See the havoc the payroll tax hike is unleashing on Americans’ paychecks

With January’s US personal spending and income data in, we’re really starting see how the expiration of the payroll tax holiday—also known as the payroll tax hike—is cutting into American incomes. (They were agreed to as part of the “fiscal cliff” deal.) US incomes fell 3.6% in January, the most in two decades.

With January’s US personal spending and income data in, we’re really starting see how the expiration of the payroll tax holiday—also known as the payroll tax hike—is cutting into American incomes. (They were agreed to as part of the “fiscal cliff” deal.) US incomes fell 3.6% in January, the most in two decades.

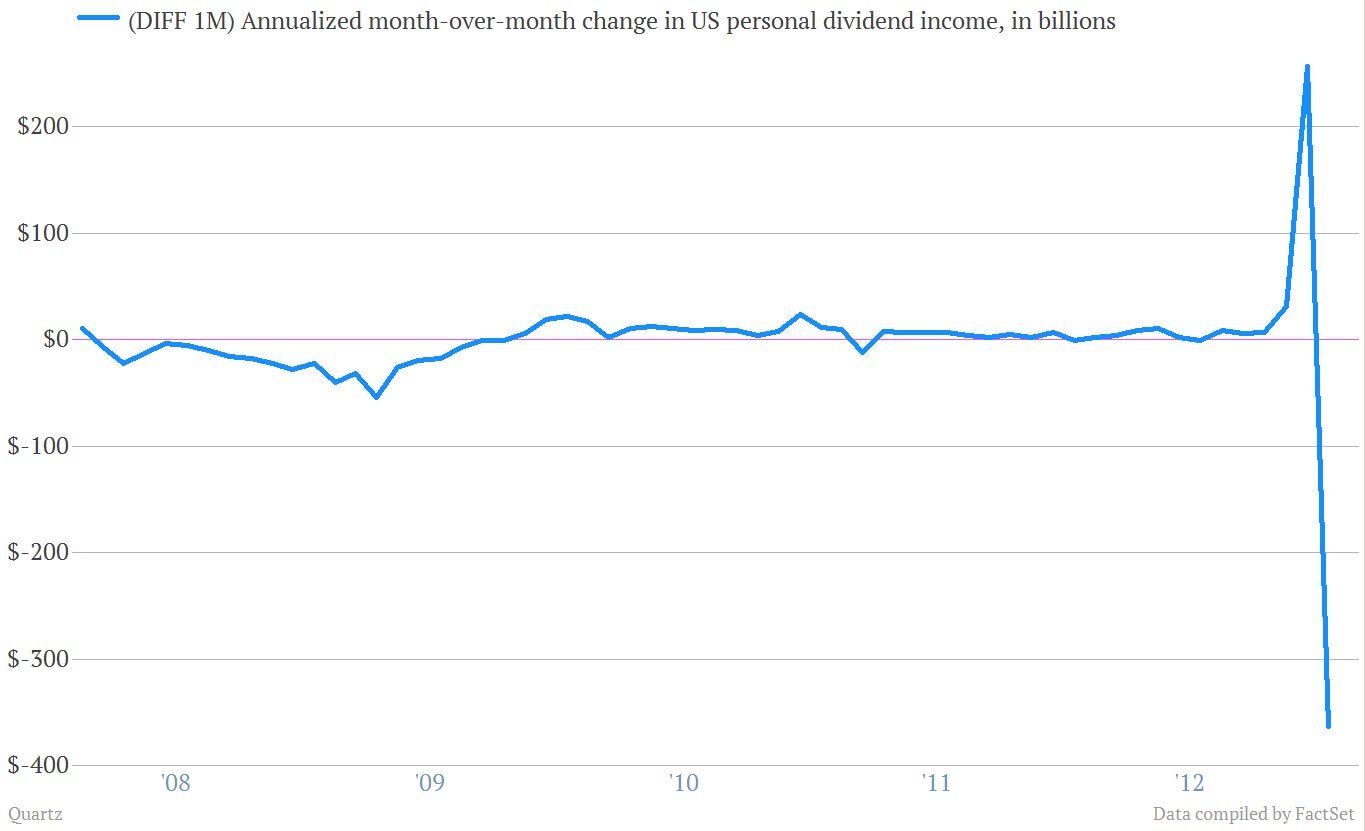

Corporate America rushed billions in special dividends out the door in December to beat the January deadline for the new taxes. Then, in January, dividend payments collapsed. (Remember, they were already paid in December.) And because this is a month-over-month change it looks especially bad.

