Why should Apple even bother building a car?

Having discussed the software culture challenge in a previous Monday Note, we now turn to a new series of questions regarding the fantasized Apple automobile.

Having discussed the software culture challenge in a previous Monday Note, we now turn to a new series of questions regarding the fantasized Apple automobile.

First: money

Take Ford, the healthiest of US automakers. (I won’t wade into the government loan vs. bailout money controversy.) The company’s latest annual report provides the following summary:

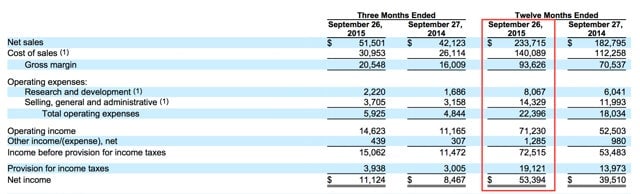

Apple’s fiscal 2015 numbers from its Oct. 27 8-K report look like this:

Ford’s revenue and operating income: $134 billion, 3.9%.

Apple’s corresponding numbers: $234 billion, 40%!

Or consider the world’s two largest car companies, Toyota and Volkswagen, both of which hover around $200 billion in revenue. Toyota just reported a higher than usual 10% net profit versus Apple’s 22.8%. The Financial Times recently pegged the VW brand’s operating margin at about 2%. (We’ll see how the German auto giant, which was ever so close to taking the industry’s Ichiban ranking from Toyota, extracts itself from its current engine management software troubles.)

Yes, the car industry is large (around $2 trillion—that’s two thousand billions), but it grows slowly. In 2015 it saw 2% annual growth—and that was considered a good year.

The question isn’t how Apple could make money with cars but: Why should it bother?

A possible answer resides in a look at the iPod’s history. When the iPod was introduced in October 2001, many scoffed at Apple’s entry into the MP3 player market, yours truly included: What are they thinking? You can’t make money in a market that’s already commoditized and saturated!

We now know the answer: design + iTunes + distribution. The iTunes ecosystem, music by the slice, micro-payments… the Apple Store revolution had begun, but we couldn’t see it.

Just as Apple managed to get much higher iPod margins than competing makers, can the Cupertino company do better than Toyota or Ford?

One way Apple could simplify the path to profits would be to offer a single model in a single color (rose gold, maybe; white, more likely).

In a sort of race to the bottom, competition entices today’s car manufacturers to offer entry-level models that depress their profit numbers—and are loathed by dealers. (More on them in a moment.) Going to a simplified “Ford T” product definition sounds more profitable—and more Apple-like.

Furthermore, automakers lead a complicated design life. The Financial Times article mentioned above lists the dizzying number of steering wheel choices for the Volkswagen Golf alone. Take a guess: 10? 20?

No: 117.

Take a look at any automaker’s website and you’ll see a similarly convoluted product line with logic puzzle options and configurations. It smells like product management—or, simply, management—run amok…

Another way Apple could win the profit game is by using its uniquely strong financial position ($205 billion+ in cash) to offer attractive terms to its suppliers. Going back to Ford’s numbers, one sees $7.4 billion in capital expenditures; Apple’s corresponding number is proportional after you adjust for revenue: $11.2 billion, with $15 billion planned for 2016. But Apple’s latest 10-K (yearly) SEC filing discloses another interesting number: Off-balance sheet commitments to suppliers that are much higher than capital expenditures: “As of September 26, 2015, the Company had outstanding off-balance sheet third-party manufacturing commitments and component purchase commitments of $29.5 billion.”

Apple’s ability to secure critical components at favorable prices for iDevices and Macs would certainly be replicated with chosen automotive parts suppliers and subcontractors.

With a much simpler product line and proven success with suppliers, Apple Car’s business could generate higher profits than legacy automakers. Of course, “higher” is vague—it doesn’t come with a precise value, or even a range. Today, Apple’s gross margin is about 40% of sales, and net income exceeds 22%. Can an Apple Car approach these numbers?

Second: weight—more properly referred to as mass

Mass is a crucial factor in the design of an electric car. At the same speed, (kinetic) movement energy is proportional to mass: 1/2*m*v^2. Accelerating a heavier car drains more power out of the battery, only a fraction of which is recovered through regenerative braking—less than 25% in most real-life cases, to say nothing of friction losses tied to the car’s weight upon the tires.

Consider the comparably-sized Nissan Leaf and BMW i3 (the latter without the optional 647 cc “range extender” gas engine). While the Leaf weighs 3,291 lb (1,493 kg), the carbon-fiber i3 is 20% lighter at 2,635 lb (1,195 kg). This means the i3 can use a smaller battery (22 vs 24 kilowatt hours) without sacrificing performance: Both cars claim a driving range of 80-100 miles.

