Israel is finally allowing Palestine to have 3G

One feature of Israel’s control over Palestine is its stranglehold on the mobile market. The two Palestinian cellphone companies, Jawwal and Wataniya, have to license their wireless spectrum from the Israeli government and route their traffic through Israel. And while Israel’s government granted 4G licenses to six Israeli mobile operators earlier this year, Palestinians have remained stuck two generations behind. Only today did Israel sign a deal with the Palestinian Authority that will extend 3G and maybe 4G to the Palestinian firms.

One feature of Israel’s control over Palestine is its stranglehold on the mobile market. The two Palestinian cellphone companies, Jawwal and Wataniya, have to license their wireless spectrum from the Israeli government and route their traffic through Israel. And while Israel’s government granted 4G licenses to six Israeli mobile operators earlier this year, Palestinians have remained stuck two generations behind. Only today did Israel sign a deal with the Palestinian Authority that will extend 3G and maybe 4G to the Palestinian firms.

Israel’s reasons for keeping Palestine on 2G up to now are not entirely clear. The Electronic Frontier Foundation suggested, in an analysis earlier this month, that less-secure 2G networks are easier for the Israeli authorities to monitor—or at least to monitor without detection, since surveillance might be a violation of the 1995 Oslo peace accords.

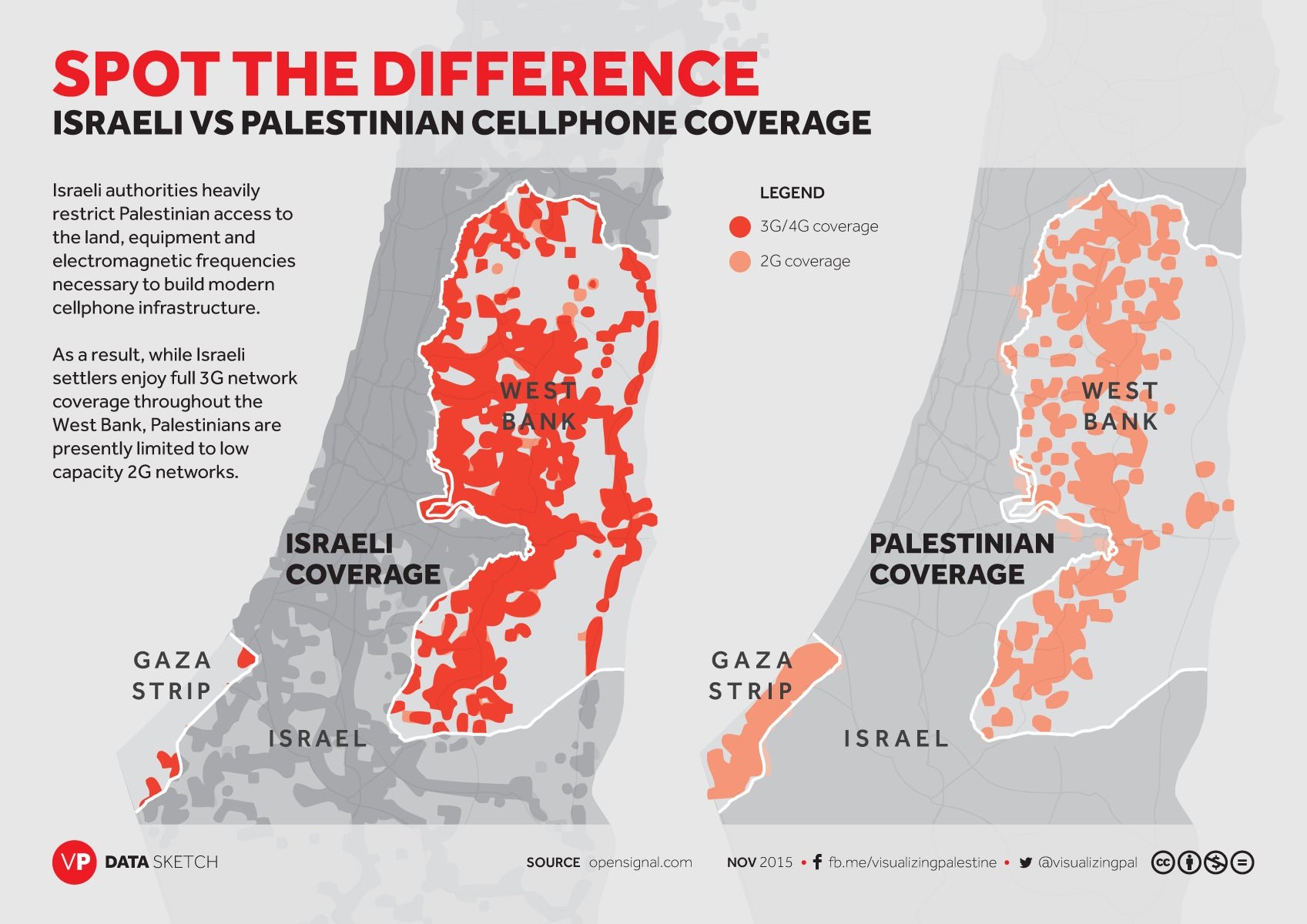

But there could also have been a commercial reason for holding 3G back. Israeli cellphone companies have extensive coverage in the West Bank, where they’ve been able to put cellphone towers in Israeli settlements—locations that, in the West Bank’s rugged topography, are prized because they’re typically on hilltops. As a result, they have better coverage in many places than Jawwal and Wataniya, as well as offering 3G or 4G:

Israel also keeps Jawwal and Wataniya in a chokehold in another way, by licensing far less spectrum to them than to Israeli firms. In the January 4G auction, Israeli companies bid on a total of 65 MHz of spectrum (on top of what they already had in 3G), to serve Israel’s population of 8 million people. Jawwal and Wataniya together have less than 10MHz, for a population slightly more than half that of Israel’s. Tight spectrum means slower connection speeds and more dropped calls.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that by one estimate, Israeli operators have 20%-40% of the Palestinian market (pdf, p. 11), costing the Palestinian providers $80 million to $100 million a year in potential business. And so there may well have been some pressure on the government to let the Israeli companies—which are also in such fierce competition with each other that not all of them are expected to survive—maintain their edge.

Why Israel is now deciding to let Palestine have 3G is also unclear, though it might be an attempt to improve relations after weeks of violence. Either way, it makes Palestine one of the last places in the world to get 3G. An spokesperson for the International Telecommunications Union told Quartz that at least 181 of the ITU’s 193 member states already have mobile broadband to some degree.