The Fed just raised rates for the first time since 2006

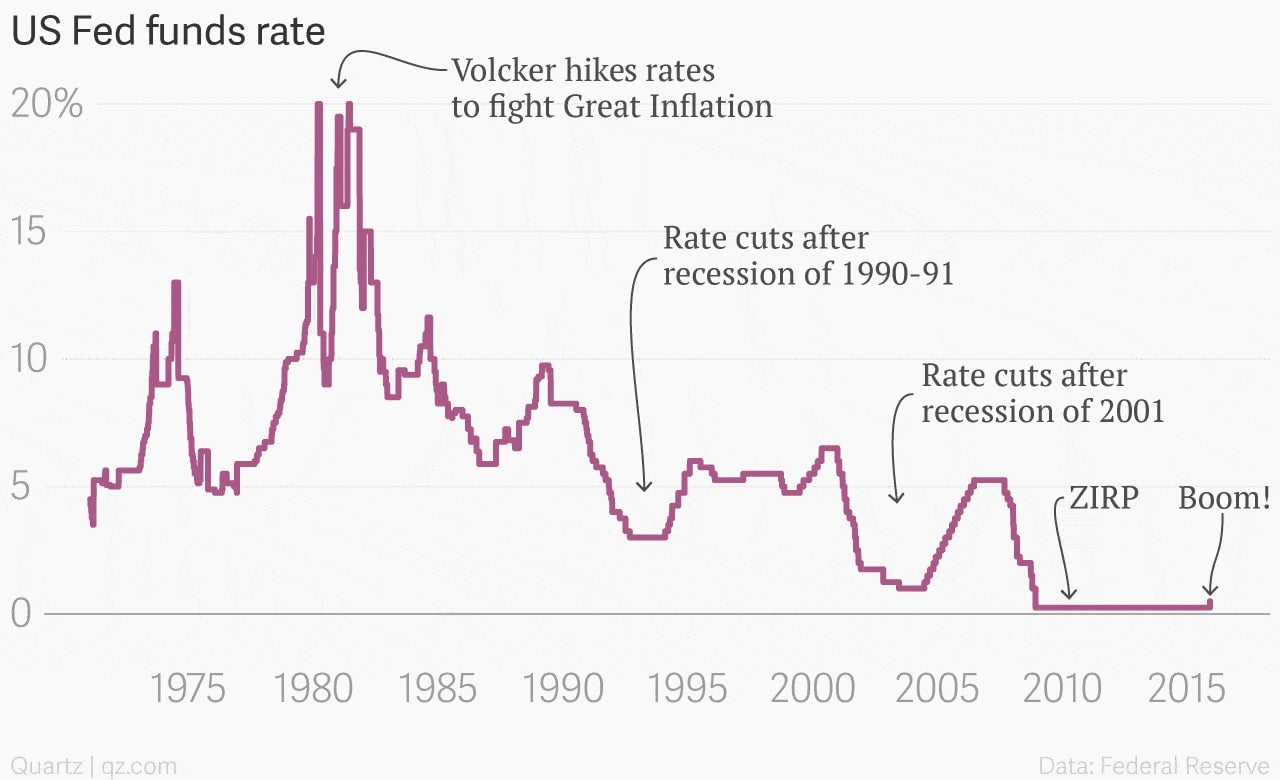

An almost biblical seven-year stretch of near zero interest rates effectively ended Wednesday when the Federal Reserve announced that it would increase its benchmark monetary policy rate a quarter of a percent.

An almost biblical seven-year stretch of near zero interest rates effectively ended Wednesday when the Federal Reserve announced that it would increase its benchmark monetary policy rate a quarter of a percent.

The decision came exactly seven years after the Fed cut the target for its benchmark Fed funds rate to near zero on Dec. 16, 2008, an extraordinary step prompted by the worst financial crisis since the wave of bank failures that struck the US economy during the Great Depression.

The end of the Fed’s “zero interest rate policy”—dubbed ZIRP by observers—reflects substantial improvement in the US economy since darkest moments of the Great Recession and the painfully slow recovery that followed.

