The sweet story behind Peanuts’ groundbreaking first black character

When Charlie Brown first met Franklin, not everyone was pleased.

When Charlie Brown first met Franklin, not everyone was pleased.

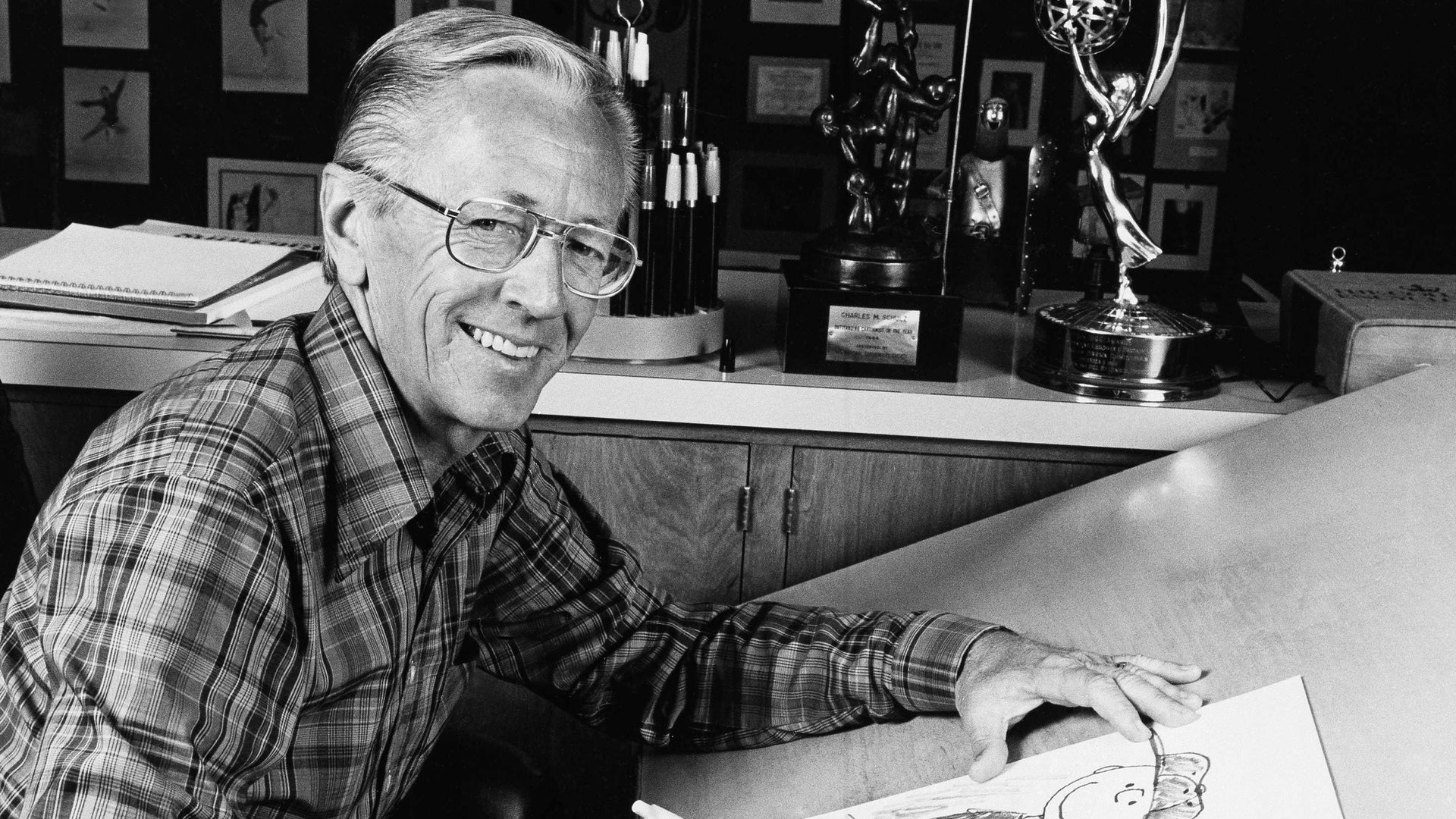

Only months before illustrator Charles M. Schulz introduced the first black character into his massively popular comic Peanuts, US civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated. It was 1968, and the United States was facing a crucial test of its ability to integrate.

