At 4.40pm on the 12th of January, 1970, the Nigerian Civil War came to a formal end with a radio broadcast from Lt. Col Philip Effiong, commander of the army that for the previous thirty months had been fighting for secession from Nigeria—and the creation of an independent Republic known as Biafra.

“I am convinced that the suffering of our people must be brought to an immediate end. Our people are now disillusioned, and those elements of the old government regime who have made negotiations and reconciliation impossible have voluntarily removed themselves from our midst,” announced Effiong, who had recently taken over the leadership of the rebel forces. Lt. Col Odumegwu Ojukwu, the Biafran head of state, had fled to exile in Cote d’Ivoire.

In that moment, the bitter fighting, which had claimed the lives of between a million and three million people, ended. But in the hearts and minds of many, especially on the losing side, the war never really stopped, in spite of a determined push by the federal government to advance a ‘no victor, no vanquished’ post-war agenda.

In the decades since the war ended resentment has simmered, rising to the surface in the wave of ethnic grievances and frustrations that accompanied the return of democracy in 1999. The Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) emerged, alongside similar groups in other parts of the country: the O’odua Peoples Congress (OPC) in the southwest (dominated by ethnic Yorubas); the Arewa Peoples Congress (APC) in the north, and the Egbesu Boys of Africa (EBA) in the Niger delta. “The surge in militias ironically appears to be what unifies Nigerians against the excesses of the state after thirty years of deleterious military rule,” noted Nigerian academic Osita Agbu in a 2004 essay.

The Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB) movement has now replaced MASSOB in the national consciousness. IPOB, headquartered in Spain, was recently founded by Nnamdi Kanu, a Nigerian emigrant to the UK, known by his followers as ‘Director’. It is an incredibly media-savvy organisation, operating or affiliated with an active diplomatic arm (Biafra Diplomatic Mission Worldwide), online TV (Biafra Television) and radio (Radio Biafra) stations (which the Nigerian government has unsuccessfully tried to silence, an online newspaper (Biafra Times), and active social media outlets (including a Facebook page with 223,000 Likes).

In February Kanu opened an “Embassy” of the Republic of Biafra in Spain; IPOB claims to have members in more than eighty countries. Kanu was arrested by state security services in Lagos in October 2015, and has been in detention since then even after a Federal Court ruling on Dec. 16 deemed the activist’s detention unlawful. Since then IPOB has regularly held street protests, calling for his release. Several people have been reported killed in clashes with the police and military.

The goal of IPOB is a clear one: the “restoration” of Biafra. Presenters and callers on Biafra’s television and radio stations commonly speak of “servitude” and “self-emancipation”, and of the millions who died during the Civil War. One recent caller, from Sweden, called for “total liberation from that entity called Nigeria”, adding that “the ball is in our court now, the earlier we start preparing the better.”

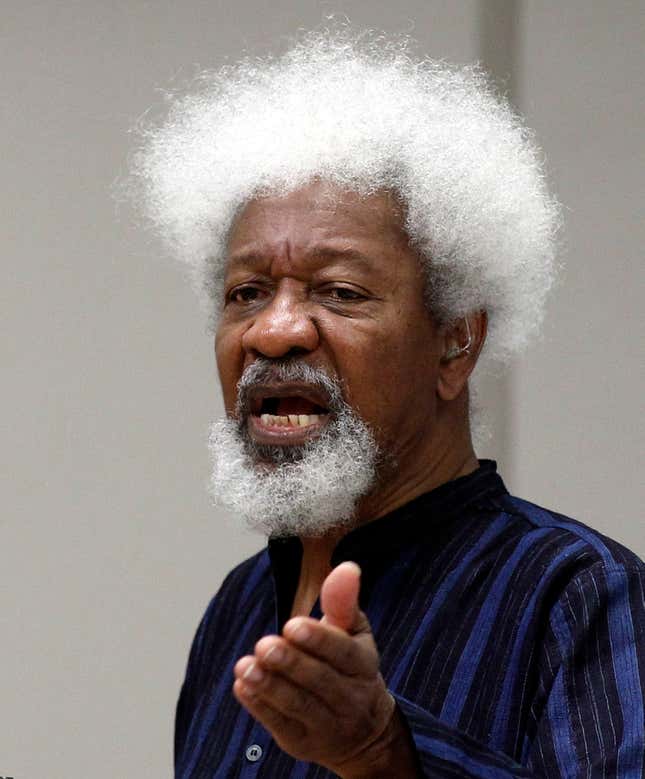

The most important question at this time is: what should Nigeria do in response to the agitation for Biafra. Perhaps the way to look at this question, is by focusing first on what Nigeria should not be doing. Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka—jailed for almost two years during the war by the Nigerian government, on allegations of spying for the Biafrans—said in a recent interview: “During the (civil) war I said at that time that Biafra cannot be defeated. People misunderstood what I was saying. I said once an idea has taken hold, you cannot destroy that idea. You may destroy the people that carry the idea on the battlefield, but, ultimately, it is not the end of the story.”

