Is there anything new to learn from America’s conservative budget?

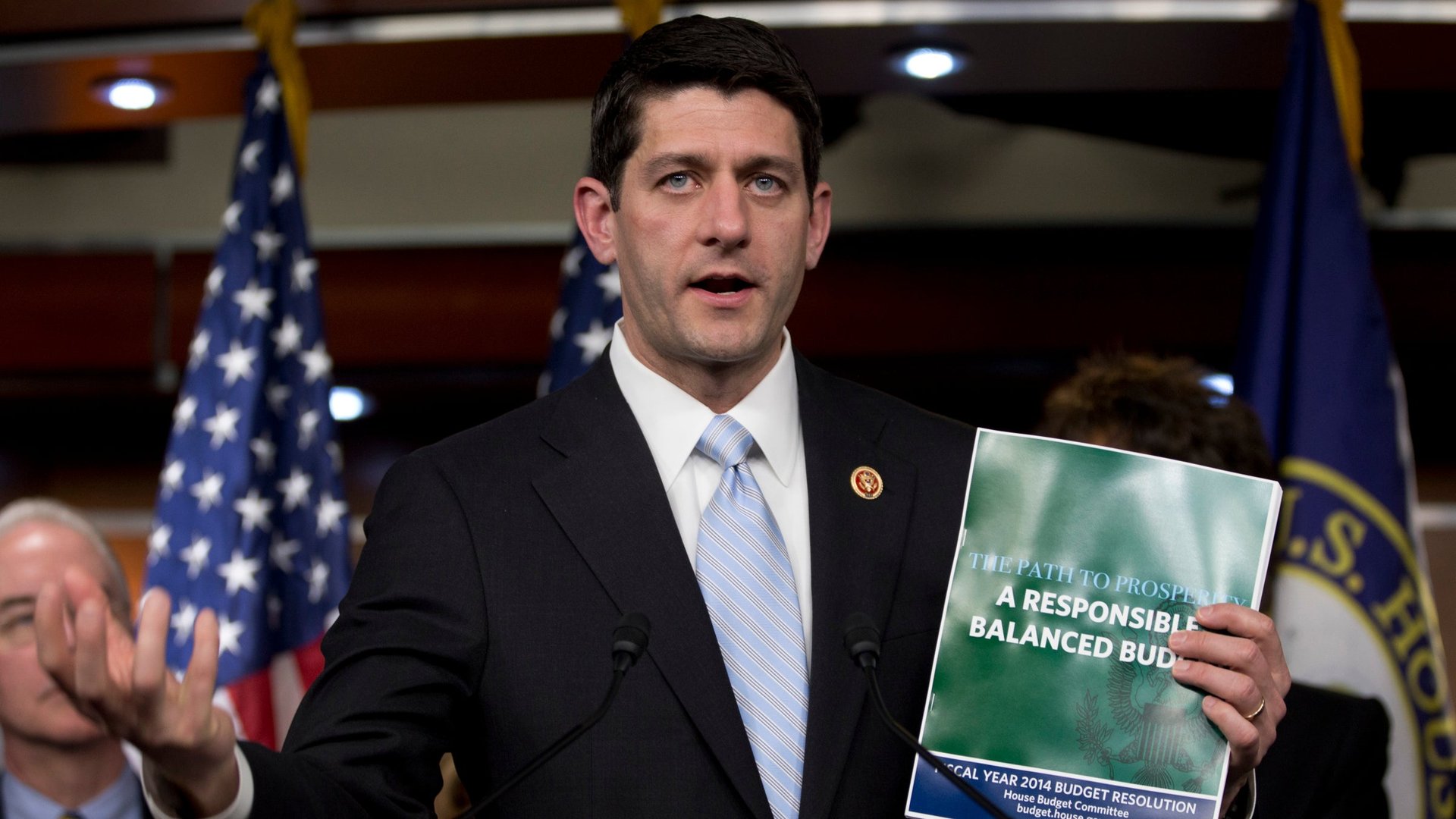

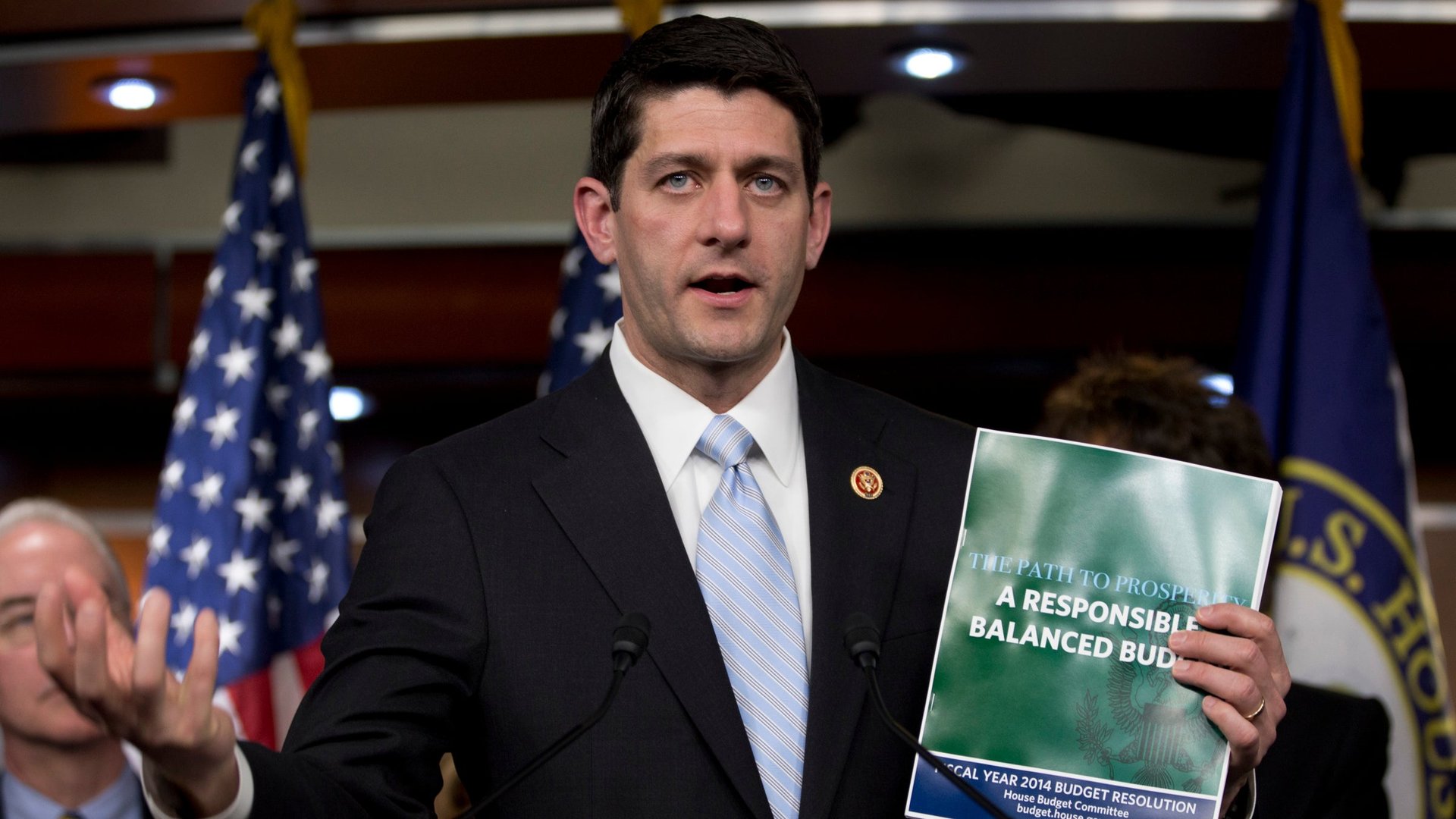

The Republican chairman of the House budget committee released the budget plan representing his party’s vision for America’s fiscal future today.

The Republican chairman of the House budget committee released the budget plan representing his party’s vision for America’s fiscal future today.

That’s exciting, but Paul Ryan, the chairman and erstwhile vice presidential candidate, has been the architect of these plans for several years now, and we know what we’re getting: Less of the taxes he sees burdening Americans, less of the government services he sees as weakening them, and little clarity on what those policies would do to the deficit. Highlights include:

- An unspecified plan for tax reform that promises to maintain current levels of revenue—including those raised at the end of last year, a step towards the middle—while still offering a major reduction in the top rate for the wealthy to just 25%, among other cuts. Doing this would require eliminating many, many tax deductions, including the most popular credits for low- and middle-income tax payers, effectively raising their taxes.

- The half-twist repeal of Obamacare: End the universal coverage, keep the tax increases and the cost savings—although many of the cost-savings come as part of universal coverage.

- No other changes to Medicare, the health care program for seniors, for a decade. Then it switches to a private system that will pull back government support, shifting more of the cost onto seniors.

- An effective increase in Defense discretionary spending, but a plan to take advantage of $629 billion in war draw-down costs, a classic bipartisan budget gimmick.

- More cuts to domestic discretionary spending—on education, research, land-management etc.— he’d cut an additional $1.5 trillion from discretionary spending on top of sequestration cuts already mandated by law.

- A 25% cut to Medicaid, the health program for the poor, amounting to $1 trillion dollars over 10 years.

- Cuts to food stamps and welfare programs.

- No changes to Social Security in the next 10 years.