Also the government sharply marked up the amount of cash taken from US paychecks as contributions for government insurance programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

As is their wont, government number-crunchers crammed a forecast for the increase in the entire year’s contributions into the January numbers. So this doesn’t mean that $127 billion was sucked out of American paychecks in January. It’s more of a guess about the increase in contributions over the entire year. Still, this “theoretical” number was a big part of the reason why US income numbers saw their sharpest one-month decline in 20 years. You can see there was a similarly sharp move lower—in terms of contributions—back in 2010, when the payroll tax holidays were put in place.

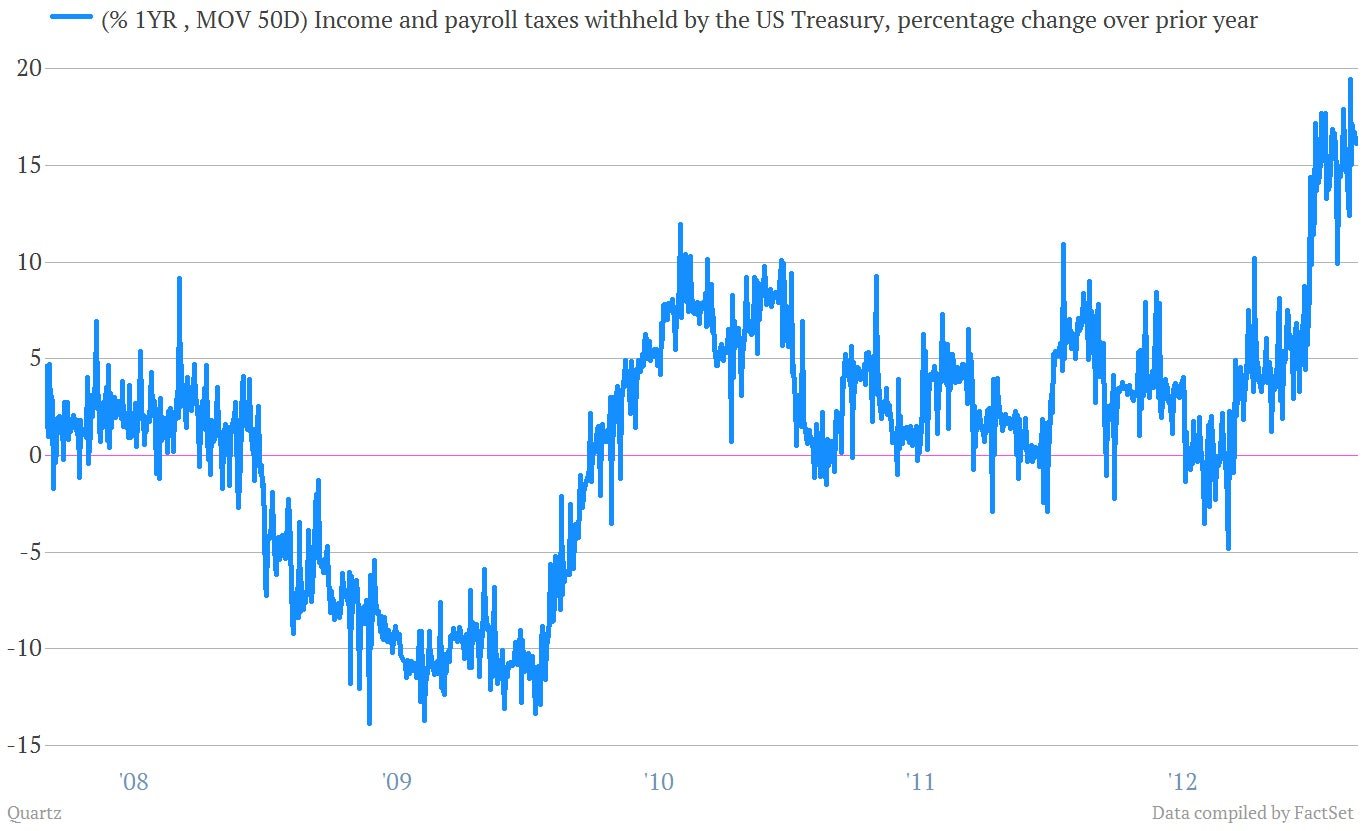

While that number may be “theoretical,” a lot more real cash from withheld income and payroll taxes is coming into the US Treasury.

Here’s a smoothed-out look at the daily tax witholdings deposited by US employers. (Because the numbers are so noisy, we put a 50-day moving average on them to clarify the trend.) It’s hard to say how much of the surge recently is related to the payroll tax hike, and how much is related to—say—increased increasing wages or job gains, which would also add to the total.

