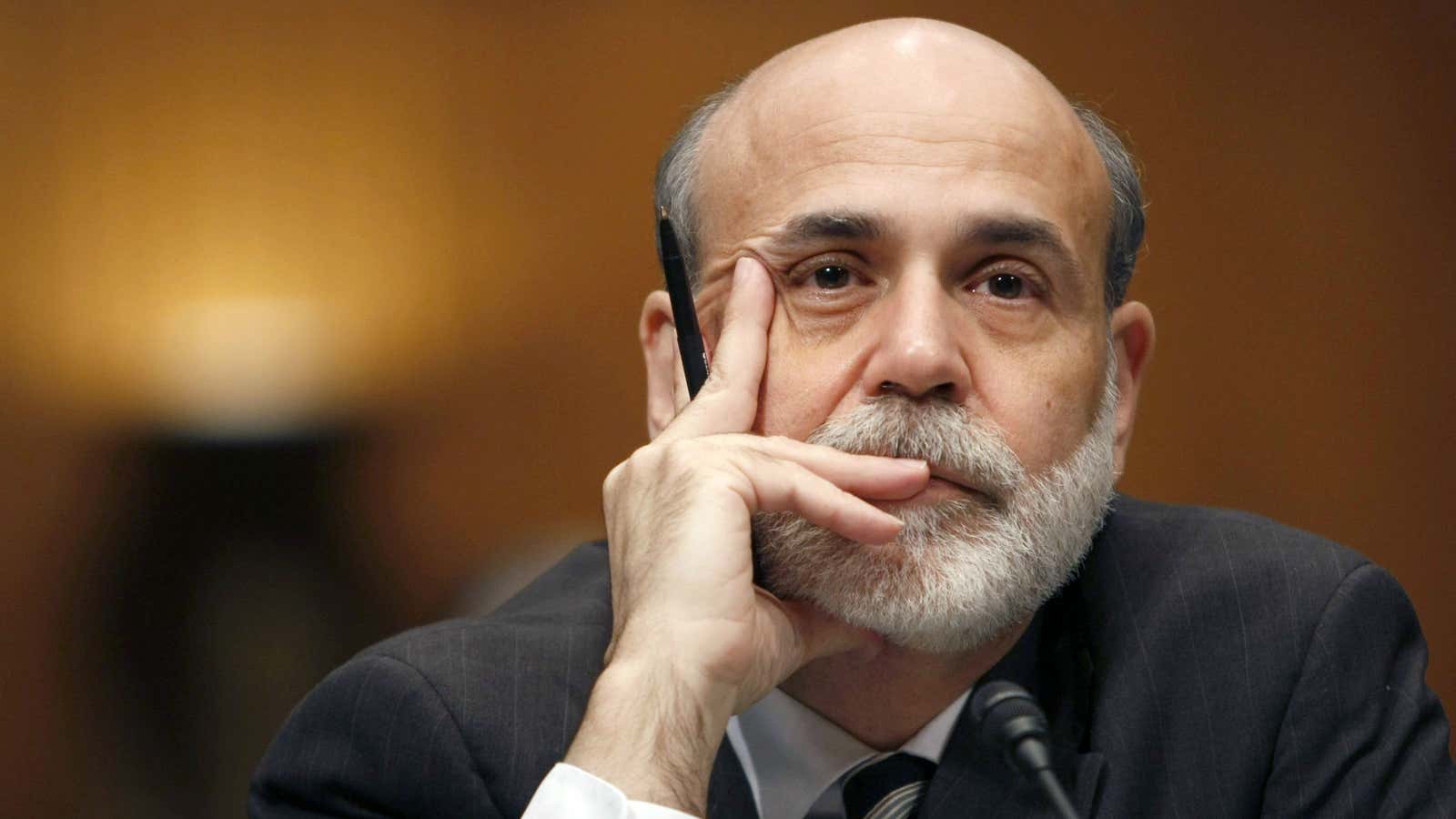

Ben Bernanke was arguably the most powerful person in finance at the exact moment finance, essentially, broke.

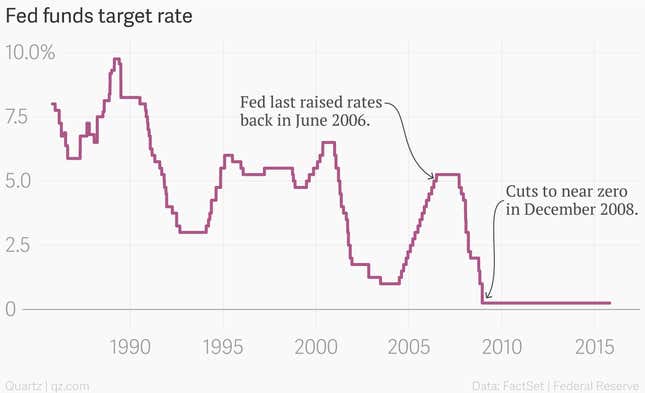

The institution he had led since 2006, the Federal Reserve, was the world’s most important central bank, with wide-ranging responsibilities influencing financial markets, financial institutions, global economic growth, and the US dollar.