All this adds up, in Ryan’s budget, to a balanced budget within the decade, his stated goal. However, the massive reorganization of the American state implied by the plan, not to mention the challenge of making the tax reform proposals add up, make this a very rosy projection. At least he’s sticking to the CBO’s economic projections this time (although both are, frankly, rosy).

As James Pethokoukis points out, the problem here is that Ryan is a slave to his party’s political needs, which include not angering seniors in the near term (i.e. not messing with their public health and pensions), advancing a radical low-tax agenda, not cutting the military, and rapidly reducing the debt. It’s not that all of Ryan’s ideas are politically infeasible—there are versions of his Medicare scheme that attracted Democratic supporters like Senator Ron Wyden, although Ryan is no longer backing that particular plan.

America’s long-term budget challenges are in the costly health care and defense spending Ryan can’t touch. A bipartisan deal to reform the tax code could lower rates and raise revenue (while making the system more efficient.) But increasing America’s globally-low tax revenue is verboten for the GOP, especially after it allowed some of the Bush tax cuts to expire at the end of last year.

And the big question everyone is asking about this budget is, “Why balance it in 10 years?” Debt reduction requires the economy to be growing faster than borrowing is increasing (and it is), not that public borrowing end after some arbitrary time period. A balanced budget isn’t necessarily a good thing anyway.

One thing we have learned today: After five years of pushing his fiscal roadmap, Ryan is not any further along to advancing his policy agenda than when President Obama took office, despite the success of Republican opposition in hindering some of the White House’s agenda. Given the Democrats’ reluctance to change their budget priorities—which include spending reductions, including for public pensions and Medicare, balanced with tax hikes—without GOP concession, the final say on spending for 2013 will probably look a lot like last year’s. That is to say, a budget deal that defers most hard choices. That’s not the worst case scenario, but it leaves some low-hanging fruit on the fiscal tree.

We’ll learn more about the track of this year’s budget fight—heading for a March 27 deadline—when Senate Democrats release their counter-offer tomorrow.