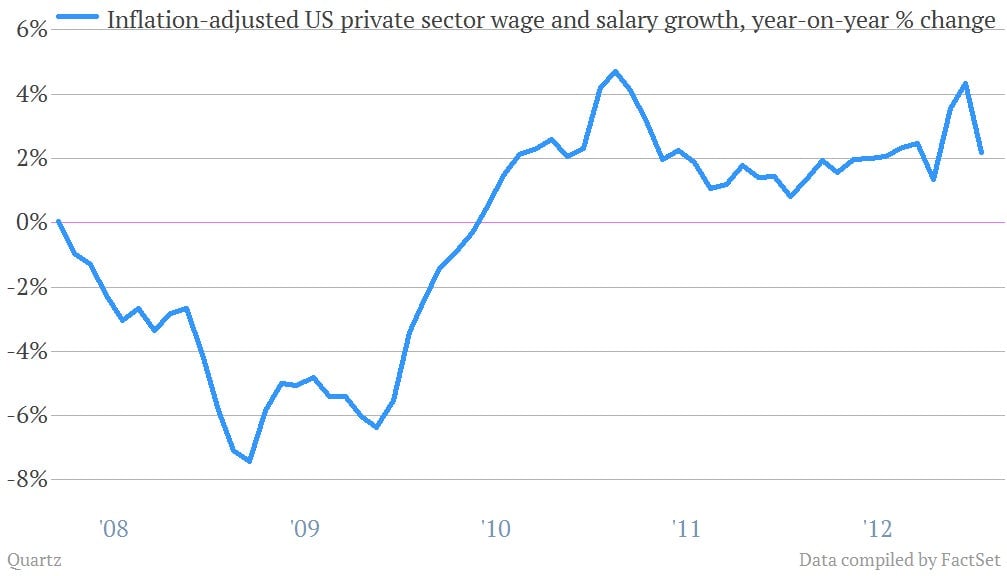

The good news, if there is any, out of the January pay report is that US wages and salaries look to be in better shape than they were last year. Compared to January 2012—and subtracting out the effects of inflation—wage and salary payments were up about 2.2%. That’s down slightly from December’s 4.3% gain. But the December bump was an outlier driven by some of the same dynamics that sent dividend payments up ahead of the tax January increases.

As always, there are caveats galore to consider. For one thing, the improvement in inflation-adjusted wage growth in the US has a lot to do with declining inflation, as well as increasing wages. And with the uptick in gas prices we’ve seen in recent months—New York gasoline futures are up 13% since the end of last year—inflation likely took a larger chunk out of consumer incomes in February and will also do so in March.

The point? While the US economy is benefitting from a considerable tailwind from the improvements in the housing market, US consumer finances are far from being rock solid. On the other hand, they haven’t been for decades.