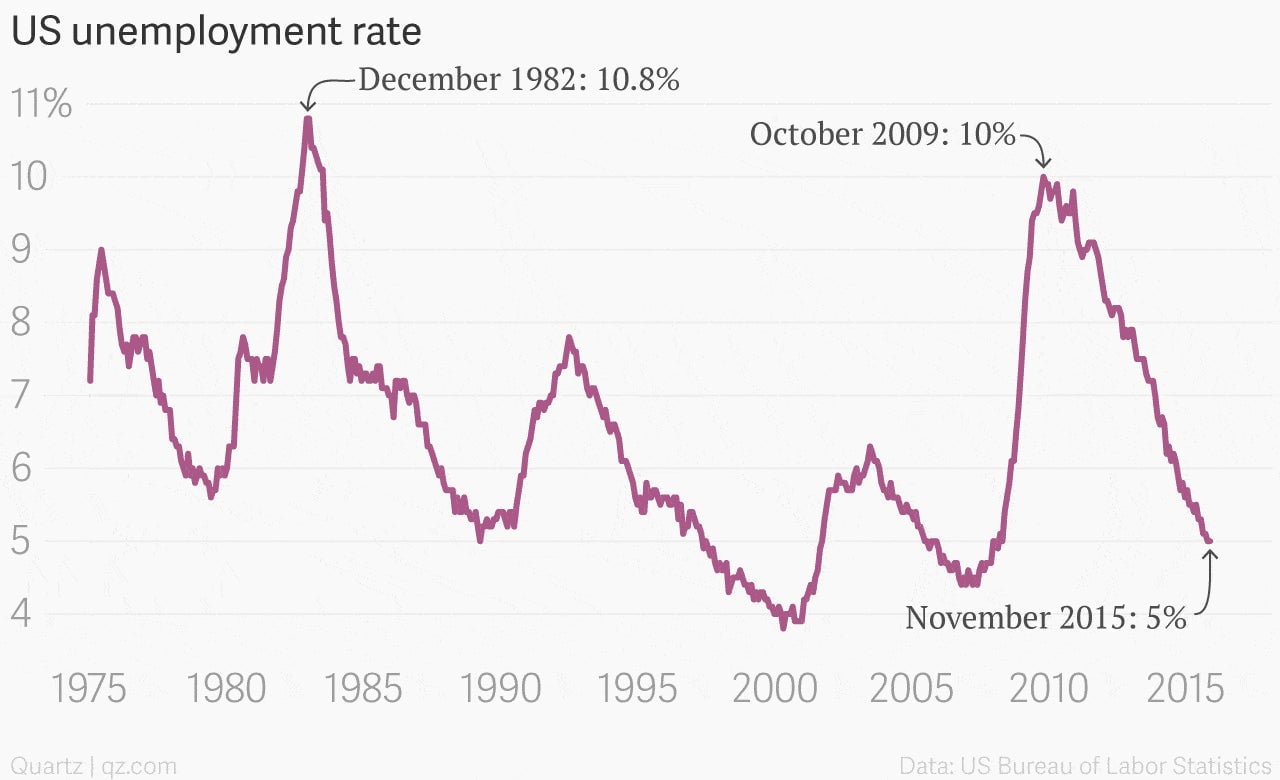

Most notably, the US unemployment rate has fallen from a Great Recession peak of 10% in October 2009 to 5% in the most-recent update on the US labor market.

But while the decision to lift the Fed funds rate marks an important step away from crisis-era policies aimed at supporting the economy at all costs, the path forward for the Fed—and the US economy as a whole—remains uncertain.

