The Fed is making a huge mistake

Quick refresher: Under US law, the Fed essentially has two jobs, the famous “dual mandate.” It’s supposed to both maximize employment and keep prices stable. Over time the stable prices bit has come to mean an inflation rate of around 2%.

Quick refresher: Under US law, the Fed essentially has two jobs, the famous “dual mandate.” It’s supposed to both maximize employment and keep prices stable. Over time the stable prices bit has come to mean an inflation rate of around 2%.

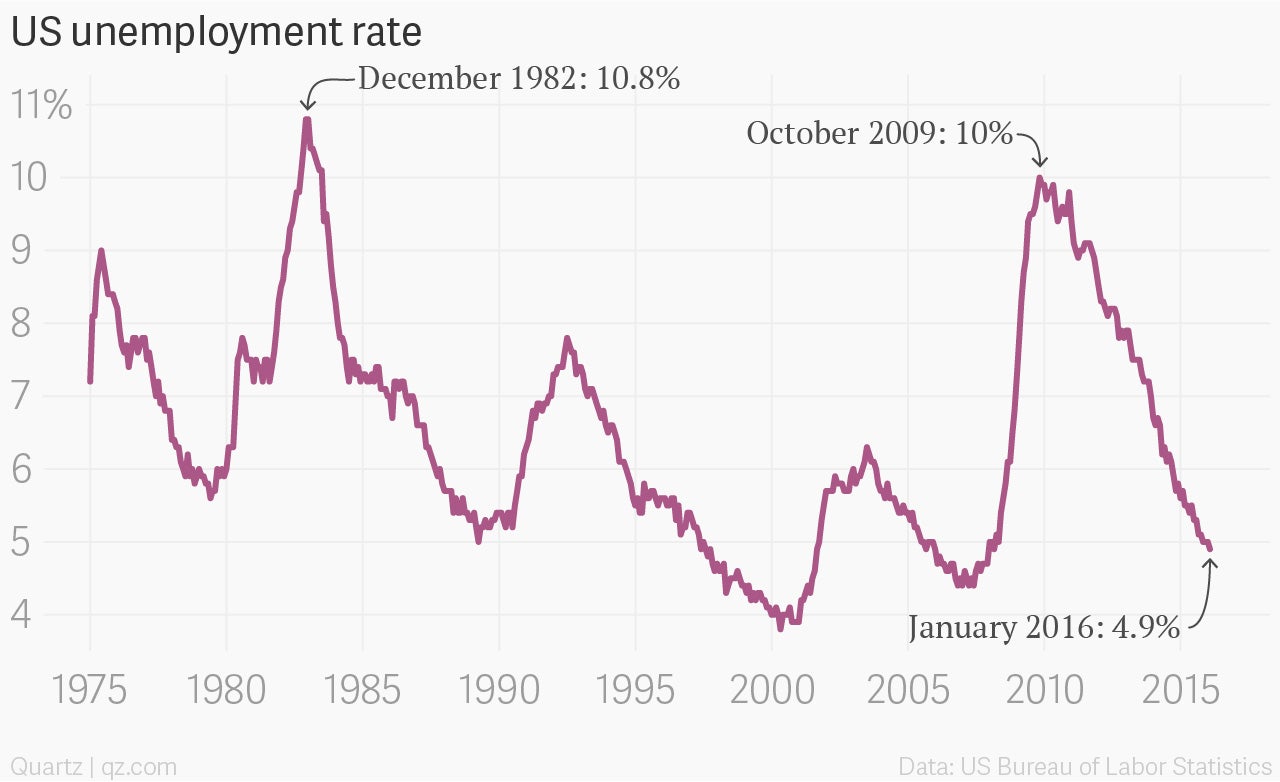

As far as employment goes, the Fed doesn’t seem to have too much to worry about. In January, unemployment punched below 5% for the first time since early 2008.

This isn’t all the Fed’s doing. But the long-recovery of the US labor market was supported at least in part by the Fed’s multiple efforts to boost growth in the aftermath of the Great Recession, including keeping interest rates very low.

So far, so good.