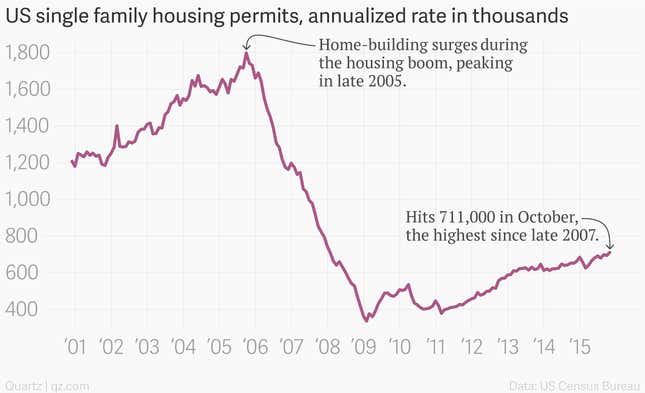

As such, he was at the center of the tension as the US financial system first bent under the growing load of bad mortgage loans, and ultimately fractured with the bankruptcy of US investment bank Lehman Brothers in September 2008.

Lehman’s collapse precipitated the worst financial crisis and recession in the US since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In his recent book, The Courage to Act, Bernanke writes about what it was like at the center of the storm. And he explains how he and other policy makers such as Treasury Secretaries Henry Paulson and Tim Geithner groped for approaches that would first stop the crisis, and eventually push the US economy back to growth.

While the book has no shortage of references to the parade of government programs aimed at stopping the crisis—TARP, HARP, HAMP, Quantitative Easings, Operation Twist, among them—the memoir is also a highly readable account that adds a sorely missed perspective to the growing pile of post-crisis postmortems. It also gives you a flavor for Bernanke the man, especially some of his eating habits, including an early affinity for Hot Pockets.

Quartz recently chatted with Bernanke—now a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Institution—by phone, in order to take his temperature on a range of issues, from frothy valuations in Silicon Valley to his change of heart regarding healthy eating. Here’s our chat, lightly edited for concision and clarity.

Quartz: One of the newsier bits to come out of your book was that you’re not a Republican any more, you’re now an independent. You say you “lost patience with the Republican susceptibility to the know-nothingism from the far right.”

As former head of the Fed, I know you know how to use more obscure language than that. But you say this pretty clearly. Why?

Bernanke: Well, the question comes up a lot. I’m a moderate. I believe in the market system. But I also think that the Federal Reserve is a very important institution, which has in general played a constructive role in our economy.

And I’m concerned about some of the extreme views about the Fed and our monetary system that have been espoused. I haven’t really changed my position much. I’ve been concerned about the populism both on the right and the left that has implications that worry me in terms of our economy.

In my view, the Fed’s efforts to help the economy were kind of cynically seen as something that would not only help the economy but potentially the president. (Because rightly or wrongly, presidents tend to get credit for whatever the economic performance is during their tenure.) What’s your feeling about that? Am I correct or am I off base?

Well, I mean, first of all, the goal of the Fed is to help the economy prosper. And if that benefits politicians, that’s fine. But, you know, what’s the alternative? To avoid helping the economy so that you don’t help politicians in power? I don’t understand that.

The goal of the Fed and the monetary policy is to promote prosperity—whoever is president. And, in my case, I was appointed by President Bush and I was reappointed by President Obama. And I worked constructively with both men. And I was engaged entirely in the effort to help our economy recover from the great recession, and I wasn’t interested in politics.

