iPad is poised to evolve tablets, if only Apple can figure out what tablets are supposed to be

I once called the iPad a tease, promising more “PC-replacement” capabilities than it could deliver. The iPad Pro tried again, but many—yours truly included—feel it’s still a better tablet than laptop. Hope springs eternal: today, we look at yet another—putative—step in the iPad’s future.

I once called the iPad a tease, promising more “PC-replacement” capabilities than it could deliver. The iPad Pro tried again, but many—yours truly included—feel it’s still a better tablet than laptop. Hope springs eternal: today, we look at yet another—putative—step in the iPad’s future.

Last week’s Monday Note, “Roasting Toaster Fridges,” left some business unfinished. After opining about the hard-to-finesse constraints in Microsoft’s and Apple’s hybrids, and praising the agile 12” MacBook for its laptop purity, I ended with a few half-cooked, hanging phrases about future AX processors, cannibalization, and the aging OS X versus the younger iOS.

This unfinished business was rewarded with vigorous private email drubbings and demands that I be more specific.

Well, here it is: The iPad Pro’s last frontier is adding a trackpad to the Smart Keyboard.

Consider the Surface Pro’s Type Cover:

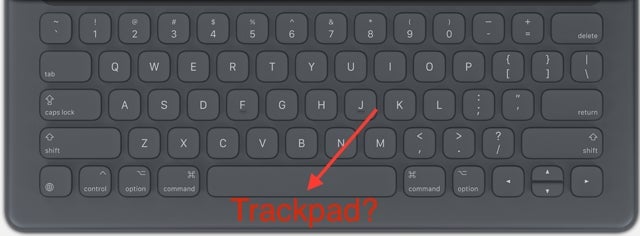

and Apple’s iPad Pro Smart Keyboard:

The next step seems obvious: Add an Apple-quality trackpad et voilà! A fully dual-mode tablet/laptop.

Easier said than done. Let’s see if we can do what a good lawyer is supposed to be capable of—that is, plead both sides of the hybrid question.

First, the argument against.

It’s our contention that the addition of a keyboard and trackpad has bastardized the iPad, a device whose beautifully simple touch-screen interaction finally allowed the tablet genre to take off. It’s a belt-and-suspenders complication, an admission of weakness that will further confirm people’s doubt about the future of tablets.

Why “further confirm?” Consider the file system: Early versions of the iPad’s operating system were criticized for not having one. Of course, any operating system must have a file system, but iOS kept it hidden from users, many of whom were intimidated by conventional PCs. It was a laudable idea, part of the mission to use simplicity to break through the decades of unsuccessful attempts to breathe life into the tablet genre.

But as the iPad grew in popularity, it reached many market strata, including users who wanted to “build things” but were frustrated by the inability to combine document components into a complex finished product. These discontented customers wanted a proper file system—a way to navigate local and cloud document repositories.

And now they have one… sort of. iOS exposes the iCloud drive, and gives access to DropBox, Microsoft’s One Drive, and others. But the look and feel is different from what one gets on a conventional PC. For example, the Pages document for this Monday Note appears in both a dedicated iCloud drive Pages folder and in the “MN 405” folder elsewhere on the drive. And why do the .png files at the top of this article live in a Preview folder and in “MN 405”? (405 Monday Notes; yes, that many in almost nine years.)

Compare this to Dropbox on a combined Mac and Cloud store where everything is in one place.

Similarly, iOS recently added a split-screen mode in order to enable multitasking. But it’s not as simple or as functional as the polished, classic PC interface with movable widows, tabs, pull-down menus, and a mouse. Users don’t want an inferior imitation.

In conclusion, Your Honor, one could choose to see these changes as evidence of progress—a transition, uneasy, perhaps—between minimalist origins and catering to the needs of more demanding users. But adding a trackpad to the iPad Pro’s Smart Keyboard will not solve any of the tablet’s problems. The clumsy graft would only make the iPad more complicated, blur its identity, and cloud its future.

Now for the defense.

Consider Apple’s fiscal year 2015 numbers. In round numbers, the company sold 231 million iPhones, 55 million iPads, and 21 million Macs. (There’s no word of iOS-based devices such as Apple TV and iPod Touch; they’re clearly no longer or not yet significant.) Regrouping by operating system, we have 286 million computers running iOS, and 21 million running OS X.