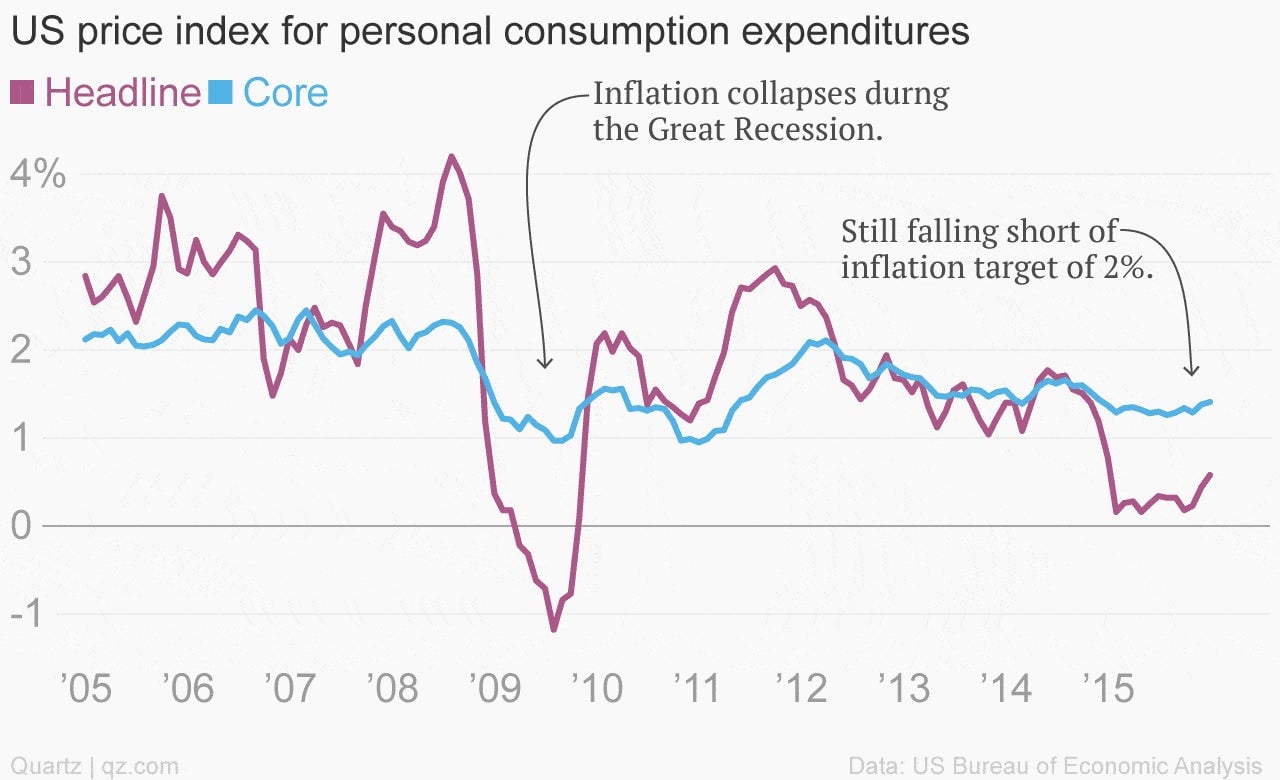

But the Fed continues to fail on inflation, as its preferred gauge remains far short of the Fed’s 2% target.

Much of this is a clear reflection of the collapse in oil prices, which have fallen more than 70% over the last two years.

The Fed believes that over time, as the historic drop in oil prices fades, inflation will gradually pick up, bringing price increases back to the bank’s target. In other words, it doesn’t think low inflation is anything to worry about. And on Wednesday (Feb. 10), that’s what Fed chair Janet Yellen said as part of her semiannual monetary policy testimony.

But there’s reason to be skeptical. For one thing, in order for the oil price decline to recede into history, oil prices have to stop, well, declining. And they haven’t. Over the last week (!) prices for US benchmark crude oil futures have fallen 14%, putting the price of a barrel of oil below $28.

More importantly, the oil price decline—while historic and unexpected—isn’t happening in a vacuum. It reflects the broader weakness of the global economy.

China, the world’s second-largest economy, appears to be in full flounder. That has spread to a range of large economies—Brazil, Australia, Canada among them—that have organized themselves around digging up and selling the raw materials China has consumed in abundance over the last two decades.

And China’s slowing factories are cutting prices like crazy. Prices at Chinese factory gates were down 5.9% in December compared to a year earlier, which means the world’s largest exporter is now a large-scale exporter of deflation.