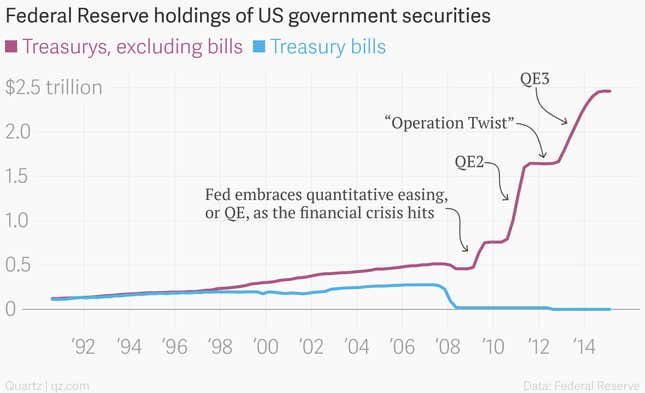

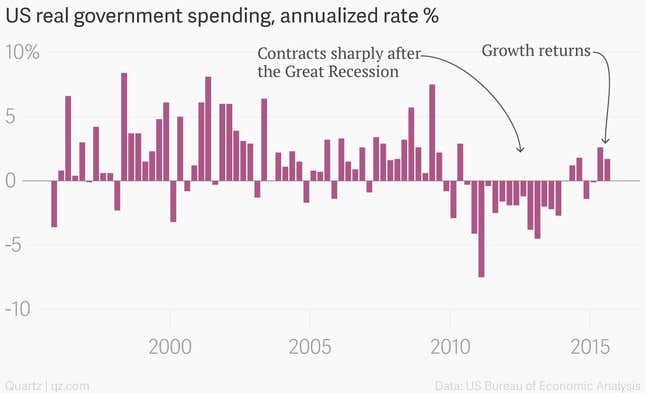

I worry that there’s a free-rider problem in the interaction between governments and central banks. For instance, in the UK, the government has run a pretty tight fiscal policy, essentially relying on the central bank to keep the economy moving forward. And there’s been an element of that in the US, too. Congress and the Obama administration didn’t really do very much to support growth in the aftermath of the crisis. And the Fed pretty much did most of the heavy lifting. Is there a free-rider problem?

Well, to some extent, that’s true. Fiscal policy was too tight during a good bit of the recovery, and that left the heavy lifting, as you say, to be done by the Federal Reserve. I think, in general, governments have relied too heavily on central banks. And we’ve therefore had a less vigorous recovery, and a less balanced policy response than we otherwise would have had.

Then the question is: What should the the chairman of the Fed do about that? I talked about it frequently. And I urged Congress to avoid cutting too aggressively in the budget or raising taxes too aggressively. And in particular to avoid things like failing to raise the debt limit, which created a lot of volatility in financial markets.

So I urged congress to shoulder its share of the burden, but I don’t think it was my role or the Fed’s role to dictate to Congress. It’s Congress’ decision about what policies they’re going to enact. And it’s not the Fed’s job to threaten to withhold its proper policies until Congress does its bidding. That’s simply not what happens in our democracy.

There are some interesting things in your book about your management style and how you chose to run the FOMC. For instance, you made a point of deciding that you would speak at the end of the FOMC meeting rather than at the beginning as your predecessor Alan Greenspan did. Are there any other lessons or tools that you used as the leader of the Fed that you think could translate to other leadership positions?

Well, I think leadership is a personal thing. And different personalities approach it different ways. My background was as an academic, I was chairman of the economics department at Princeton. And I was used to dealing with peers, people who had strong opinions and couldn’t be told what to do, basically. So my approach was to pick a collegial approach and to try to make sure everybody’s views were heard and that we developed consensus for our policy choices.

Now I think that was helpful in building capital—personal capital—because at times during the crisis we had to act more quickly without taking the time to build consensus.

And I think at least to some extent, the fact that we had built a collegial consensus initially gained me some more leeway to what we had to do during the crisis.

When I came into the chairmanship, Chairman Greenspan had of course been a very effective leader. But at times, I think that people began to identify the Fed with one person, with the chairman. And I think it was important for the public to understand that there are a lot of talented people at the Fed and that decisions are made in a collective, collegial way. And I wanted to push that perspective.

The US economy seems to be doing well on a lot of fronts right now. But we do seem to have areas where the market may have gotten ahead of itself. Bubbles continue to emerge. To a certain extent it seems that this is just a feature of capitalist economies. Do you see areas of concern right now in terms of bubbles?

I should first say that the Federal Reserve has become much more involved in monitoring the financial system and in trying to identify potential problems. But the Fed’s perspective—and my own—is not necessarily to worry if some class of assets is mispriced. Rather, the question is: Are there building threats that could actually endanger the overall system, like the housing bubble and subprime mortgages did in 2007?

So on that criterion, I don’t see any big asset class that’s badly overvalued. Nor do I see any obvious areas where the financial system is vulnerable to a financial crisis. There are certainly areas where investors need to be cautious and to pay attention.

Many people have made the argument that in Silicon Valley, there’s really wild valuations on some really speculative new firms. I know you don’t speak for the Fed, but from a policy maker’s perspective, your concern is not if some venture capitalists lose a lot of money.

