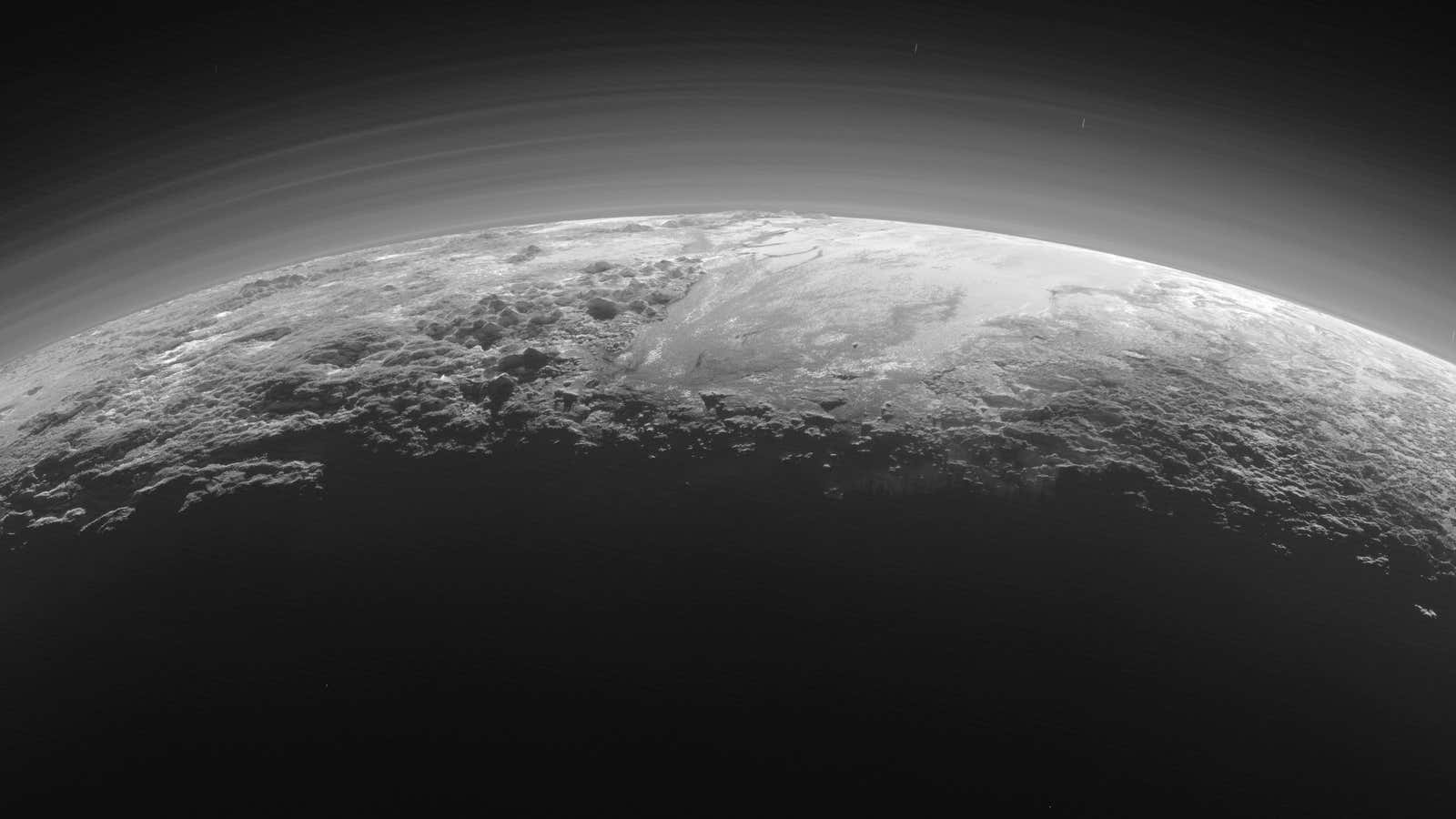

When the magnificent image above of Pluto came out in September, it took a while for scientists to notice something peculiar about it.

It’s not easily visible to the naked eye. But then, Will Grundy of Lowell Observatory told the New Scientist, scientists noticed some “localized low-altitude features” (see arrows) and “bright cloud-like things” (see circle).

Let’s look again after adjusting the contrast and zooming in:

You can see “an extremely bright low altitude limb haze … on the left” and “a discrete fuzzy cloud seen against the sunlit surface … on the right,” John Spencer at Southwest Research Institute pointed out to the New Scientist.

Those clouds are still speculations, but the possibility that the dwarf planet has a weather system has many scientists in a tizzy. If proven, these clouds could be the excuse needed to reinstate Pluto to the status of the ninth planet of the solar system. It was demoted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to be a dwarf planet in 2006.

In a study soon to be published in the journal Science on the atmosphere of Pluto, scientists mention clouds only in passing. We don’t even know what the clouds are made of (though presumably it’s a mixture of things that make up Pluto’s atmosphere: nitrogen, methane, acetylene, ethylene and ethane.)

According to the IAU, a full-fledged planet must: circle the sun without being some other object’s satellite; be rounded by its own gravity; not be so big to undergo nuclear fusion like a star; and clear its neighborhood of most orbiting bodies. It is on the final measure that Pluto fails, because it is surrounded by objects from the Kuiper belt.

But IAU’s definition of a planet remains controversial. Alan Stern, head of the New Horizons team, defends Pluto’s planetary status. He told the New Scientist that the possibility of clouds and a weather system certainly makes the case stronger.

In a previous interview with Space.com, Stern explained his skepticism of Pluto’s demotion:

It shouldn’t be so difficult to determine what a planet is. When you’re watching a science fiction show like “Star Trek” and they show up at some object in space and turn on the viewfinder, the audience and the people in the show know immediately whether it’s a planet, or a star, or a comet or an asteroid. And that’s at a moment’s notice. They do not need to know things like, “What else is around it? And, let’s see, we’re going to integrate orbits, we’re going to find out if it’s cleared its zone, or it might some day, or maybe it could but it didn’t.” That’s making something hard out of something easy, and it reflects poorly on astronomy and astronomers.