No surprise, then, that Apple seems interested in the carbon-fiber manufacturing process BMW developed for the i3. (Selected videos here.) But can Apple score points on mass/range against a very determined Bavarian competitor who recently announced that 100% of its fleet will be electric within a decade? (Though, as many have pointed out, “electric” doesn’t mean “all-electric”.)

Speaking of batteries, the situation is similar. There’s little hope of Apple designing its own battery (no Moore’s Law for batteries—electrochemistry is still science, not technology), so gaining a significant advantage, even with a supplier lock-in, is unlikely. In some ways, batteries are comparable to Intel chips: Everyone gets the same level of performance.

Three: user interface

The user interface (UI) in most vehicles today remains laughably complicated, even as recent research shows consumers value in-car technology more than driving performance.

An Apple Car UI could easily score points compared to Ford’s Sync UI or GM’s (recently improved) Cue, starting with seamless integration with passenger devices and services, and going as far as intelligent driving assistance technology regulations permit. (Consumer Reports has a full run-down on car infotainment systems.)

Apple’s advantage resides in understanding that it’s the how, not the what that matters—that making components work together is more important than simply offering a long list of stubbornly solitary features.

Four: distribution and service

The NY Times features a revealing story on US car dealers who steer buyers away from electric cars: “A Car Dealers Won’t Sell—It’s Electric.” Some of the examples in the article are striking, such as salespeople who refused to show a plug-in Prius that actually was in stock, and who denied that Ford made an electric Focus. The reason, according to the article [emphasis mine]:

Salespeople who have spent years understanding combustion cars don’t have time to learn about a technology that represents a fraction of overall sales, and the sales process takes more time because the technology is new, cutting into commissions.

I don’t buy this explanation. Go to any car dealership and you’ll see salespeople with plenty of time as they wait for prospects. I don’t blame them for not studying up on the latest technology—there’s no advantage: At most dealerships, the real source of profits are the maintenance contracts that are pushed on consumers, many of whom don’t realize that good modern cars need very little upkeep. For such dealers and commissioned salespeople, the electric car is the enemy: ”There’s nothing much to go wrong,” [Nissan’s Marc] Deutsch said of electric cars. “There’s no transmission to go bad.” As the Nissan website states: “Say goodbye to pricey oil changes and tune-ups. With fewer moving parts than any car you’ve ever owned, the Nissan LEAF is ultra low maintenance.”

In great car dealer tradition, this didn’t stop a salesperson from offering “the works” to the buyer of an electric VW Golf: “[…] a $15-per-month maintenance package that included service for oil changes, belt repair and water pumps.”

For Apple, this is an opportunity to offer a pleasantly simple buying experience. Apple could offer simple lease terms—not unlike the deal you can get today for an iPhone—without taking the customer through the wringer in the finance manager’s office.

It sounds good until one asks: where? Most Apple Stores don’t have the facilities to show a car and provide a test-drive, let alone perform oil changes—sorry—“basic maintenance.”

But…what maintenance operations? There’s no oil, no water, no transmission fluid. You would get your tires changed, as you do today, at a specialty store. Most small operations, such as replacing wiper blades, could be performed at the customer’s home/office, with rare surgery at an Apple-certified shop. Actually, I wonder how often we go to a car maintenance place compared to the frequency of Apple Store visits.

Finally: charger stations

In the last 18 months, I’ve seen a large number of charging stations appear in and around office buildings…and not just “culturally forward” enterprises like Google, Facebook, and Apple. Even law firms now offer charging posts (for pay, of course); so do parking garages. In some municipalities, home building permits require wiring for an electric car charger. By the time the putative Apple Car comes out, finding a charger won’t be an issue.

I’ve avoided questions such as price, the scale of a roll-out (local, regional, nation-wide?), and many others concerns that lurk under the surface but that I can’t quite formulate to my satisfaction.

For example, are Apple’s 40% gross margin and +20% net income numbers eternal? If they are, we might not see an Apple Car. But if an aging personal computing industry causes Apple to reconsider its profit strategy as it enters its fifth decade (the company will be forty years old next year), attacking the venerable, lower-margin car industry might make sense.

There are sharp minds in Cupertino at work on the problem, and you can guess what I hope their answer will be. But there are no warranties expressed or implied: Exciting as they are, Apple Car rumors don’t obligate the company to a vehicle, in 2019, or at any other date.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.