I know Hong Kong is over—because my mother has stopped watching TVB

They say Hong Kong is “Asia’s world city,” an international financial center, a free, cosmopolitan society populated by not just skyscrapers but global citizens who have come here to seek opportunities that will bring them fortune and help them realize their dreams.

They say Hong Kong is “Asia’s world city,” an international financial center, a free, cosmopolitan society populated by not just skyscrapers but global citizens who have come here to seek opportunities that will bring them fortune and help them realize their dreams.

In reality, however, this is nothing but an urban myth. I will tell you how I know: My mother has switched off TVB.

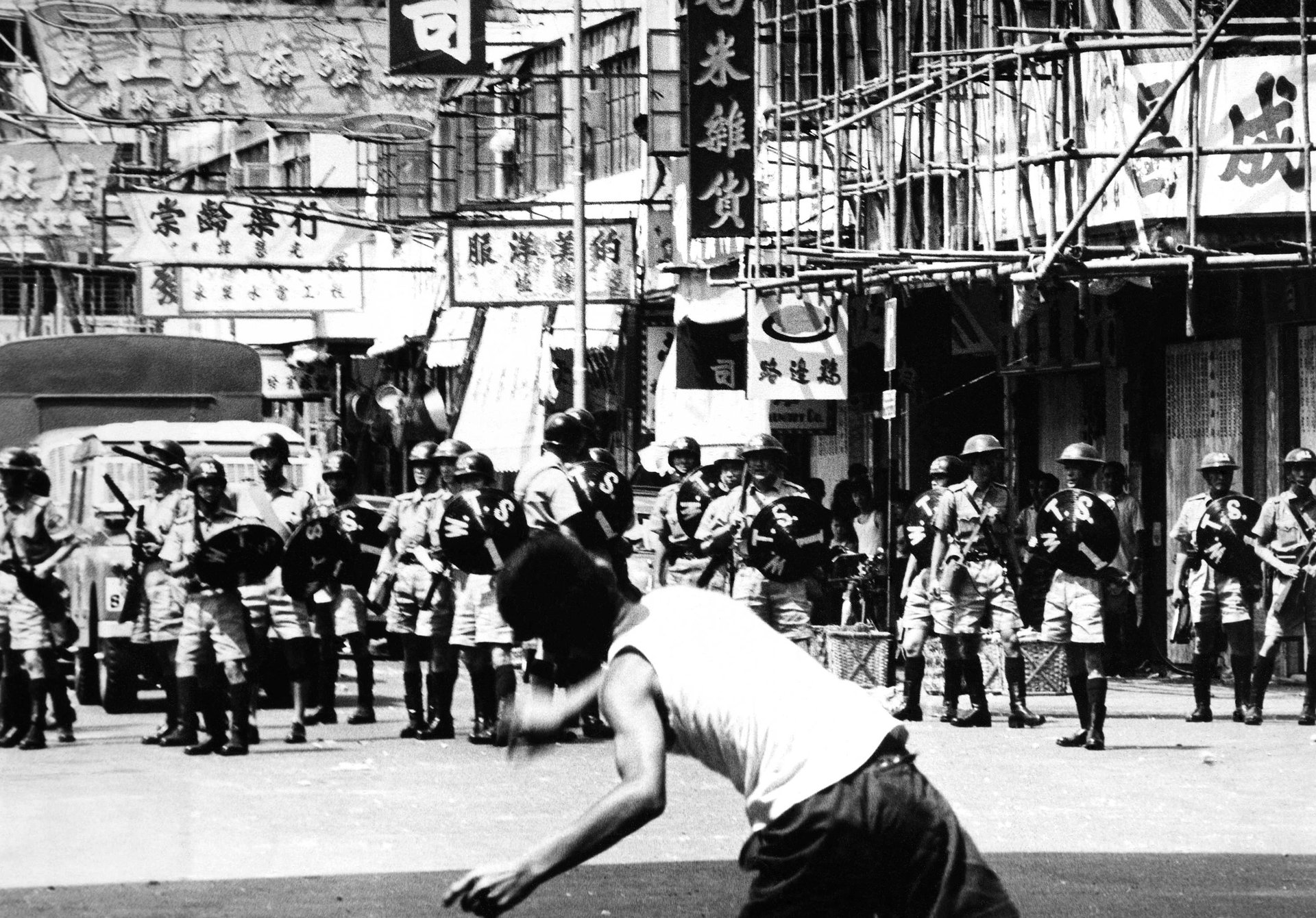

If you’re not a Hongkonger—someone born and bred in the city who speaks the local language of Cantonese—let me explain. Hong Kong’s dominant free-to-air television station is Television Broadcasts (TVB), which has been in operation since the 1967 riots that changed the course of the city. The city’s first free TV station, co-founded by movie maker and philanthropist Run Run Shaw, was inaugurated when Hong Kong was recovering from the leftist riots that left 51 dead.

It was a watershed moment, as the city moved on from political turmoil to prosperity in the 1970s. The daily live variety show Enjoy Yourself Tonight was a key reflection of the changes in lifestyle.

