There’s a nostalgia-driven underground market for hip-hop’s favorite Girbaud jeans

Girbaud Shuttle jeans weren’t just big, they were huge. The baggy, strappy denim was a wardrobe staple across the US in the early 2000s, and since then largely relegated to fashion’s dustbin.

Girbaud Shuttle jeans weren’t just big, they were huge. The baggy, strappy denim was a wardrobe staple across the US in the early 2000s, and since then largely relegated to fashion’s dustbin.

But in the last year and a half, Said Bsisso, a 24-year-old from San Francisco, has made a business of rescuing old pairs from thrift stores and online forums, taking them back to his San Francisco workshop, and tailoring them to a slim fit. After he’s done he charges his customers $350 for the trouble—triple their original retail price.

Bsisso and others like him exist in a parallel universe where they’ve been able to build a profitable cult following on a brand that was once one of hip-hop’s favorites. But the company itself has struggled to catch that wave, highlighting the difficulty in fashion of mixing nostalgia and scale.

The Shuttle takes off

Marithé Bachellerie and François Girbaud started their company—called just Marithé et François Girbaud—in 1964. They built a name for themselves in their native France, and by the 1980s they had crossed over to the US (thanks to an endorsement from Flashdance star Jennifer Beals). Hip-hop has long had a close relationship with fashion, and as an aspirational, imported brand, Girbaud started getting name-checked in rap records from New York to New Orleans.

Clothing company I.C. Isaacs bought the license to sell Girbaud products in the US from Vanity Fair Corp. (the company that owns Lee and Wrangler, not the magazine) in 1997. Its most recognized design up to that point was the Brand-X, a simple five-pocket affair, said then-CEO Robert Arnot.

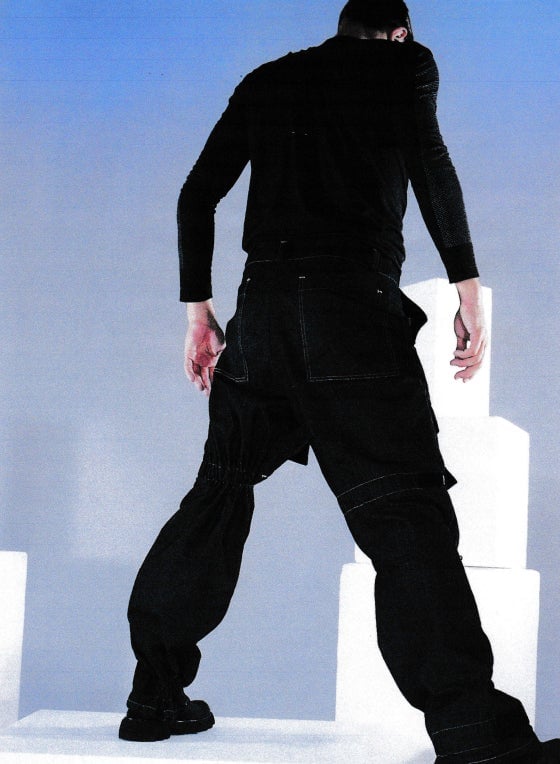

Then, in 1998, the company debuted the Shuttle. It featured a high waist, a baggy fit, and—the Shuttle’s signature feature—velcro straps that cinched the pants in the thigh and ankle.

François Girbaud said the Shuttle was based on a combination of military and space-suit design (hence the name), and anamorphic art, which distorts images for effect. It was a hit, and in many circles is synonymous with the Girbaud name.

“They were huge in America,” Girbaud said. “I don’t know how many millions we sold.”

Between the Brand X, the Shuttle, and other products, I.C. Isaac’s Girbaud sales would go on to peak at $83 million in 2005, before crashing to $37 million in 2007, the last year for which the company publicly submitted an annual report.

But like countless other popular labels popular with hip-hop from the early aughts, Girbaud fell out of favor, and the revenues soon followed. Arnot, who was only around until 2003, said the Shuttle was a huge part of the company’s surging sales after it debuted, adding that it was the biggest seller after the Brand X.

That said, Girbaud’s rap-fueled rise wasn’t always a comfortable one. François Girbaud made a stir in 2007 after a New York Observer reporter caught him expressing his discomfort with the label’s perception in the US:

When it comes to his own self-expression, Mr. Girbaud seems to think that the exigencies of marketing are cramping his style. “I have to talk like that”—he flashed a gang hand-sign—“and speak like that”—he flashed another gang hand-sign—“and move like that”—he grabbed his crotch—“and it’s ridiculous!” Now he was shouting. “What we bring into the market was always innovative, and I feel now I am trapped and I have to just talk the same way, like I have to have skulls and some kind of snakes. It’s boring, it’s really boring!”

Girbaud told Quartz he was simply expressing frustration that the company was being pigeonholed as a hip-hop brand—not trying to distance himself from the black and brown people who wore his clothes.

“I never worked for those guys, but it fit those guys,” he told Quartz.

Still, despite the declining sales, the cultural imprint of the Shuttle—and by extension Girbaud—had already been cemented for a new generation. The Shuttle made an appearance in the 2006 video for E-40’s “Tell Me When to Go” (1:33) and the brand got a shoutout on Boosie Badazz’s 2007 single “Wipe Me Down.”

Which is where Bsisso comes in.

A sonic boom

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay area, where E-40 is something of a legend, Bsisso was in the perfect place (high school) at the perfect age (14) for Shuttle jeans to get lodged in his memory.