About a decade prior, federal troops had escorted a small group of black students to meet their white classmates in a school in Little Rock, Arkansas. When Franklin was first shown with his white peers, some comic strip readers reacted badly to the new character.

But one reader was ecstatic: Harriet Glickman, a Los Angeles-based mother of three.

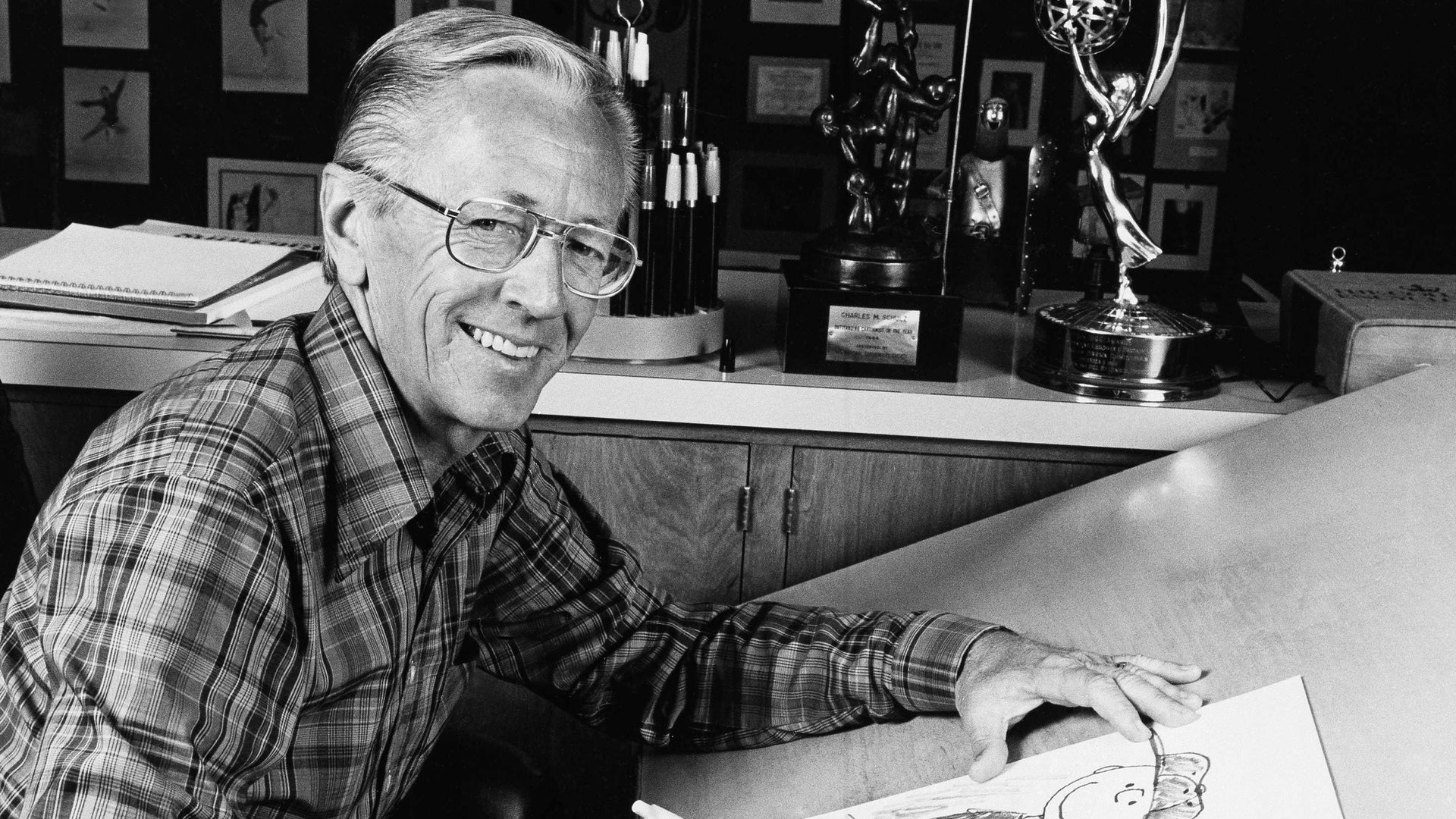

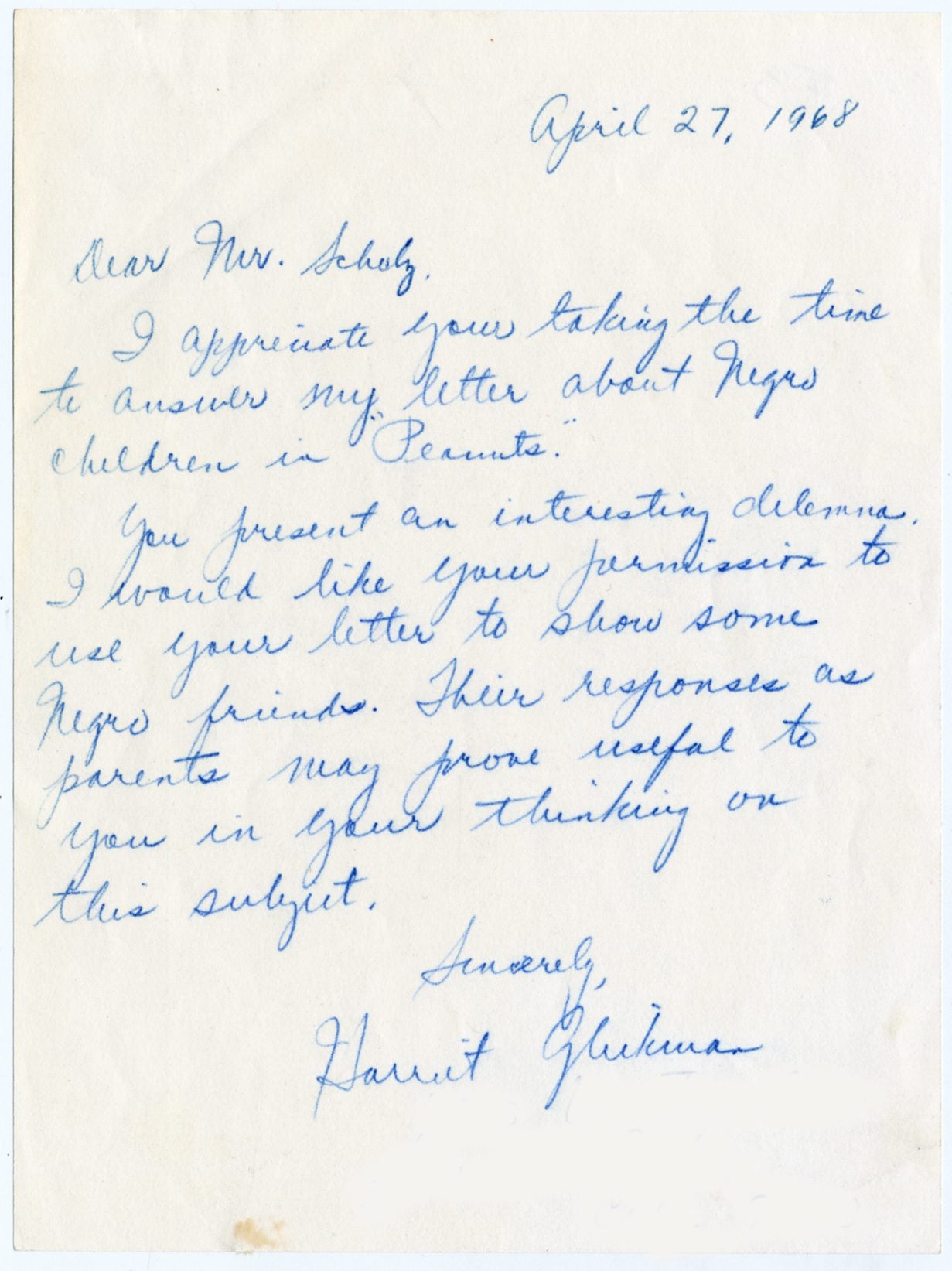

In April that year, she had written to Schulz:

“Since the death of Martin Luther King, I’ve been asking myself what I can do to help change those conditions in our society which led to the assassination and which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate and violence.”

She asked for the “introduction of Negro children” into the Peanuts world, appealing to its reputation:

“I’m sure one doesn’t make radical changes in so important an institution without a lot of shock waves from syndicates, clients, etc. You have, however, a stature and reputation which can withstand a great deal.”

