The United States has a first-world problem. Or at least that’s what the Congressional Budget Office reported in its 2013 budget and economic outlook (pdf), the document that sets the benchmarks that lawmakers will use to fight over America’s fiscal path.

The forecast is fairly simple: If Congress does nothing at all, US deficits will continue to drop until 2017, when they will start gradually rising again. A decade from now, debt held by the public will be 77% of GDP, up from 72.5% now.

There are two trends driving those projections, and it all has to do with US demographics:

- Growth is slowing! After bumping up to 3.4% next year, GDP growth will slow into the latter half of the decade to about 2.2% annually. Is there a reason, CBO? “The main reason is that the growth of the labor force will slow down because of the retirement of the baby boomers and an end to the long-standing increase in women’s participation in the labor force.”

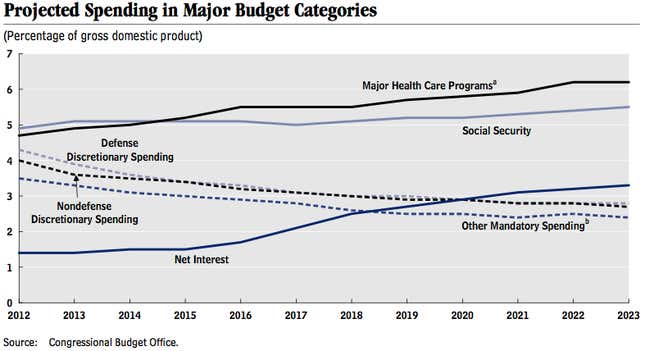

- The government is spending more money! And it’s spending it on old people. Think of it this way: By 2023, the annual gap between spending and revenue will be about 3.3% of GDP. In that same time period, the share of spending on Social Security pensions and health care (mostly Medicare, for seniors) will grow by 1.6% of GDP—more than half of that deficit. At the same time, net interest spending on the debt will increase by 1.9% of GDP. Maybe a picture will help:

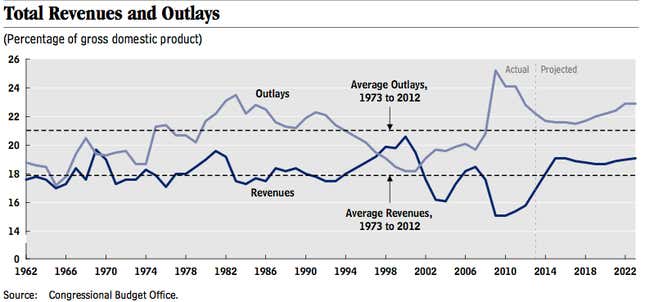

By contrast with the increasing cost of healthcare and pensions, discretionary spending–on highways, defense, research, education, financial regulation, etc.—has been dropping as a share of GDP. And in 2012 it also dropped in nominal terms—only the fourth time that has happened since 1962. Tax revenues over the next decade, meanwhile, are expected to bump up to 19% of GDP, below what’s needed to cover outlays, above the average for the United States and well below the share of taxes collected by most other advanced economies.

In short, the US is running into a problem faced by many other rich countries: With a shrinking workforce, how do you maintain the social compact to older generations?

In most other countries, part of the answer is higher tax revenue. President Barack Obama will make this case—and his suggested increases would still leave the US among the lowest-taxed advanced economies in the world. American lawmakers have been focused on reducing health-care costs, and there’s some silver lining there: Following reforms in Obama’s 2010 health care law, spending on Medicare (health insurance for the elderly) in 2012 grew at the slowest rate in over a decade, and the agency reduced its future projections by some 15%.

Right now, lawmakers are debating how to replace the automatic spending cuts (the “sequester”) due to kick in on March 1—which could spell bad news for the US economy—with a more growth-friendly way to reduce the deficit, but it’s not clear they’re listening to what the CBO is telling them. Republicans remain unlikely to increase taxes further, but Obama won’t cut a deal unless they do; meanwhile, the spending cuts the president has offered, some $925 billion, mostly to the mandatory programs driving growth, may not be immediate or large enough to satisfy conservatives.

More gridlock and indecision on fiscal matters wouldn’t be the end of the world; as we’ve said, the deficit is currently gliding downwards as the fiscal costs of the recession are reduced; a bigger pressing problem is high unemployment that will stand above 7% until 2014, the longest time that’s happened in US history.

But by 2017 the country will start to see more problematic structural factors take hold. A successful overhaul of the country’s immigration system could help buy time, boosting the working population and stimulating the economy. But eventually America will need to make a decision about what its changing population means for its public pocketbook.