That’s exactly right. And I would say that thinking about the housing bubble before the financial panic. I think in retrospect that we at the Fed and other policy makers spent too much time debating whether or not it was a bubble or, if it was a bubble, how big it was. Instead I think the better way to think about it would have been to ask the question, “We don’t know if it’s a bubble, but suppose it is? And suppose that it were to burst spectacularly? What would be the worst thing that could happen?” In other words, to trace the implications of a big movement in an asset price, for the banking system and the financial system more generally. And I think that’s the right way to think about this.

And so in the example you just gave me, I have no idea whether tech stocks are overvalued or not. There’s some people who think they are. On the other hand, it’s very difficult intrinsically to value such stocks because they are bets on the future. But be that as it may, my own sense would be that if the value of some unicorns [companies valued at $1 billion or more] went down that—while it would certainly matter to the investors and the entrepreneurs involved, as you say—it probably wouldn’t be a serious threat to the overall economy.

One of the things I’ve been thinking about is the political economy of bubbles. It seems like there’s very little incentive for anyone to actually try to pop a bubble, because you can’t take credit for averting a crisis that never happened.

Well, I think we’ve learned though that bubbles in some circumstances can be very dangerous, and affect not only the fate of investors but the whole economy.

And since the crisis there have been efforts around the world, to use what’s called macro prudential economies, to try to diffuse risks before they do damage. So, for example, my colleague Don Kohn, who was the vice chairman of the Fed when I was there, is a member of the British financial policy committee, which tries to identify such problems and, when it does, it makes recommendations to the parliament to impose restrictions. (For example, in the case of housing, higher down payments and more capital against mortgage loans, that can help constrain that bubble.)

And what’s important there is, first, that the bubble is identified by a set of experts—a set of policy makers who are focused on this issues—and, secondly, once the recommendations are made it’s a broader political decision, not just the central banking making the decision; it’s a broader decision made by policy makers and legislators about what to do about the problem.

All that being said, in the United States we haven’t set up systems like that. But we have tried to make our banking system and our financial system more resilient so that no matter what kind of shock might hit, our banking system is today much better able to weather it than it was eight years ago.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis there was a lot of handwringing about economics and the obvious failures of economic theory. It seems to me that while there some schools of economic thought that seemed to crumble in then face of the crisis, economic history held up pretty well. You’ve got a historical background in your studies of the banking crises during the Great Depression, do you see economic history making a comeback?

I don’t think it’s disappeared. It’s obviously only one part of economics. But I agree entirely with what you said. Knowledge of economic history is critical for good policy making because, as valuable as it is to understand models and theories, in real life policies have to be made in societies that are complex and have political and sociological considerations to take into account. History gives you a much better overall framework to think about some of these things. So in the case of the financial crisis, yes, what I knew about the depression and about financial panics prior to the depression was actually very helpful conceptually for thinking about this panic.

What do you think about bitcoin?

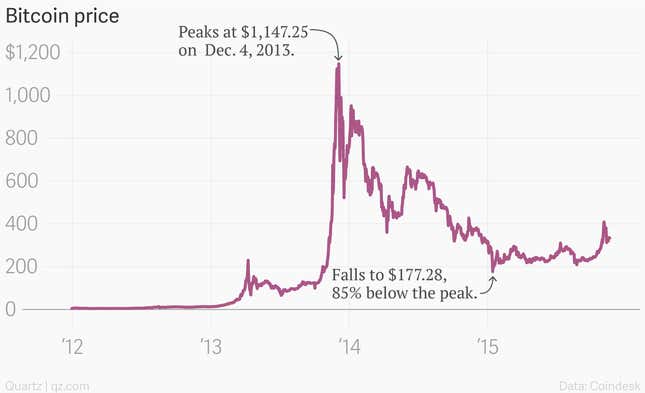

It’s interesting from a technological point of view. We’re in a world where the payments system is evolving quickly and new approaches to managing payments are proliferating, and some of the ideas around bitcoin will no doubt be useful in doing that.

But I think bitcoin itself has some serious problems. The first is that it hasn’t shown to be a stable source of value. Its price has been highly volatile and it hasn’t yet established itself as a widely accepted transactions medium.

But the real serious problem that it has is it’s anonymity, which is a feature, and is also a bug, in that it has become in some cases a vehicle for illicit transactions, drug selling or terrorist financing or whatever. And you know, governments are not happy to let that activity happen, so I suspect that there will be oversight of transactions done in bitcoin or similar currencies and that will reduce the appeal.

My last question might be the toughest one. Are you still eating Hot Pockets?

I am not. I am really into healthy eating now. And I decided that I would stay away from high fat types of products.

What’s your go-to snack now?

I don’t think I have one. I try to keep it down.