The story behind one school’s solution to keep helicopter parents at bay

When George Davison, head of Grace Church School in Manhattan’s East Village, was designing a new high school, he had many goals: open areas for collaborative work, a library to reflect the technological needs of 21st-century kids, and a space for kids to complete major projects away from the prying eyes of their helicopter parents.

When George Davison, head of Grace Church School in Manhattan’s East Village, was designing a new high school, he had many goals: open areas for collaborative work, a library to reflect the technological needs of 21st-century kids, and a space for kids to complete major projects away from the prying eyes of their helicopter parents.

Design thinking, it seems, has extended to protecting students from their parents.

“If a project is mainly done at home, it’s impossible to keep the parents out,” Davison tells Quartz. “The helicopters are too strong.”

Science projects are notorious for attracting the attention of earnest parents. Teachers at Grace Church trade infamous tales about over-the-top projects—a hovercraft, a water-powered car built with copper piping—that 14-year-olds innocently submitted as their own work. These, in part, inspired the design of the new school.

Grace Church’s high school, which opened in 2012, gave Davison and his team the chance to work from a blank canvas. They looked to create open spaces and build time into the school day for kids to make things away from their parents. “It is hard to have the space to hold the imagination of the kids,” Davison says.

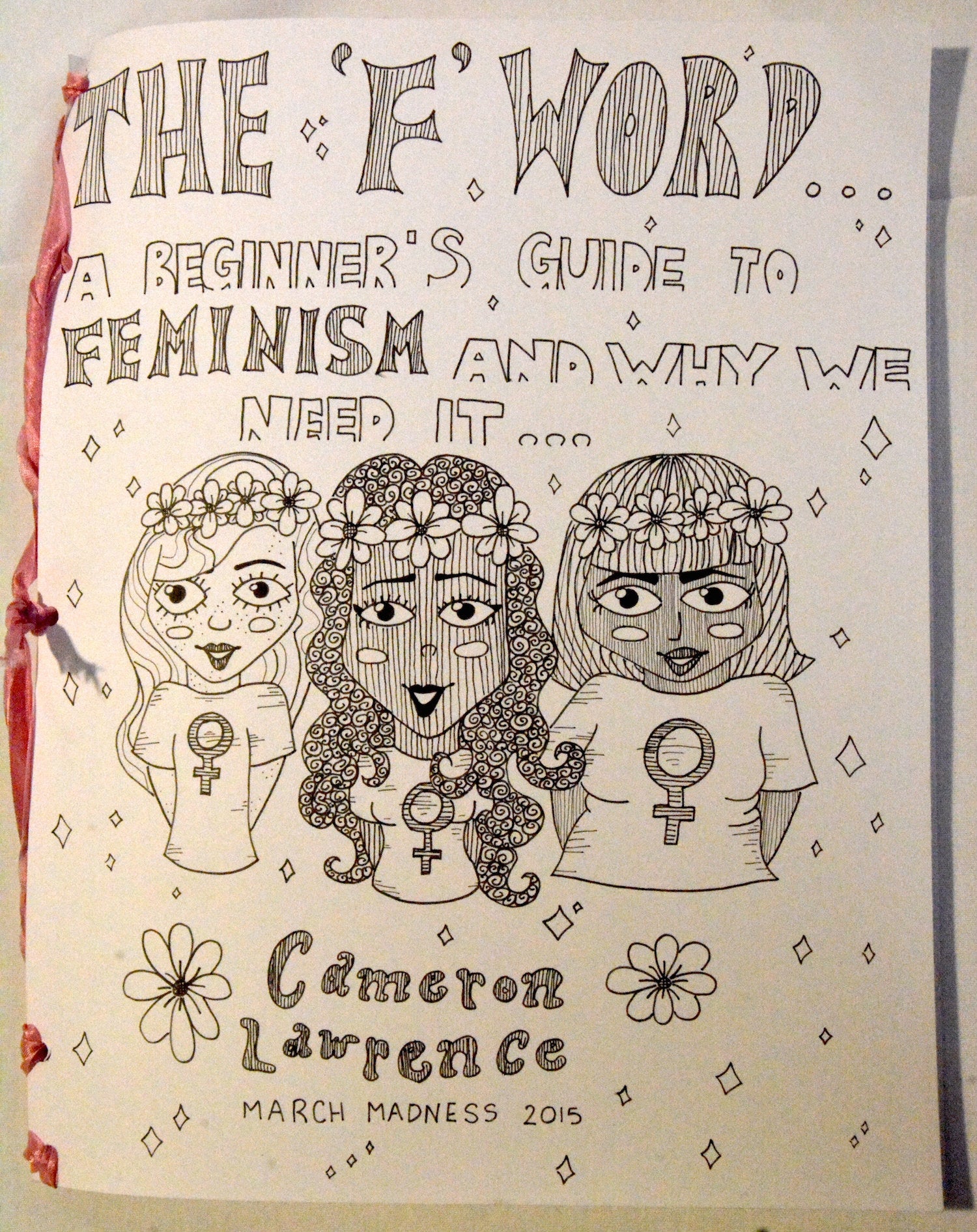

Borrowing from the international baccalaureate program, all 16-year-olds have to complete a project related to something they are passionate about. The school calls it March Madness, named after the annual college basketball tournament. Kids get one hour every Wednesday to do it in ”maker’s spaces,” rooms where they can design big things and store them.

For the two weeks leading up to spring break, the kids take only one class in the morning, freeing up the afternoon to work with a mentor on their special project.

The students let their imaginations run wild. One kid created his own chewing gum. Another designed the ultimate luxury airline seat. One teen’s graphic novel on feminism and multiculturalism was featured in Teen Vogue. A particularly devious kid designed the perfect financial crime, with the help of a contact at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The project is meant to engage the parts of the brain that aren’t active during the standard reading and writing exercises, but come alive for tasks that require planning and designing.

Students are overseen by adult mentors, but never parents. “You want to keep parents out because their presence undermines the students’ feeling of success,” Davison says. The teens don’t benefit from the pride of ownership if the ownership is not wholly theirs.

Parents are getting more involved in their kids’ schoolwork over time, a trend attributable to many factors. Parents don’t want their children to fail. They spot an opportunity to work on a project that could become fodder for the all-important college essay. They want their kids’ to outcompete their friends’ and rivals’ kids.

“There is a social element among parents,” says Davison diplomatically. “They don’t want their kid to be the one who doesn’t have the spectacular project.”

Jessica Lahey, a teacher and author of The Gift of Failure, wrote about her decision to let her son turn in a very mediocre project:

We’ve all been there, usually around 11 on the night before a child’s project is due, reluctantly stepping over the line between helping and taking over. It starts out innocently enough, as, “Here, let me help you cut those last pieces out so you can get to bed,” and quickly snowballs into a lie, a Ph.D. dissertation in third-grade handwriting.

In spite of Grace Church’s best-laid plans to keep parents out of the March Madness project, they still try to get in, Davison says. But they have to make it through two layers of adults first: the dean of students who oversees all projects, and their kid’s individual advisor. That’s applied design thinking.