It’s time to worry about the economy

It’s a funny thing about globalization. It works on both the way up and the way down.

It’s a funny thing about globalization. It works on both the way up and the way down.

For the last year the US has been an economic bright spot, in stark contrast to once high-flying emerging markets that powered global growth in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

The first two of the so-called BRICs—the formerly fast-growing emerging market nations of Brazil, Russia, India, and China—are suffering through downright nasty recessions. China is slowing fast. Outside the emerging markets, Europe inches along. And Japan remains Japan, last we checked, meaning very little growth.

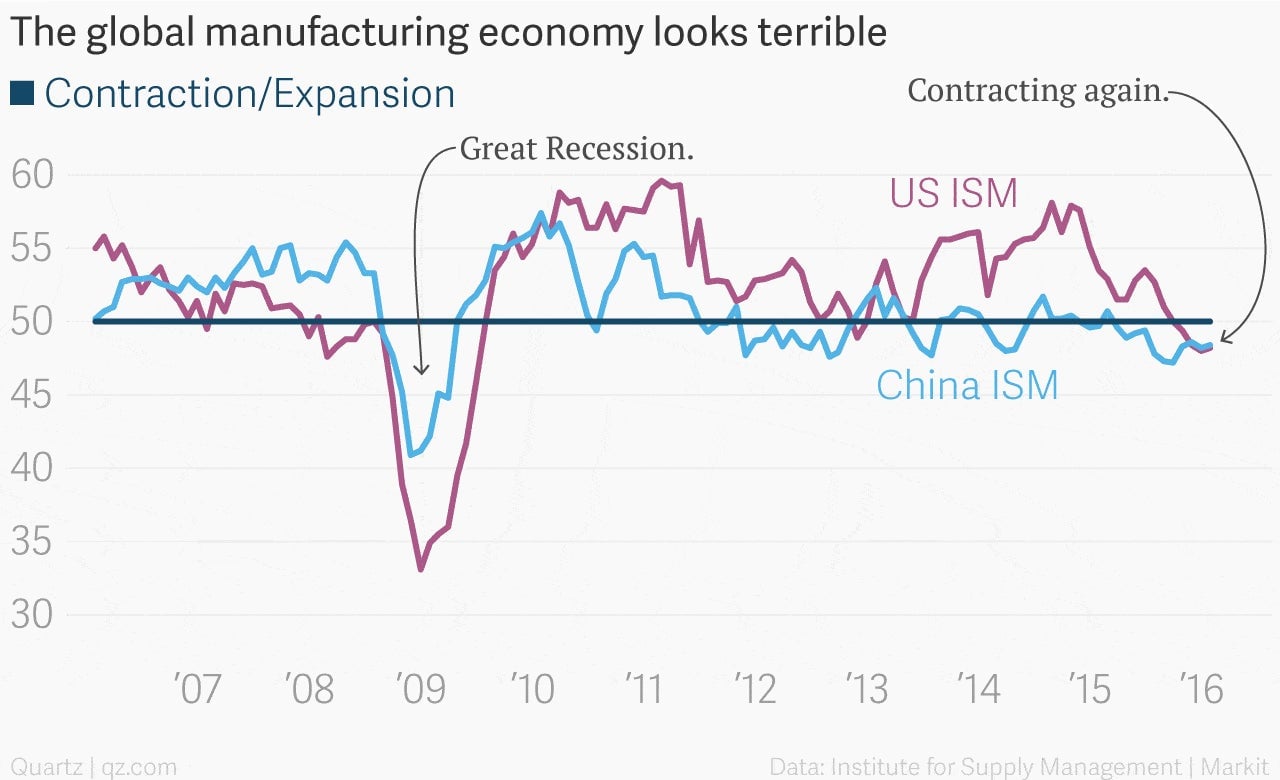

And now the brightness in the US appears to be dimming, at least a bit. The latest benchmark update on the US manufacturing sector shows activity continued to decline in January, marking four straight months of contraction. The strong US dollar—it’s up about 13% against the currencies of major trading partners—is a key culprit.

But the US isn’t alone. China’s manufacturing sector is shrinking, too, leaving us with the troubling specter of the world’s top two manufacturing economies in open retreat.

This is a bigger worry for China, where manufacturing represents a roughly 30% of Chinese GDP. (It’s a bit more than 10% in the US.)

But you’d be wrong to shrug off the US manufacturing sector as irrelevant. For one thing, nearly 9% of all US nonfarm jobs that are found in the sector. What’s more, decades of brutal integration into the global marketplace have given American manufacturers some of the most finely attuned economic antennae around.

That’s why it’s a bit troubling to see signs that even as new US manufacturing orders rebounded a bit in January, manufacturers seem intent on shedding workers. (The employment component of the US manufacturing activity index plunged even further into contractionary territory.) This suggests they’re prepping for a pretty substantial slowdown.

So does this doom the US to slip into recession? No. But it does increase the odds.

It’s true, there have been times recently when the US ISM manufacturing reading slipped into contraction mode without further incident. That happened in, for instance, late 2012, when the ISM report went negative amid the economy-rattling “fiscal cliff” controversy. (It quickly rebounded.) It also spent quite a bit of time in negative territory during the build-up to the war in Iraq in 2002-03.

But, as countries such as China have grown to account for larger and larger shares of the global economy, it stands to reason that their economies will have more and more of an impact on the US. Let’s hope policy makers are paying attention.