When Kenya issued its first sovereign bond two years ago, raising $2.75 billion, it was the biggest debut of any African country on the international bond market and further proof that East Africa’s largest economy was on its way up.

Now that Eurobond has become a symbol of what critics say is holding Kenya back: corruption and government mismanagement of public finances.

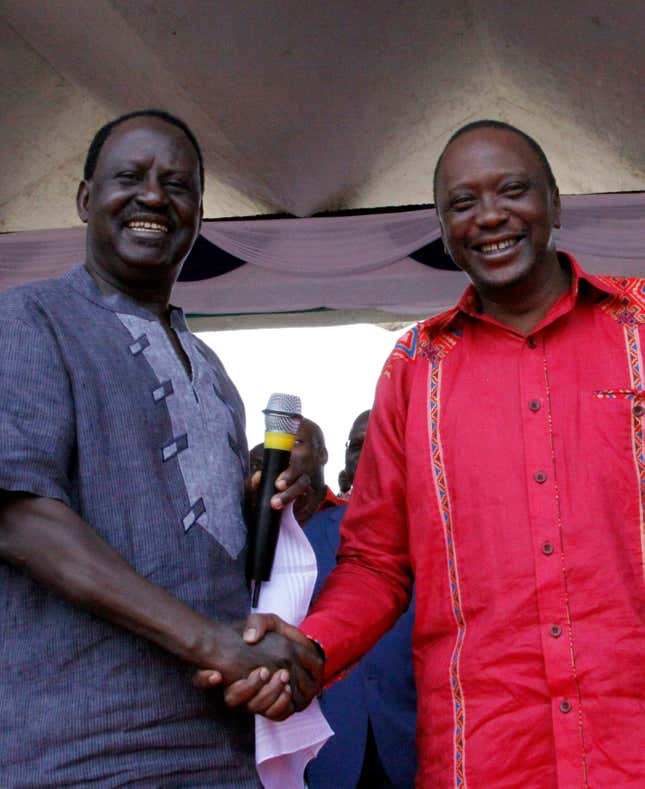

Debate over how the money was spent has become a tit-for-tat battle between president Uhuru Kenyatta’s ruling party and its critics. Opposition leader and former prime minister Raila Odinga claims the government cannot account for almost half of the money made from the bond issue. In the latest round, Odinga held a series of press conferences in Nairobi on Jan. 14, lambasting the administration’s ”elaborate scheme of deception.”

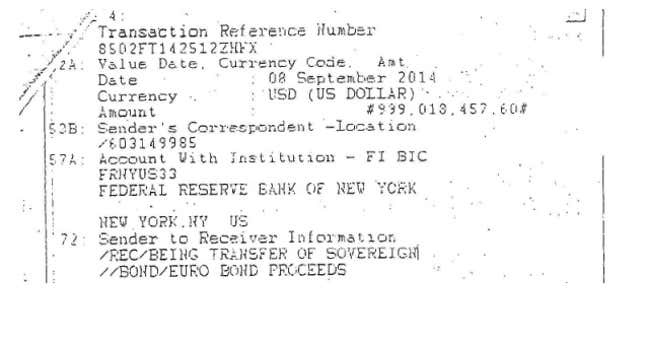

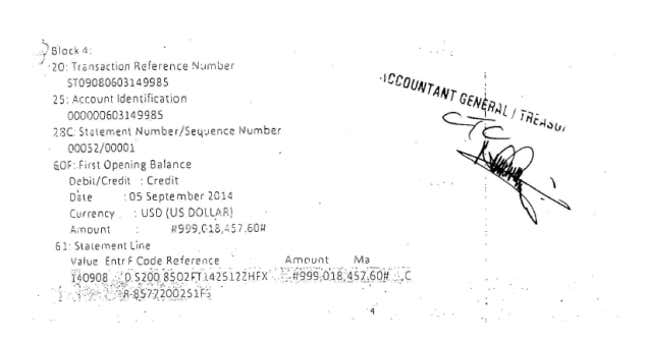

According to Odinga, $999 million of the proceeds from the Eurobond was transferred from the government’s account with JP Morgan Chase in New York to one with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on Sept 8, 2014, according to transfer receipts. He claims the money has not shown up in auditor reports for the last two years and that it was never deposited in the government’s public funds account. Odinga also called on US banks to give a full account of the funds and prove that they were “not part of this grand theft.”

“Nobody knows whose account it ended up in or whether it came into Kenya at all,” he told reporters.

Last week, Kenya’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission said it found no proof that any money from the Eurobond had been stolen. Treasury secretary Kamau Thugge said that the missing money was not on the budget for last year because it has been allocated for this financial year. “CORD’s is an issue of misreading the tables,” he told Bloomberg last month.

Odinga hasn’t quite proven to the public that the funds were stolen in what he claims is “an international money laundering” scheme, but neither has Kenyatta’s administration proven that the Eurobond—intended to lower interest rates, reduce inflation, and raise funds for infrastructure projects like geothermal plants, expanded airports, or a railway between Nairobi and the port city of Mombasa— has been a success. Public faith in the government is already low: Kenya ranks 145th out of 174 countries on Transparency International’s global corruption perceptions index.

“The Eurobond debacle has reduced confidence in the Kenyan government’s fiscal management ability and habit,” says Anzetse Were, a development economist and blogger. “It will be more expensive to borrow on international markets for the government. This has been evidenced by the fact that the rates on the Eurobond have gone up and the infrastructure bond floated by the CBK late last year got an initial rate of 11%, double what the government got from the Eurobond.”

Interest rates averaged 15.4% last year, making borrowing hard for Kenyans, and the rate of inflation, at 8% in December, has been consistently higher than the government’s target of 7.5%. Meanwhile, yields for the ten-year bond have creeped higher. On the Eurobond’s contribution toward the country’s infrastructure needs, Kenya’s cabinet secretary for the treasury, Henry Rotich, has been unable to specify which projects have been funded by the bond.

He said last month, “The ministries cannot differentiate whether the money they have received from the Exchequer came from VAT, income taxes, customs duties, excise taxes, domestic borrowing or the Eurobond.”