If you’re the Chief Resource Allocator, which battle must you win, no ifs, no buts, no “it would be nice to…”?

iOS is your key to the future.

OS X and iOS share some technologies, but while one is big, bloated, and buggy, the other was created as a fresh start. Yes, iOS is based on OS X, but it was vitally pared down so it could run on the 2007 iPhone’s very weak ARM processor. In the paring down process, much of the old OS X scar tissue was removed

In a recent John Gruber podcast, Craig Federighi, Apple’s head of software, attempted to reassure OS X doubters: ”I know our core software quality has improved over the last five years and it has improved significantly.”

I guess Federighi doesn’t consider iTunes and Mail to be core software. For more than five years, my daily use of Mail has been plagued with bugs.

Only last week, I set up an account on my spouse’s Mac because I had misplaced my own machine. Things went well at first—I got my apps and documents without trouble. Then, suddenly, Mail refused to work. It would launch and quit right away, repeatedly. No workaround (other than webmail). I verified the hard disk, restarted multiple times. No joy.

Three days ago, I opened my MacBook and got four crash messages: Mail, System UI, App Store, and, if I recall correctly, mds_stores. In any event, my Console log is available upon request—and I know crash messages are automatically sent to the company. (I must add that I’m impressed by how processes restart automagically without intervention—Mail aside—and how I never seem to have lost data.)

The OS X side of the house seems to have entered an undebuggable era of putting patches on patches and needing more patches as a result. This is always the case for aging software.

Contrast this with iOS. Calculated or instinctual, iOS was a stroke of genius, a rebirth of OS X redeemed of its old sins (well, most of them). Yes, the original iOS lacked basics such as cut-and-paste, accented characters, and support for native apps, but instead of a daily struggle to fix existing functions, the iOS team was free to reinvent the features that had been sacrificed in the original version—and create some new ones.

Comparing OS X and iOS memory and disk footprints isn’t straightforward. Among other factors, the parallel depends on which system apps and libraries are brought into the picture. iOS was engineered to run on a tiny footprint: 128 megabytes on the first iPhone, an amazing accomplishment at the time. Today’s iOS may seem bloated by comparison—2GB on the iPhone, 4GB on the iPad Pro—but the Mac has always needed much more memory. Except for the 11” MacBook Air and the Mac mini, it’s not offered with less than 8GB of RAM. On disk, iOS fits within 2GB; OS X, with libraries, needs roughly 10 times more disk storage.

From any angle, OS X is a well-liked, very capable, complex operating system…but there’s little hope of clearing its clogged arteries. iOS is the future; according to Tim Cook, it now runs on one billion devices.

From that perspective, the path forward isn’t hard to divine. Over time, the iPad Pro and its progeny will become more capable of performing tasks that, today, are better suited to laptops. The addition of a trackpad will be a natural and welcome evolution.

I rest my case.

* * *

Of course, if Apple does add a trackpad, Microsoft execs and users will say that they were right all along. And perhaps they were: They had the right idea but the difference is in the implementation.

On the Microsoft side, we see tablet features grafted onto a legacy operating system that’s even more riddled with old age issues than OS X.

On the Apple side, we’ll see the continued absorption of laptop capabilities by an agile and efficient OS that was designed for touch-based interaction on smaller devices. Extrapolating from past evolutions, one can see a future iPad running Microsoft Word and Excel, or Apple’s Pages, Numbers, and Keynote as effectively and pleasantly as today’s MacBook. If you remove the keyboard-trackpad combo and pick up the Pencil, it becomes a pure tablet for drawing or CAD purposes.

With its control over software and hardware, Apple is positioned to evolve the tablet genre. The iPad mini seems destined to stay a pure tablet, but more muscular members of the family will steal business from laptops—Apple’s and others’. “It’s better to cannibalize oneself than let others do it” has, rightly, been Apple’s position.

As the first iPad Pro shows, we’re not there yet—the iPad is still best used as a tablet, the Mac isn’t going away any time soon. Some of us are habituated to our Macs, but habits aside, there are graphics and video apps and hardware configurations—large screens as an example—that require more power than the Apple-designed AX processors can offer.

But for how long? That’s a question for both Intel and Apple to answer.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.