“When I was in high school, and you didn’t have Girbauds, and you didn’t have multiple pairs, you were not him. You were not the man,” he told Quartz.

In the following years, people moved on from baggy jeans to skinnier ones. But in 2014, Bsisso he told a friend that he could bring the Girbauds back into style with the right tailoring. The friend gave him a couple of pairs he had lying around, and Bsisso put shears to cloth.

“It worked perfectly, and I was super-juiced,” he said.

He’s not the only one who’s been at it. When Brian Watts of Columbus, Ohio, moved from the city’s suburbs to its core in 2007 and into a new school, baggy Girbauds replaced other brands like American Eagle as the jean of choice. ”Kids looked like they could fit two of their legs into one leg,” he told Quartz.

Now 23, Watts started chopping up Shuttles in December 2014, and a couple of outside requests came in after word spread.

Indeed, spend enough time perusing search tags for “girbaud” or “girbauds” on Instagram and Tumblr, and you’ll find plenty of examples of similar engineering. Though Bsisso happens to be the only one making a market in them at scale, he wasn’t the first.

Back in 2013, Los Angeles boutique FourTwoFour on Fairfax produced a small run of tailored Shuttle jeans. Under similar circumstances to Bsisso, Guillermo Andrade, the shop’s co-owner, had approached his friend Elliott Evans with some pairs he had rounded up after a bout of nostalgia for the time they had spent together in the Bay Area in the mid 2000s, Evans told Quartz. FourTwoFour charged $375 a pair.

These high prices have a lot to do with the Shuttle’s famous straps. Tailoring a pair isn’t as simple as splitting the seam and removing the excess fabric; you also have to deconstruct the tunnels that hold the straps, cut the straps themselves, and put everything back together without rendering the straps ornamental.

The process is reminiscent of the one that goes into the $1,450 reworked denim that had Vetements making headlines last year. Bsisso, though, said he’s more inspired by likes of streetwear remixer Dr. Romanelli and Dapper Dan, the Harlem tailor who famously re-appropriated luxury labels in the 1980s for clients who couldn’t find their aesthetics on department store shelves.

Another reason for the high prices is that sourcing can be a pain. Between falling out of fashion and the financial crisis, Girbaud eventually declared bankruptcy in 2012 and liquidated itself in late 2013 (link in French). Nostalgic tailors are thus left to scour thrift stores, eBay, and online forums to find pairs to work on.

The pickings were even slimmer because people bought their jeans extra-loose for a baggier fit. “They’re hard to find in smaller sizes,” Evans told Quartz.

Failure to relaunch

Seeing the success of the slim Shuttles, however, the company that sold the originals wanted in on the action. Around the same time as the FourTwoFour project (but before the liquidation of Girbaud proper), I.C. Isaacs—now Passport Brands—relaunched the Girbaud brand in the US and almost immediately started contemplating a Shuttle redesign. Sean Mckoy, the brand’s lead US designer at the time, remembers being inspired by the tailored Shuttles he was seeing on US and French social media.

“It was like they were trying to do our jobs for us, but not really,” he said. “It was something that was needed, and something that was being asked for.”

Vic Lloyd, the co-owner of Detroit clothing store Fat Tiger Workshop, saw the results at the Liberty Fairs trade show in Las Vegas (pdf, p. 6) and bought 30 pairs. They sold out in about two weeks at a relatively breezy $120.

“It was a cool look but not as expensive as the people who were tailoring them down,” he told Quartz.

But when Lloyd went back to order more, they weren’t available. In May 2014, just three months after Fat Tiger was advertising the slim Shuttles, Passport Brands abruptly shut down.

“We’re in a state of flux right now,” said Ernest Jacquet, the company’s chairman. He declined to comment further because of ongoing litigation; several former Passport Brands employees sued the company for withheld pay after it closed shop. It’s still listed as an active corporation in New York, but has no employees, according to court documents.

Arnot, whom Passport brought back for the relaunch, said the company’s problems were more finance than fashion. ”Having people say it’s cool is great, but you need the other elements of the business to make it go,” he told Quartz.

The Girbauds themselves, meanwhile, seem to be plotting another comeback. They’ve been taking their show on the road in Europe with small, private sales for dedicated fans under the name Mad Lane (paywall). That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll start cranking out new Shuttle jeans, though.

“I don’t want to be interested in the past,” François told Quartz. “I want to be interested in tomorrow.” A spokesperson for Mad Lane told Quartz there were no immediate plans for a US expansion.

And, Bsisso’s operation aside, it’s not entirely clear if there’s enough of a market to sustain another full-throated Girbaud revival. Fat Tiger Workshop’s Lloyd doesn’t know if, given the chance, he’d order the slim Shuttles again. Evans, the tailor behind the FourTwoFour project, thinks the moment has come and gone.

“I think part of the allure is that it’s a novelty,” he said. “And if you they re-did it, it wouldn’t be the same as if a few pairs were floating around.”

Mckoy doesn’t think that’s true. He sees the Girbaud-inspired branding of M+RC NOIR and a recently released ($150) Shuttle jean take from Play Cloths (founded by the rappers Pusha T and No Malice of Clipse), and he posits that Girbaud’s most famous jeans still have enough relevance to make another go of it.

“Everyone remembers these jeans,” he said. “They were implanted in history.”