Underlying issues

And this is the premise from which the Nigerian government ought to be acting; that there are underlying issues to the Biafran agitation that need to be addressed. IPOB draws its members and sympathisers from the teeming ranks of young ethnic Igbos within and outside the country. Fuelling the disenchantment is the obvious, longstanding neglect of a region that has long proved itself an enterprising and inventive one. With enough electricity, and better transport connections, cities like Aba and Nnewi would soon rival Shanghai and Guangzhou in manufacturing output.

Hampered by infrastructure problems and government neglect, they are a shadow of what they could easily be. Large armies of youth, who should otherwise be gainfully employed, are therefore idle. (This is of course not peculiar to the region, it is a familiar tale across Nigeria).

It goes beyond joblessness and poverty. The battle is as much ideological as it is economic; there’s a practised propaganda machine that the Nigerian government has yet found no answers for. The original Biafra was famously adept at spin, hiring a small but supremely effective Geneva-based American PR firm to support what famous intellectuals like Chinua Achebe were doing as ambassadors and spokesmen for the cause. The battle for the hearts and minds of the susceptible is the hardest war to fight, as we’ve learnt from recent dealings with Boko Haram.

The Nigerian government would do well to pay attention to Soyinka’s advice: “Ask what are those things we can do to make you content, to make you feel part of this entity (Nigeria)… what can we do to make them feel that they belong and are not alienated. Listen to some other Biafrans and ask them why they want to stay. But, don’t go around saying ‘the sovereignty of this country is indivisible, this won’t happen under my watch, it is not negotiable’. That type of language would only make matters worse.”

In other words, a belligerent response invoking the unquestionable ‘unity’ of Nigeria—the default response of the generation of Nigerians who fought for Nigeria during the civil war—would only make things worse, not better. The starting point for the Biafra response ought to be the acknowledgement, as Matthew Hassan Kukah, Catholic Bishop of Sokoto, recently said: “The Movement for the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) has the right to seek Biafra, since we have freedom of expression. It would also make sense for the government to immediately release Mr. Kanu from detention, even if conditionally.”

January next year will mark 50 years since the coup that triggered Nigeria’s slow but steady descent into the war. It would be a good time to remind the world of what Ojukwu said, years after the war: “I led proudly the first one, I don’t think a second one is necessary. We should have learnt from that first one, otherwise the dead would have been to no avail, it would all have been in vain.”

Buhari’s symbolic gesture

A special commemoration by president Buhari—who, as a young army officer fought in the civil war on the side of Nigeria—would be a powerful symbolic gesture. A special ceremony—in Enugu, the initial capital of Biafra, or other prominent eastern cities, should bring together prominent surviving actors and combatants from both sides. Mistakes and war crimes must be acknowledged, and forgiveness sought. This should be combined with a commitment to developing the region: completing a second, toll-free bridge over the Niger, fixing the region’s notorious highways (a problem Vice President Yemi Osinbajo recently acknowledged), and upgrading the railway network that links the landlocked region to Port Harcourt, would be game-changing moves, in my opinion.

And of course there’s always the final option of a referendum, in the manner of South Sudan and Scotland. The prospects of a Biafran success in a referendum would to a large extent turn on the willingness of the oil-rich Niger delta to go along with the new country.

Considering a legacy of historical tensions between the majority Igbo and the minority non-Igbo of the region, will the non-Igbo who dominate the delta, and who recently produced Nigeria’s first elected minority president in Goodluck Jonathan be enthusiastic about exchanging a difficult minority relationship with Nigeria for a difficult minority relationship with Biafra? Without the delta, Biafra would be, like South Sudan, a landlocked country dependent on a not-very-friendly neighbour for its energy requirements; a prospect that doesn’t seem very encouraging.

While the approach outlined above might appease moderates within IPOB, it looks unlikely to calm the radicals, like Kanu, who insist on establishing Biafra at all costs. On May 30, 2014, at an event to commemorate the 1967 declaration of the Republic of Biafra, Kanu reportedly said: “There is no going back, by December 2015, Nigeria would have seized to exist; we shall fight until we get Biafra, if they don’t give us Biafra, no human being will remain alive in Nigeria by that time; we shall turn everybody into corpses; you better go and buy your coffin.”

While the debate continues on what Nigeria should be doing; what it cannot afford to do is the very thing it has always done: act like this will be a self-resolving crisis, or one that a military clampdown will settle. The story of the unchecked rise of Boko Haram offers a cautionary tale, even as the rhetoric of IPOB grows increasingly militant.

The radicalisation of Boko Haram to the level with which we associate them took place in 2009, when the sect founder and leader Mohammed Yusuf was murdered in yet unclear circumstances in police custody, shortly after he was handed over to the police by the military officers who arrested him. In the years that followed that injustice was one of the issues that the leadership of Boko Haram appeared fixated upon. Nigeria, in believing that there is a military solution to all expressions of ethnic and religious discontent, appears to have learned no lessons.