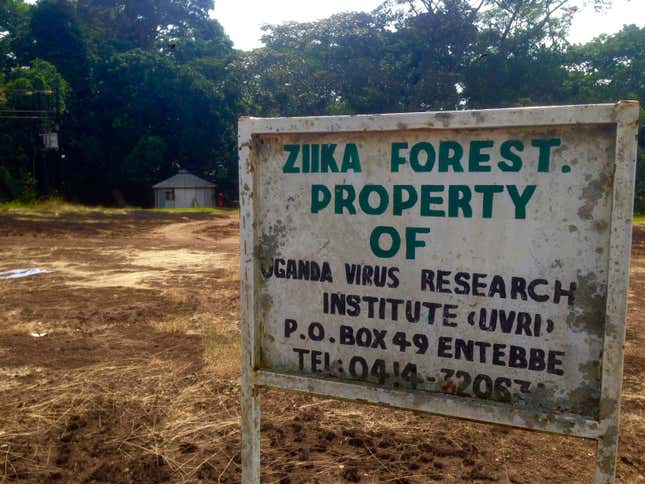

Zika Forest, Uganda

The forest where Zika virus was first identified in 1947 is located near a swamp, 25 km (15 miles) away from the Ugandan capital, Kampala. A sign at the entrance reads: “Ziika [sic] Forest, Property of Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI).”

“See that platform there?” Julius Lutwama, the head of UVRI’s arbovirology department, asked. He was giving me a tour of the 25-hectare (62-acre) tropical forest and pointing at wooden platforms high up in the trees. “In 1947, when researchers were looking for yellow fever, they would put monkeys in cages on one of these platforms. Periodically, they would collect blood samples from them and analyze them. That’s when they isolated a new virus on a captive rhesus monkey, which was not yellow fever.”

This new virus was named Zika, after the forest.

The origin story

“Nobody knows where it first came from,” the 56-year-old specialist said. “It has been in many forests for ages, from West Africa to East Africa and in Asia. The only thing that happened is that it was first identified in Uganda in April 1947.”

Since it was discovered, there have been small outbreaks of Zika in Africa and Asia. But the virus seems to have remained in those regions for nearly 60 years.

Then in 2007, a Zika outbreak occurred on Yap island in Micronesia in the Pacific Ocean. It was the first time the virus had been reported outside its usual geographical range. How did it get there?

