hu at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing today as he returned to the capital Thursday (Nov. 19) after attending the APEC summit in the Philippines.

Although Hu now commands respect from the highest level of government, the party earlier condemned him for tolerating “bourgeois liberalization.” His legacy on economic reforms and anti-corruption are in tune with Xi Jinping’s own. But as a liberal and non-dogmatic leader, Hu is hardly a perfect political symbol for Xi’s government to promote, as it continues to exert tight controls on ideology and freedom of speech.

This contradiction is reflected in how the party has spoken of him since he was forced to resign from the position of general secretary in 1987. After having clashes with Deng Xiaoping and other Party elders on economic and political reforms, Hu’s political opponents claimed Hu’s “laxness” and “bourgeois liberalization” led to and worsened a 1986 student pro-democracy protest in Tiananmen Square. At the time he confessed to so-called “mistakes on major issues of political policy,” but the party has never reiterated his mistakes ever since then.

After Hu died of a heart attack in April, 1989, thousands of Chinese students rallied on the streets to mourn him. The mourning transformed into the Tiananmen pro-democracy movement. A military crackdown on June 3 and June 4 led killed hundreds, and possibly thousands, of demonstrators.

Hu’s name became taboo after that. The Communist Party held any official commemoration until 16 years after his death. On the 90th anniversary of his birth in 2005, a memorial event was held at the Great Hall of the People with then-premier Wen Jiabao and vice-president Zeng Qinghong. Though then-president Hu Jintao sanctioned holding the memorial early that year, he didn’t attend the event.

There has been more openness about Hu in recent years—with Chinese netizens commemorating him on the Chinese microblogging site Weibo without being censored, and state-backed media publishing eulogies and stories on his legacy.

This year things seem more open than ever. Two days before his memorial, an editorial (link in Chinese) published on the state-run tabloid Global Times wrote the party was not incorrect in dismissing Hu at the time. But his”brilliant image,” the editorial wrote, has been going through “the whole process of China’s reform and opening-up,” which is “both admirable, and making people have all sorts of feelings.”

Hu’s hometown Hunan province held memorials earlier this week, as well as Jiangxi province where he was buried. On Nov. 16, China’s top Communist Party school held a memorial in Beijing.