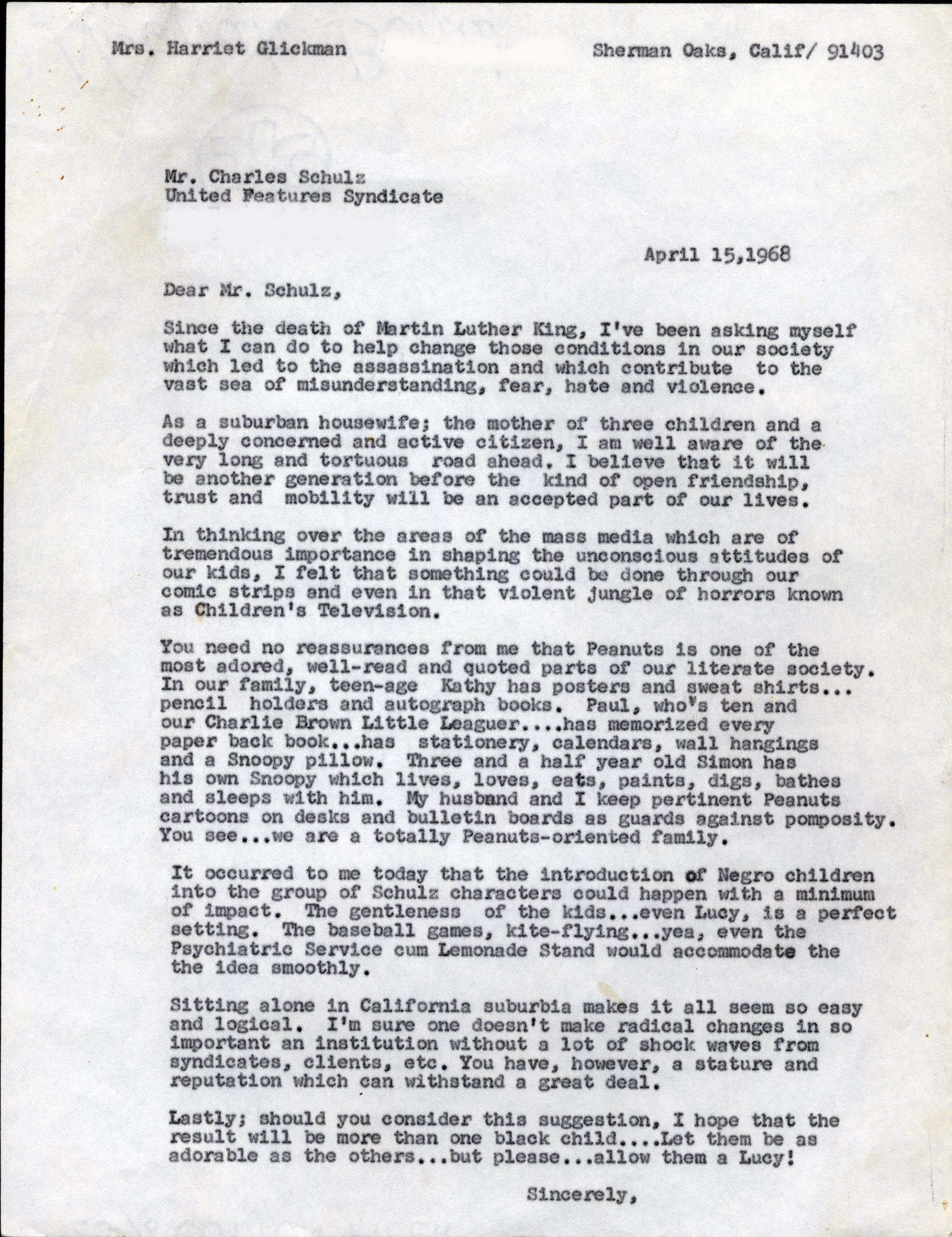

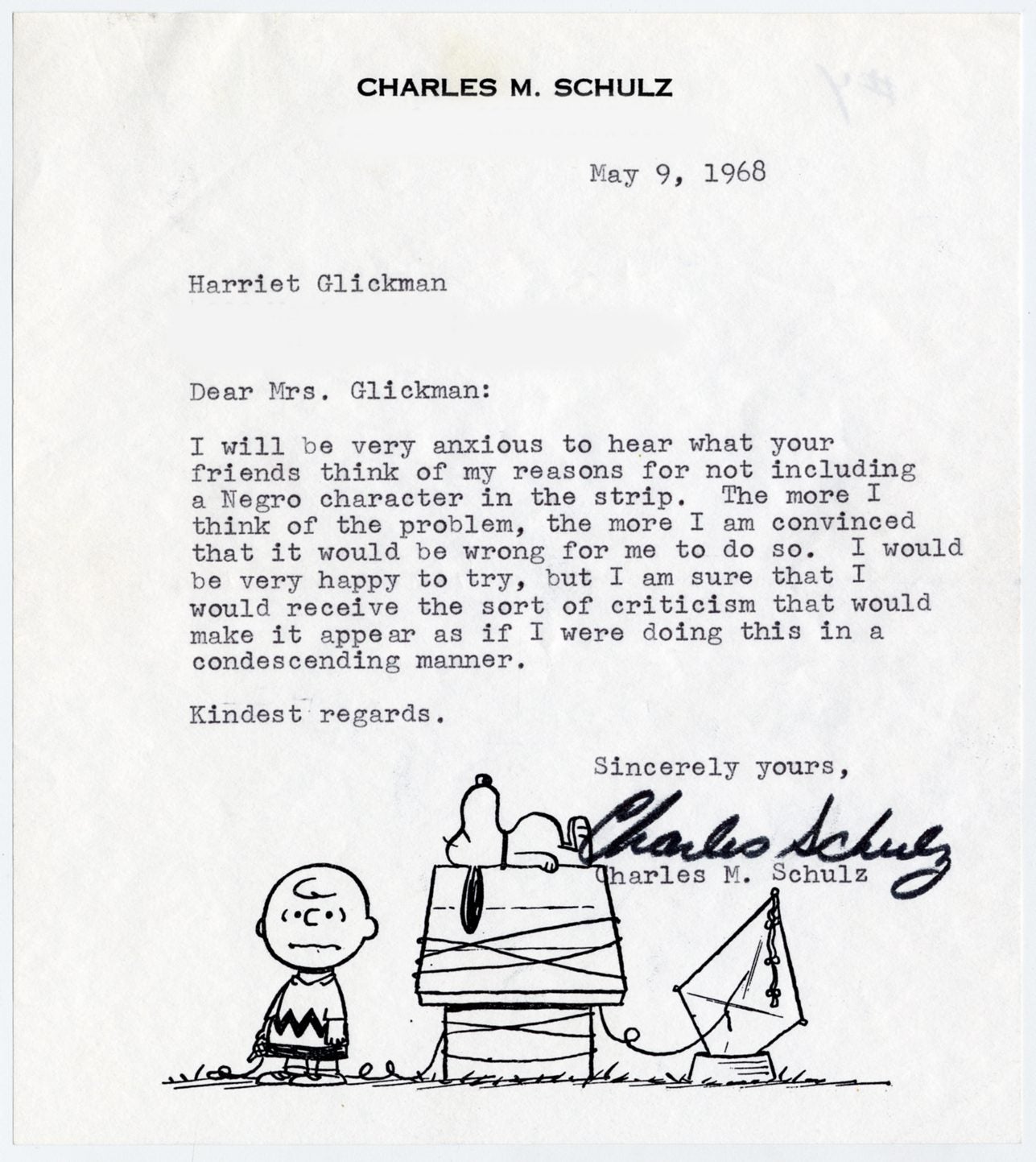

Schulz quickly wrote back. He was enthusiastic, but worried the move would appear patronizing to his black peers.

An exchange continued between the two, in which Glickman offered to speak with black parents she knew to get their thoughts.

At last, Schulz wrote on July 1 that Glickman could expect see a new character in the strip later that month.

Franklin debuted in the July 31 strip as a boy Charlie Brown met on the beach. As Corry Kanzenberg, the curator of the Schulz Museum, tells Quartz, it was very unusual for the cartoonist, who prided himself on being the sole creator behind Peanuts, to base such a decision on a fan’s suggestion.

Franklin has been noted as far less anxious than the other characters. He is the kindest to Charlie, never criticizing or mocking him. (Some have argued that the blandness of Franklin’s character is indeed patronizing.) In the strip, he attends school with his white friends, Marcie and Peppermint Patty.

Glickman tells Quartz that she had no idea what kind of impact she would make with her letter to Schulz. But after King’s death, she says, “You wanted to do something: you felt powerless in a situation like that. I thought, ‘This might be a nice little idea.'”