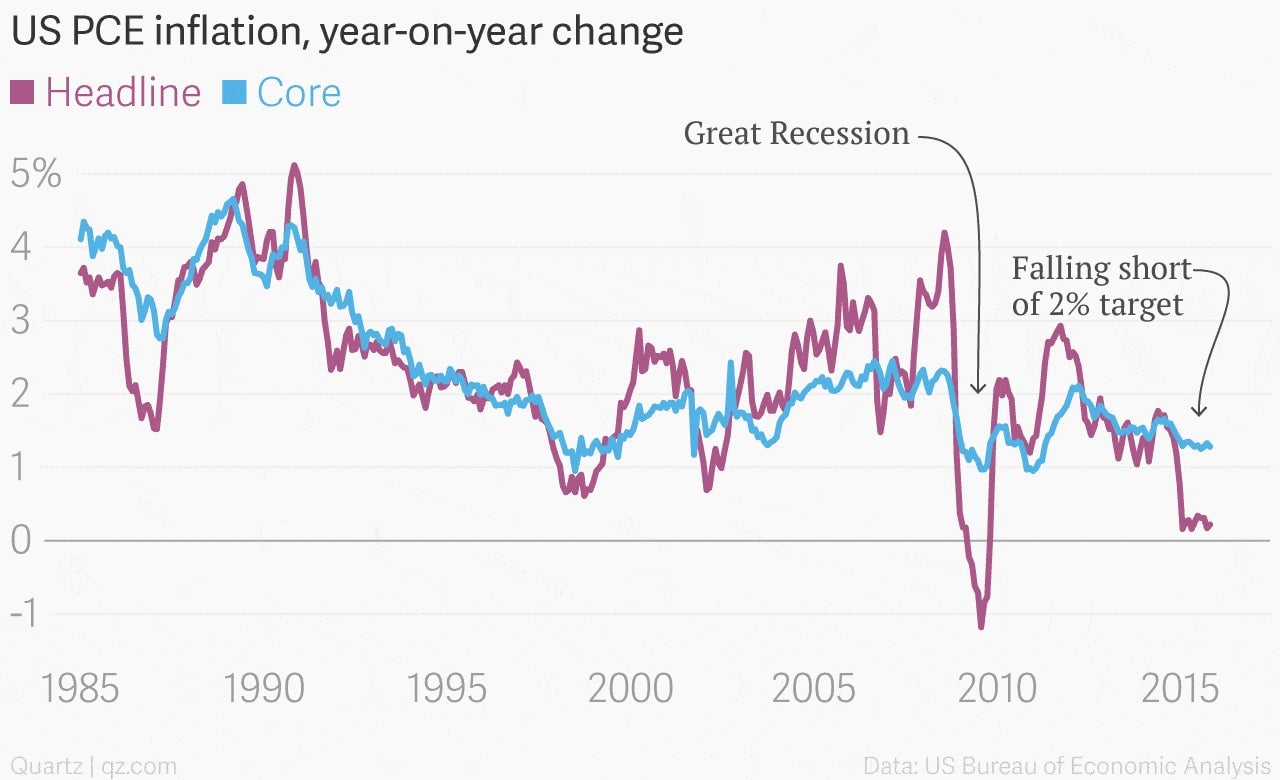

For one thing, the Fed continues to fall short of its own goal of generating an inflation rate of roughly 2% a year for its preferred gauge of price increases—the price index for personal consumption expenditures, excluding food and energy prices. (This is what’s known as “core” PCE inflation.)

While rising prices—inflation—might not sound good to consumers, economists believe a low, stable rate of inflation has significant economic benefits. Inflation helps make debts easier to pay over time and should the economy run into rocks, a bit of inflation serves as a cushion to keep the economy from falling into outright deflation.

Deflation, a broad-based decline in price levels, is much more worrisome for central bankers, as it disincentivizes spending—why buy now if prices will be lower later?—and investment, as it makes debts much more onerous to pay off.

The fact that the Fed raised rates in the face of persistently low inflation suggests policy makers there believe weakness is largely due to the sharp fall in oil prices over the last year. All the same, members of the Fed’s monetary policy committee, the FOMC, will be anxiously looking for US inflation rates to rise over the coming months.

Higher inflation would reassure them that they didn’t pull away support from the economy too quickly, which has been the error policy makers have committed in the past when grappling with the aftermath of long periods of sluggishness and low inflation that tend to follow a deep recession brought on by a financial crisis.

For instance, in 1937 a relatively small tightening in US monetary policy—coupled with a sharp fiscal contraction—helped tip a recovering US back into the the Great Depression. (The episode came to be known the Mistake of ’37.)

In the 1990s, Japan made a similar error by raising its consumption tax in 1997, after years of trying to stoke economic recovery following a real-estate bust that turned into a banking bust, which turned into a deep recession. Tighter policy—along with the Asian financial crisis—helped send Japan’s economy back into the dumps.

Past isn’t necessarily prologue, of course. On the other hand, it might be. The bottom line is that the Fed has made its move, and it’ll be a while before we know whether it was the right one.