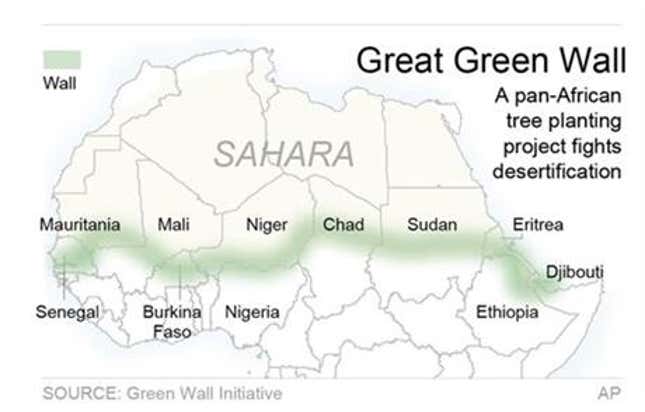

Eleven African countries are moving ahead with an ambitious pan-African effort in the Sahel-Saharan region of the continent to protect arable land from the encroaching Sahara desert—by planting trees.

The countries—Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Senegal—came together in 2007 to execute the $2 billion dollar project to arrest the creeping desertification in the region. The 15 kilometers (9 miles) wide and 7,775 kilometers (4,831 miles) long tree wall will stretch all the way from Senegal in west Africa to Djibouti in the east.

Desertification is a growing problem in sub-Saharan Africa. Estimates suggest that 40% of the region’s land has been impacted, exposing over 500 million people to devastating shifts in their environment and general livelihoods. These have included land erosion and decreasing rains that have subsequently crippled agriculture, exposed communities to health risks that come with increasing sandstorms and food shortages. The resulting insecurity has also contributed to the rise in extremism in parts of West Africa, some analysts contend.

The original idea for the tree wall was first proposed by former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo in 2005 and the African Union took it up in 2007. The World Bank helped co-finance it and the UN has been a supporter. At the recently concluded climate change summit in Paris, French president François Hollande promised that his government will offer up to €1 billion a year by 2020 to the anti-desertification effort, including the Green Wall project.

The biggest champion of the project has been Senegal. The west African country has thus far been able to plant over 12 million trees traveling up 150 kilometers and covering 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) worth of land. Eventually, this is meant to extend to 545 kilometers enveloping 800,000 hectares, Senegalese authorities told the Associated Press.

These efforts have helped to reverse some of the effects of years of land degradation. As a result, agriculture, once again, is becoming an economic activity for communities worse hit by the changes instead of forcing them into becoming nomads.

“Agriculture is easier for us,” one resident in northern Senegal told AP. “With livestock, the herd can die at any moment, and you are then condemned to live as a nomad. Here, with agriculture, we don’t need to move.”