My mother, a Hong Kong–born, primary-school-educated housewife in her late 50s, grew up in a public housing estate and speaks little English. She is the target audience for TVB Jade, the Cantonese-language channel that has been number one in my home for as long as I can remember.

We grew up watching TVB programs, most notably the long-running family drama A House Is Not a Home (1977), the crime thriller The Emissary (1982), the comedy The Justice of Life (1989), and the hilarious sitcom War of the Genders (2000). Such shows—products of a vibrant entertainment industry that once dominated Asia—helped shape Hong Kong’s cultural identity, as scholar Eric Ma Kit-wai has put it, and exported the city’s identity and language abroad.

Many of today’s brightest actors and directors—among them Chow Yun-fat, Andy Lau Tak-wah, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Stephen Chow Sing-chi, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Wong Kar-wai, and Johnnie To Kei-fung—shone at TVB from the 1970s to 1990s, when the broadcaster’s influence spread from Singapore and Malaysia to South Korea, Taiwan, and the Chinese-speaking communities all over the world.

TVB’s news was once the city’s authoritative voice, the one that everyone trusted. From reports on the negotiation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration (which handed over the city’s sovereignty from Britain to communist China) to the 1989 Beijing student movement that led to the June 4 Tiananmen massacre, TVB news was Hong Kong’s main source of information.

I recall the times when the 1989 Chinese student movement was at its peak. My family would tune in to the TVB newscast as soon as it started and leave the TV on, just in case there were any special news bulletins on the latest developments. I was too young to comprehend adults’ discussions about politics, but my father recorded the newscasts on our VHS recorder. “This is history,” he said at the time, “for you to watch in future.”

The TVB of the past is the collective memory of Hong Kongers.

But this is no longer reality. My mother began to question TVB news in October 2014, when the city was at the height of the “Occupy” protests, dubbed by some the Umbrella Movement. Tens of thousands of demonstrators flocked to Admiralty, where the government is headquartered, and at the busy shopping districts Causeway Bay and Mongkok. They occupied the streets for 79 days demanding universal suffrage, without Beijing’s screening of candidates.

My mother was well aware that the current government, led by chief executive Leung Chun-ying, had not been listening to the public outcry for democracy, or demands for policies that could benefit local communities. But, like many of her generation, she does not support movements that cause a social disturbance. Still, she stayed caught up on the latest happenings by watching the news.

What caught her attention was a news report about seven police officers beating up protestor Ken Tsang. TVB news caught the act on camera and the report was aired.

However, in later newscasts, the shocking footage was edited and the reporter’s narration altered, in an attempt to dilute the impact of the police’s brutality. Footage of Tsang being beaten was cut, and a narrator said officers were “suspected to have used excessive force.” My mother wondered why TVB news had to make such changes. To find out what was really happening, she began to also watch the other news outlets, such as those found on pay-TV.

News coverage of a recent event—the Mongkok riots—compelled my mother to turn off TVB entirely.

On the first day of Lunar New Year, violent nighttime clashes broke out between police and protesters. The latter claimed to be protecting the interests of unlicensed fishball and street food hawkers trying to make a few extra bucks during the festive season. Protesters attacked the police, throwing bricks at them, and the police fired two gunshots into the air (a completely extraordinary response in a city where crime is incredibly low and no one carries a gun but triads).

I was watching the news with my mother. To my surprise, she questioned why more airtime was given to those who condemned the protesters than to those who questioned the underlying cause of the violence, or the government’s role in the whole saga.

She also couldn’t comprehend why, while a riot that had just broken out in a Mexican prison that left 50 dead was dubbed a “disturbance” by TVB news, the clash in Mongkok was called a “riot,” although no one died.

I couldn’t answer her questions, but I was amazed by my mother’s perceptiveness despite her education.

“Now TVB is airing news in Mandarin with simplified Chinese subtitles?” she said the other day, when she accidentally tuned in to TVB’s new digital channel J5. The channel carries newscasts in Mandarin, which I could understand as a public service in Hong Kong, just like newscasts in English. But the subtitles? “When did TVB think we read simplified Chinese?” she said.

That’s true. In Hong Kong—as well as in Taiwan and Macau—we use the original form of Chinese characters, not the simplified ones that were arbitrarily created by the Chinese Communist Party.

As a result, my mother has switched to pay-TV news channels. Today she gets her information from Now TV. She pays some HK$200 (US$26) a month for the privilege.

But this shouldn’t be the case.

Fair and accurate news reports should be available to the general public for free. That is the responsibility of a free-to-air broadcaster like TVB, which has been granted a spectrum license that makes it accessible to nearly all citizens living in Hong Kong. That role is especially important at times like these, when citizens have lost faith in the government’s determination to protect Hong Kong’s freedom and the rule of law.

If this self-censorship of Hong Kong’s Cantonese news broadcasts creeps into pay-TV too, my mother may have no choice but to switch to the internet for her news. And that will only be good as long as information in Cantonese still flows freely in Hong Kong.