What we are witnessing right now is China reaching the tipping point on pollution

Pollution has become the Chinese public’s No. 1 political grievance, eclipsing bitter anger over corruption and land grabs, an official said. Concerns about the environment have captured an unusual degree of attention among officials at the two-week National People’s Congress under way now in Beijing. The Congress officially marks the transition to Xi Jinping as China’s new president and Li Keqiang as prime minister.

Pollution has become the Chinese public’s No. 1 political grievance, eclipsing bitter anger over corruption and land grabs, an official said. Concerns about the environment have captured an unusual degree of attention among officials at the two-week National People’s Congress under way now in Beijing. The Congress officially marks the transition to Xi Jinping as China’s new president and Li Keqiang as prime minister.

Anger about pollution fomented tens of thousands of public protests that erupted in China last year, said Chen Jiping, a retired member of the Communist Party’s legislative affairs body, in a March 5 briefing with reporters. An estimated 90,000 such protests broke out last year.

“Everyone cares about it now,” said Chen. “If you want to build a plant, and if the plant may cause cancer, how can people remain calm?”

For example of what he’s talking about, here’s a photo of Beijing in late February, as captured by Bill Bishop, which were widely published last week:

And in his address to the NPC on Tuesday, outgoing premier Wen Jiabao highlighted these growing concerns about the environment with an unusual degree of specificity (pdf). (Read this Bloomberg piece for a good blow-by-blow account of the Congress.) Though Wen declined to lay out what reforms would be made, change is already afoot. The Beijing government recently tightened vehicle emissions standards, and the central government is moving forward with laws requiring stricter fuel standards and curbing industrial emissions.

Public opinion is a powerful political driver (see No. 6 in Quartz’s indicators of energy geopolitics). As I have been writing for almost three years, the wealth and aspirations of ordinary Chinese can potentially disrupt not only their own local politics, but the presumptions underlying projections of global GDP, the growth of climate change and the power of OPEC.

The question, at least for me, has been “when,” rather than “if,” Chinese discontent would finally have an effect. A couple of researchers at Bernstein thought they perceived a tipping point last August. But we may be witnessing its flowering only now, as China’s officialdom admits that images such as the photo above are neither environmentally nor politically sustainable—and that it means compromising on the country’s three-decade-old dogma of GDP growth at any price.

If so, the ramifications include a potential shakeup of assumptions about the global economy, climate change and geopolitical power. Here is how these trends may affect the world beyond China’s borders:

Global economic growth. Projections reflect growth almost totally in the non-OECD world, with China as the main driver. But if the GDP-vs.-pollution calculus results in China scaling back growth, those forecasts will require adjustment.

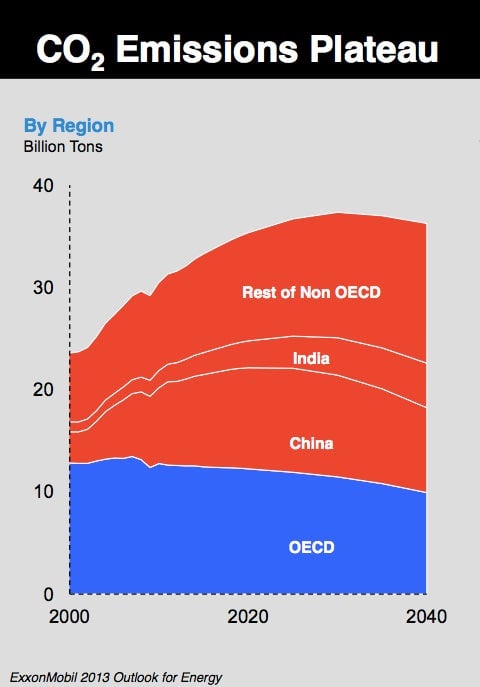

Greenhouse-gas emissions growth. China and India together produce most of the generally projected global increase of heat-trapping gases over the next two or three decades. Below is ExxonMobil’s forecast through 2040. But this picture could change dramatically if Chinese protests result in a cutback in the growth of coal consumption. As an example, CO2 emissions in the US have plunged to 1992 levels. China’s won’t do that, but they could grow more slowly.

Projected future oil consumption. Again, this relies mostly on Chinese and Indian demand. A Chinese policy shift—the encouragement of natural gas-driven vehicles, or a stronger push toward hybrid-electric vehicles—could deflate the country’s oil demand growth. The resulting shift in the supply-demand equation could cause global oil prices to plunge, affecting the backbone of OPEC and other petroleum-export-based economies. And that could have political effects: We have already seen the fragility of the Middle East’s elite.