Audio cassettes are back—because hipsters

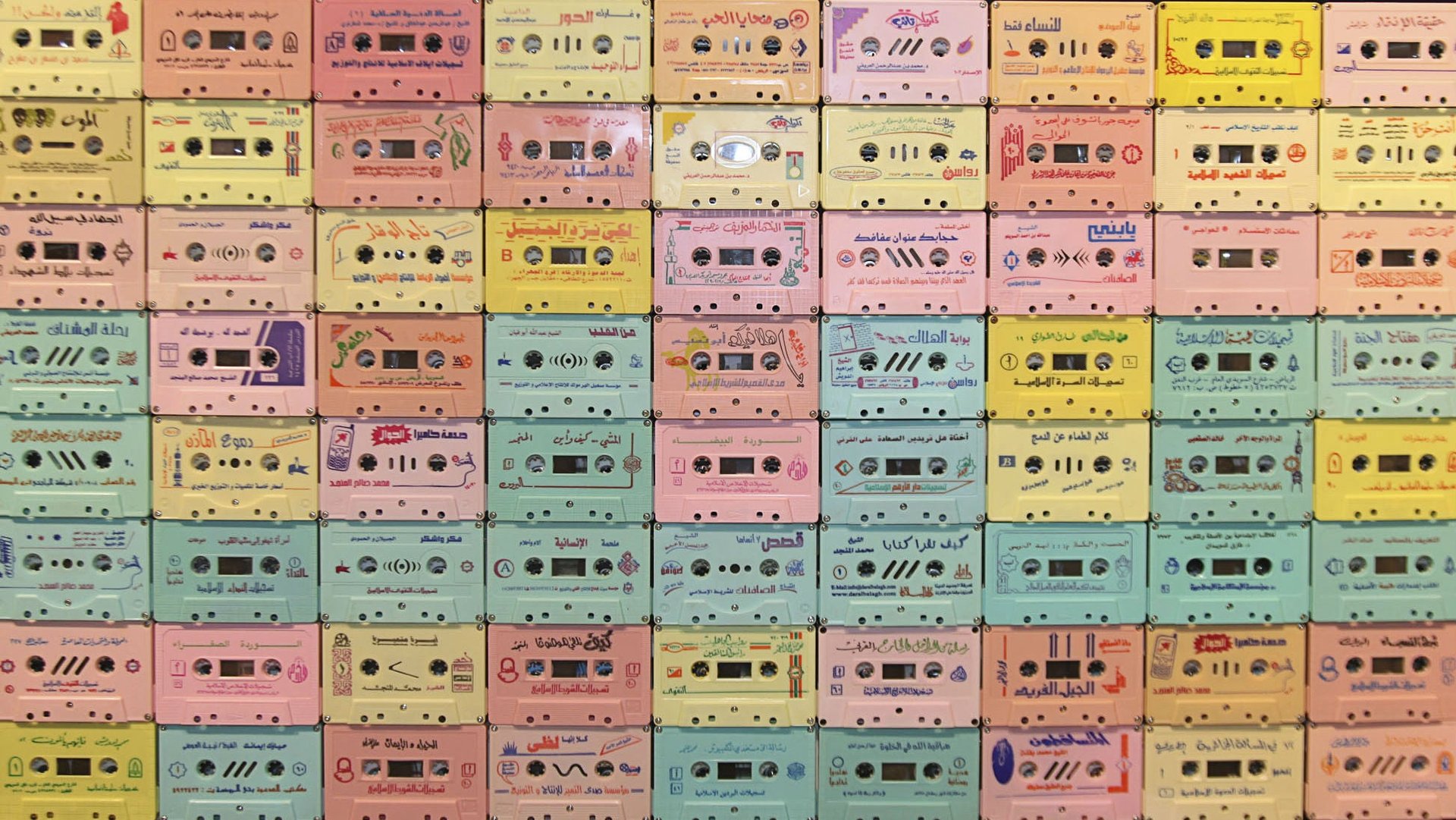

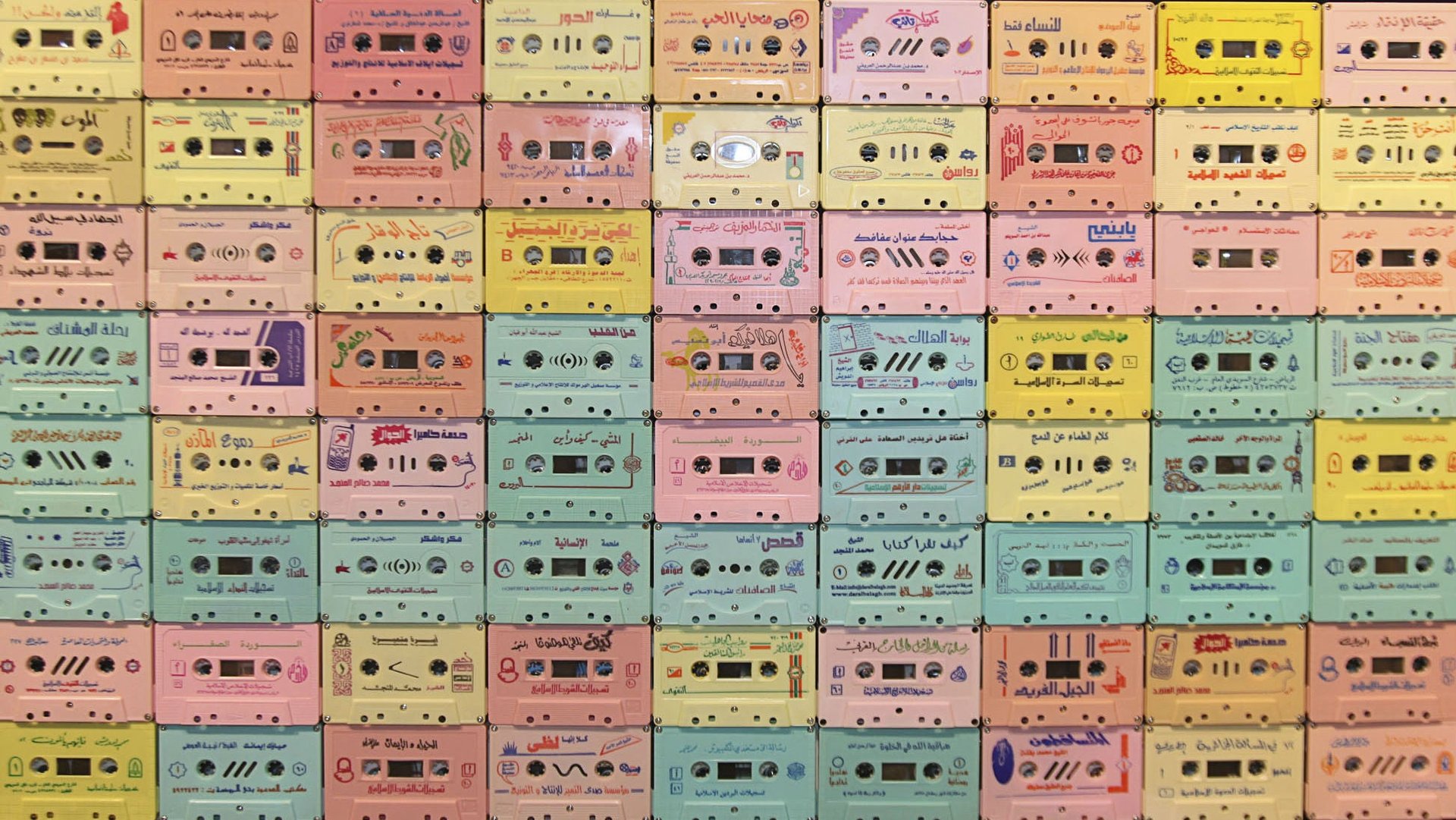

It’s one of the glorious, forgotten gestures of the 1990s: pressing the “play” and “record” buttons simultaneously, and then “stop” at the exact right time, to make a mixtape. And so is sticking a pen inside a cassette hole to rewire a tape gone awry. Much like vinyl, there is a romanticism to the experience of audio tapes that no CD—let alone MP3—can hope to replicate.