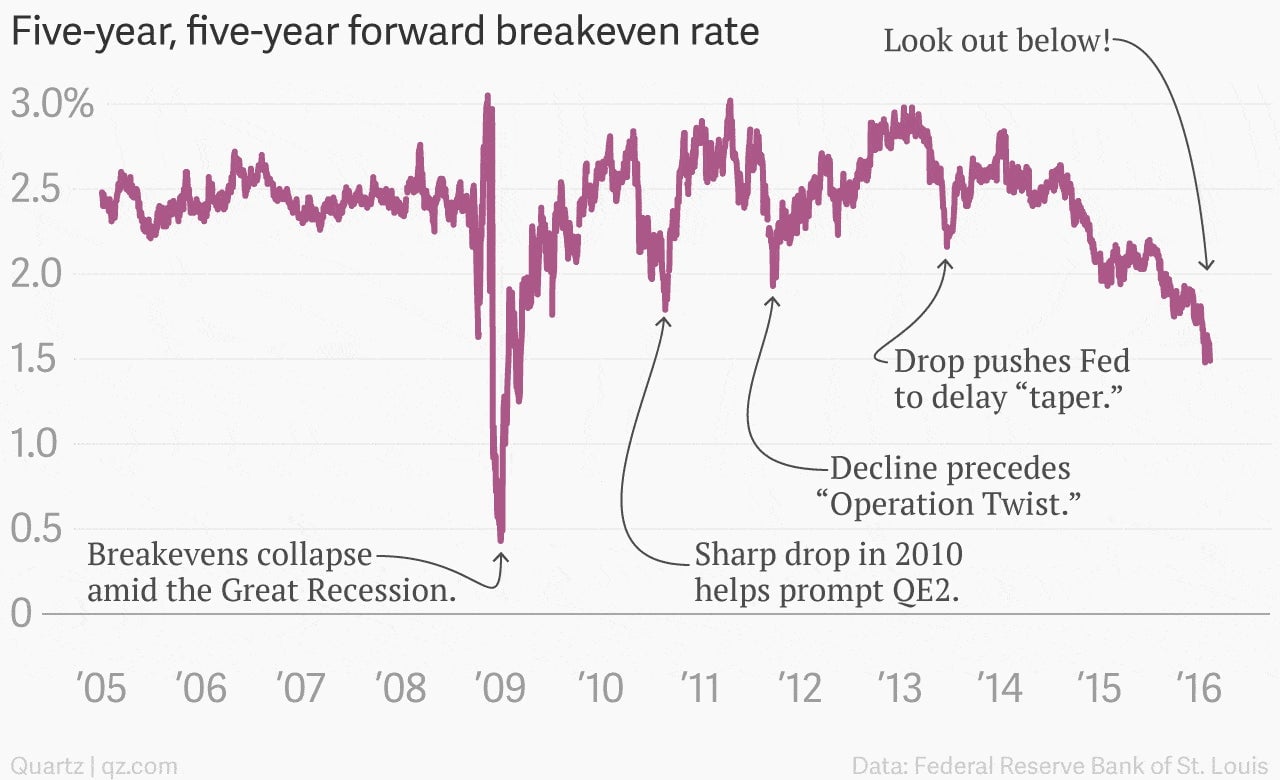

But perhaps most concerning is the fact that there are clear signs that a deflationary psychology is starting to take hold throughout financial markets. Economists have long stressed the danger that expectations can become reality when it comes to both inflation and deflation.

So why are deflationary expectations creeping in? One reason is the performance of negative-yielding government bond markets this year.

When you buy a bond with a negative yield, you’re effectively paying a borrower to take your money. It would seem to guarantee a loss. But lo and behold, investors have piled into bonds of countries like Japan and Switzerland—much of which promise negative yields—making them some of the best performing assets around.

And there’s also the gauge the Fed pointed to throughout much of the aftermath of the Great Recession. This is the so-called five-year, five-year breakeven inflation rate, which is a measure of expectations for where interest rates will be in the future. In the past, the Fed has acted when this gauge has come close to falling below 2%. More recently the Fed’s made no effort to prop it up.

For its part, the US central bank has repeatedly said it has doubts about whether the five-year breakeven rate captures expectations accurately. That’s kind of missing the forest for the trees. While the scale of the decline in breakeven expectations is an outlier, the direction isn’t.

Deflationary pressures are everywhere. From the strong dollar, to low oil prices, to low import prices, to global declines in equity markets. The Fed needs to take note. The risk to the global economy isn’t inflation. (If it was, clinging to the notion of more rate hikes would make sense.)

No, the risk is deflation. And the risk is real.