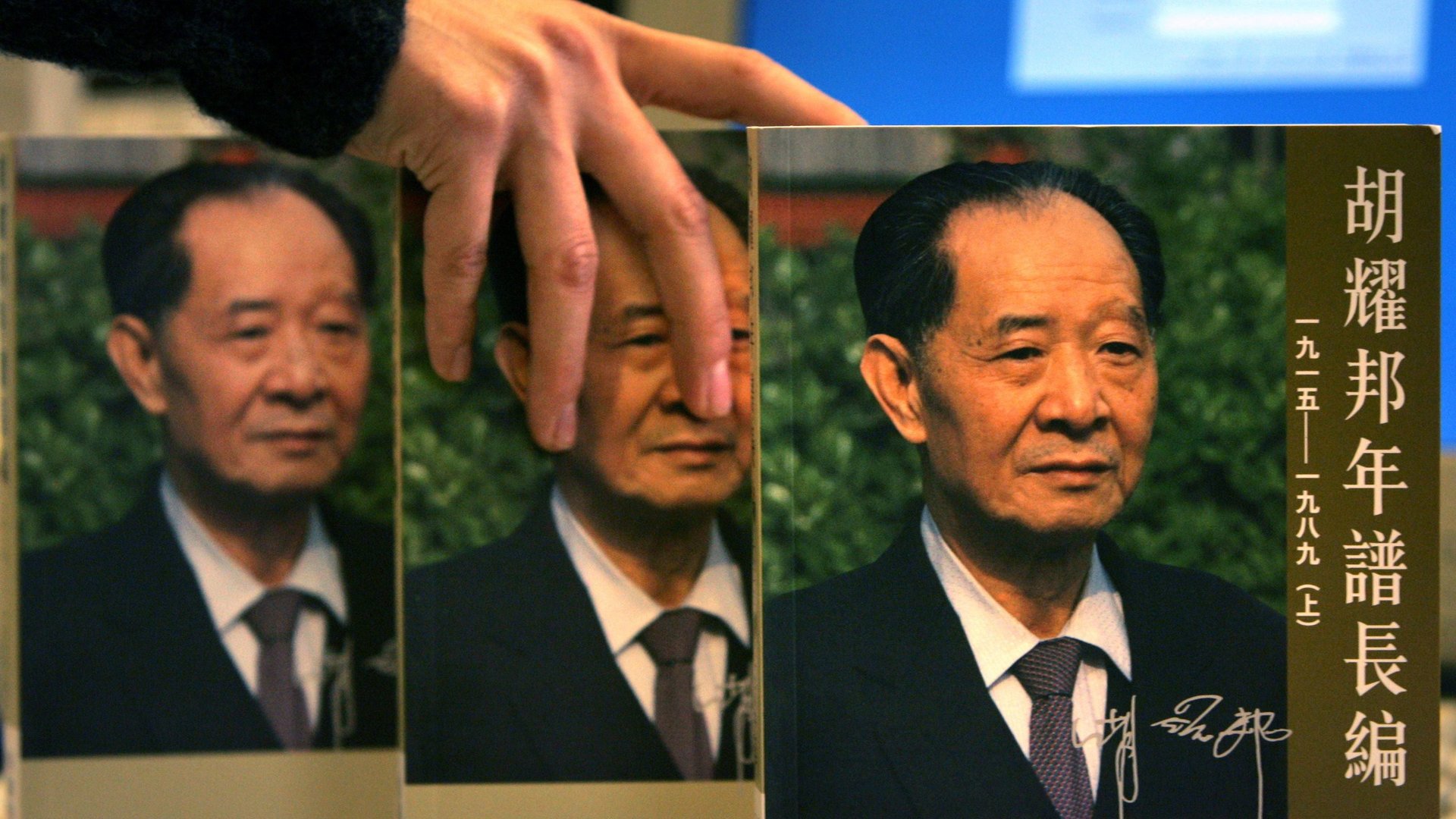

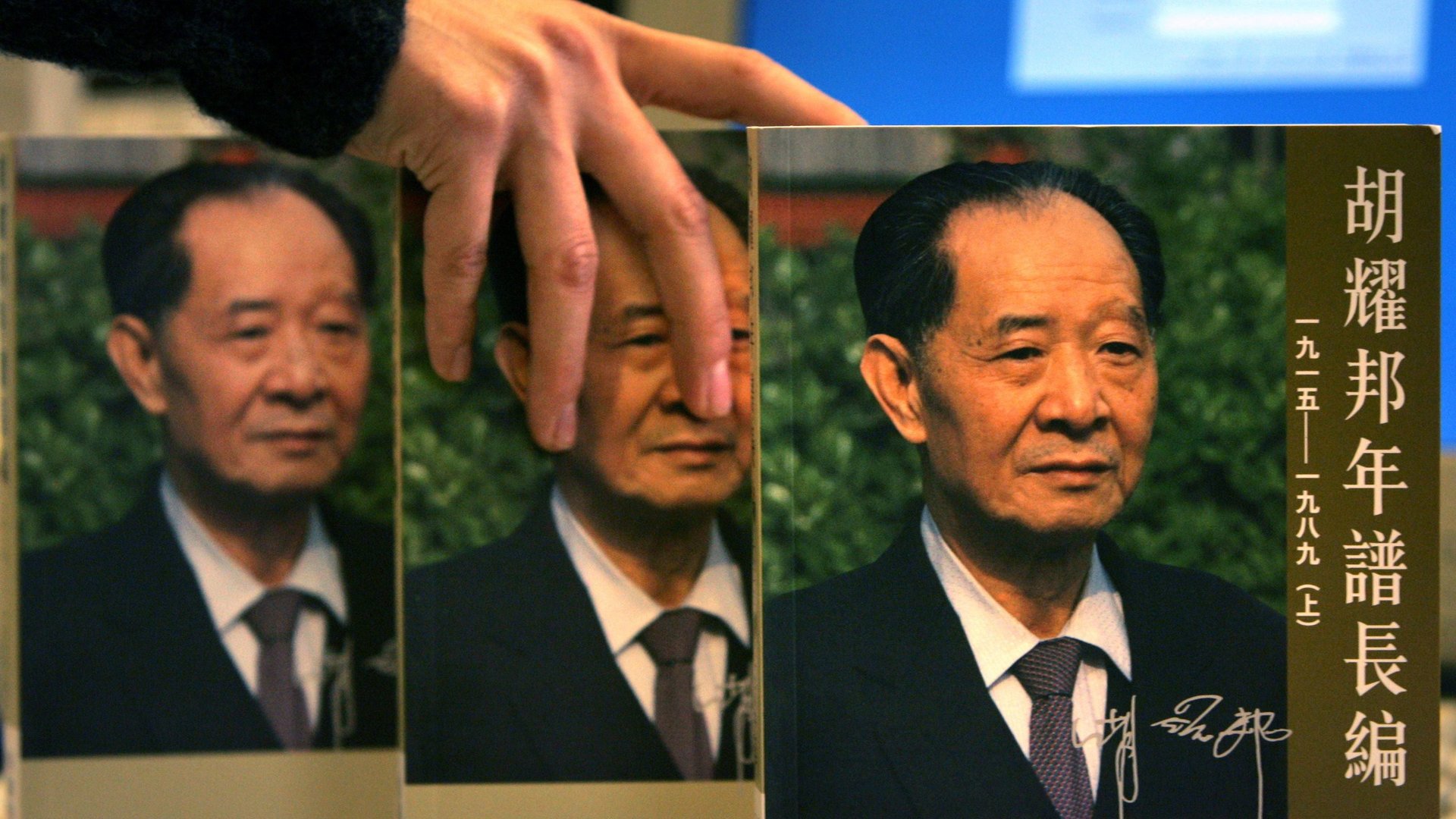

A collection of Hu’s speeches and writings—many are seen by the public for the first time—was published on Nov. 19. These sorts of books about departed Chinese leaders are carefully chosen and endorsed by the party.