It’s one of the glorious, forgotten gestures of the 1990s: pressing the “play” and “record” buttons simultaneously, and then “stop” at the exact right time, to make a mixtape. And so is sticking a pen inside a cassette hole to rewire a tape gone awry. Much like vinyl, there is a romanticism to the experience of audio tapes that no CD—let alone MP3—can hope to replicate.

Now, 20 years after they were made nearly obsolete by CDs, a new generation of listeners are falling for the discreet charm of audio cassettes.

Steve Stepp, owner of National Audio Company, says his company has about 95% of the US market. Unlike records, it’s not a higher quality of sound that attracts listeners to tape, but rather what Jackson Miller, a buyer at independent music store and New York City concert venue Rough Trade, calls “lifestyle branding.” What matters to the listener is the way a tape forces a different experience (you can’t skip tracks, for instance), and the nostalgia, channeled by a sound different (in a way, of lower fidelity) from the digitally mastered quality of CDs.

National Audio Company has been in business since 1969, when Stepp founded it with his father in Springfield, Missouri. For years, the popularity of cassettes kept growing, till it peaked in 1989, when the US market alone counted 450 million albums sold in cassettes. As Stepp told Quartz, “the market was amazing, you could sell cassettes as fast as you could make them.”

With the arrival of CDs, however, the decline of tapes was sudden. In less than a decade, the market for cassettes essentially disappeared—to they point that the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) stopped tracking cassettes sales. National Audio Company’s competitors closed or turned to CD production in the 1990s, and as they did Stepp—whose company stayed in business thanks to educational and religious tapes—bought their equipment.

For years, music tapes were relegated to experimental home recording, until what Stepp calls “the retro revolution” happened around 2006. A renewed interest amongst under-35-year-olds generated new growth for the business, and with essentially no competitors left in the US, National Audio Company is registering a golden age of sorts. According to Stepp, the company has registered 20% year-over-year sales growth from 2006 to 2012, and an estimated 31% growth from 2014 to 2015, when its global sales reached 20 million units. Stepp says he can barely keep up with hires, or with the raw material supply. “We anticipated the return of analog music, we just didn’t expect it so fast,” Stepp told Quartz.

Tapes are cheap to produce—about $2 per piece for the final product—and in the mid-2000s, according to Stepp, independent bands started releasing small tape runs—100 to 1,000. This might be as much a marketing move as the genuine desire to test the quality of sound on different media. While they were out of the mainstream market, Miller told Quartz, tapes have been used to record avant-garde, experimental music. Because of that history, recording a cassette lends a band some level of “indie” credibility.

“For some people, listening to [an] analog tape might be pleasing,” Greg Tiefenbrun, who runs a post-production facility and has been a DJ for many years, told Quartz. He thinks, however, it’s not a matter of quality: “I don’t think you can say ‘this sounds better or warmer.’ Each piece of recording sounds different,” he said.

Independent artists have started the trend, but major labels have caught on. Canadian singer Nelly Furtado recently released a collaboration album only on tape, and Stepp says his company has produced tapes for Universal Music and Sony, including the famed Guardian of The Galaxy soundtrack cassette in 2014.

According to data from Nielsen Music, there has indeed been a near 30% increase of sales in the US from 2014 and 2015, though the volumes reported are very small: only 0.2% to 0.3% of album sales in the US have been tapes in the past three years, for a total of 50,000 to 64,000 units a year. This means that the growth is not yet relevant enough to affect the big distribution, which is what Nielsen tracks.

This would be in line with the idea that the resurgence in cassettes is driven by nostalgia. ”The value is aesthetic,” DeVon Harris, a Grammy awarded music producer, told Quartz. “It’s ironic and iconic that someone has a cassette tape,” he explained, likening the newfound popularity of cassettes to what happened with the comeback of vinyl records (which are bought more than listened to).

Stepp doesn’t appear to think this is a fad. “I think the future is very bright for the audio cassettes,” he told Quartz, because the people buying them “have listened to digital music but prefer analogue.”