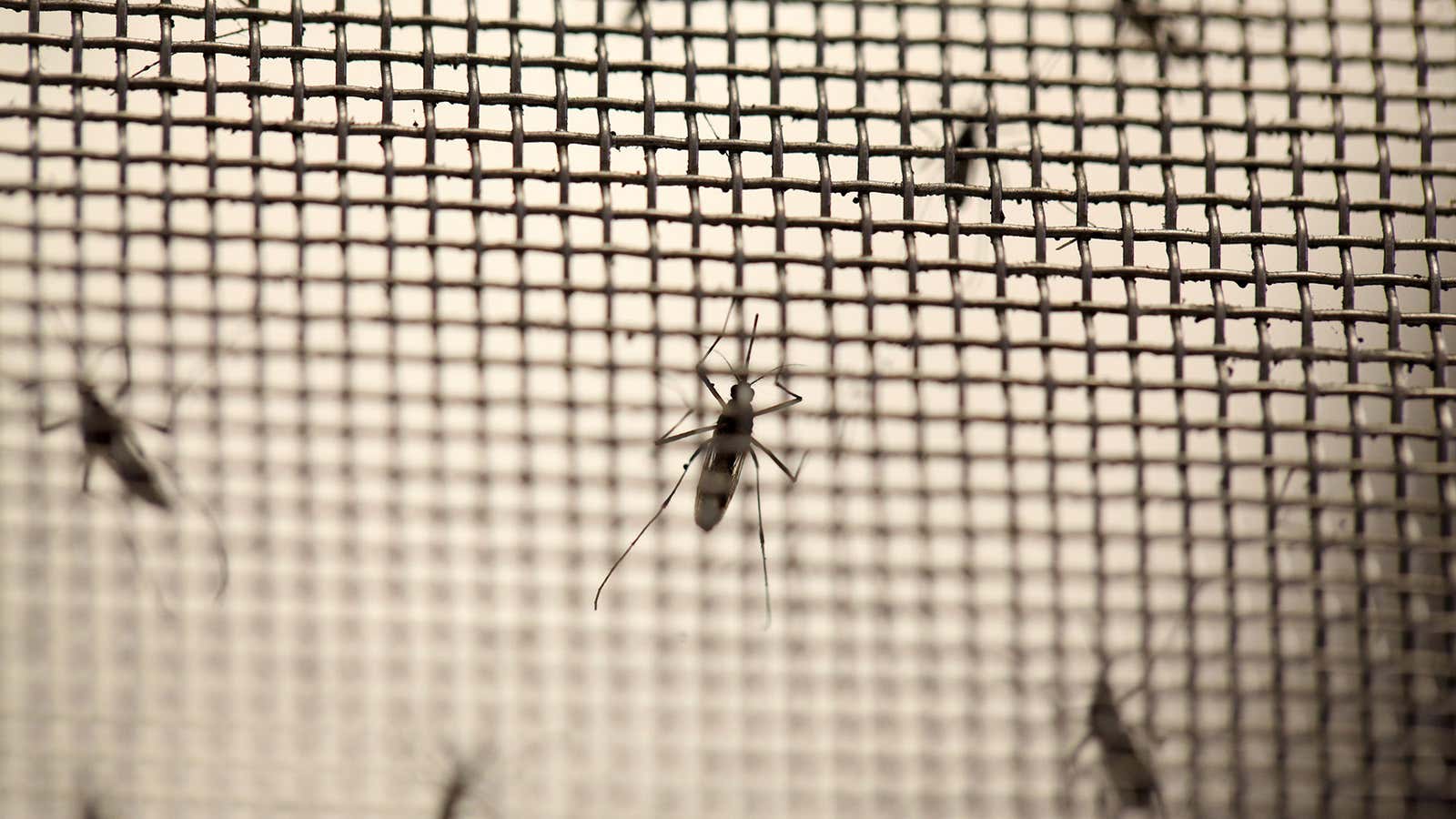

Zika virus is spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. These can’t fly more than about 400 meters (1,300 feet), according to the WHO. They need human intermediaries to take the virus farther. One way it can travel is through the transportation of infected mosquitoes’ eggs.

“For instance, in Micronesia, people fish a lot because they live on islands,” Lutwama said. And, in fishing boats, there is often stagnant water in which A. aegypti mosquitoes lay their eggs. So one likely scenario is that mosquitoes’ eggs arrived somehow in Micronesia from a Zika-infected Southeast Asian country. Then, as boats moved from one island to another, they may have carried infected eggs, which probably kicked off an outbreak on the islands.

In 2013, another outbreak was reported in Polynesia. “Experts believe that boat races facilitated the spread of Zika from Micronesia to Polynesia,” Lutwama said.

The other route the Zika virus can take is to travel in infected people. Only about 15% of people who catch Zika show symptoms, so they may easily spread the virus unknowingly. That happens when an infected person travels to a Zika-free area and gets bitten by a mosquito, which then begins a new cycle of infection. (It’s also possible, though still uncertain, that Zika may in rare cases be transmitted through sex and blood transfusions.)

The strain of the Zika virus behind the current outbreak, which began in Brazil and has spread to more than 55 countries and territories, comes from Southeast Asia, according to Lutwama. A genetic analysis in March revealed that Zika may have been circulating in Brazil since 2013, but nobody knows why it took so long for the outbreak to begin.

Naïve communities

Until the Brazilian outbreak, the disease wasn’t considered much of a threat. “Even when the outbreak occurred in Micronesia in 2007, the response was slow,” Lutwama said.

Most infected adults recover after a bout of rash or fever. In February of this year, however, the World Health Organization (WHO) was forced to declare the outbreak a public health emergency, because there seemed to be a nasty side to Zika. Since then, scientists have confirmed that the Zika virus can, albeit in rare cases, cause serious birth defects and neurological disorders.

The 2007 outbreak occurred on islands with “naïve communities,” Lutwama explained—naïve not in the sense of being ignorant, but of being medically susceptible. Zika is a member of the flavivirus family, which also includes dengue, chikungunya, and yellow fever. When a flavivirus infects you, it triggers the creation of antibodies that also make you partially immune to other flaviviruses. “So that, when another virus from the same family gets into your body, it does not affect you as much,” says Lutwama. Micronesians and Polynesians were “naïve”—they had never been infected by any flaviviruses, and thus had none of these antibodies.

Still, that doesn’t explain Zika’s rapid spread in Brazil, where the population has been exposed to dengue for many years. According to the UVRI specialists, mutations to Zika may have made it spread more easily in the Americas. Though other researchers have floated the theory too, it has not been confirmed yet.

Africa’s defenses

New Zika cases have been reported in Cape Verde, off the west coast of Senegal, since October. There have also been cases of travelers carrying Zika to the continent, but no other African country has had known cases of local transmission. The Zika forest experts seem confident that the infection will not spread too widely in Africa.

A. aegypti mosquitoes are divided into two groups, the UVRI entomologist Martin Mayanja explained. The first type breeds in forests and prefers to lay its eggs in natural bodies of water rather than artificial ones. It also prefers animal blood. The second is good at transmitting the virus to humans, partly because it prefers human blood and also because it breeds not in swamps but in containers of clean water, such as water tanks and flower pots, in or near human homes.

“These highly competent transmitters are dominant outside Africa,” Mayanja maintains. That fact probably explains why there are so few Zika cases recorded in Africa. While A. aegypti is found in Uganda, other mosquito species such as malaria-carrying anopheles are more common.

Equally, however, Uganda might have few Zika cases because not many people are tested for it. That is why Mayanja adds that, “We are [still] at risk because the world has become a global village. We have around 224 species of mosquitoes in Uganda. We do have to keep a close watch on them to know what kind of mosquitoes we have in the country and in what proportion.”