Poland’s trendy milk bars are a poignant reminder of its time under communism

WARSAW, POLAND

WARSAW, POLAND

“Look around,” said Lucas Skurczyński, a 33-year-old Protestant theologian. “There is a mix of people. No newspapers. People don’t linger. This is Polish fast food.”

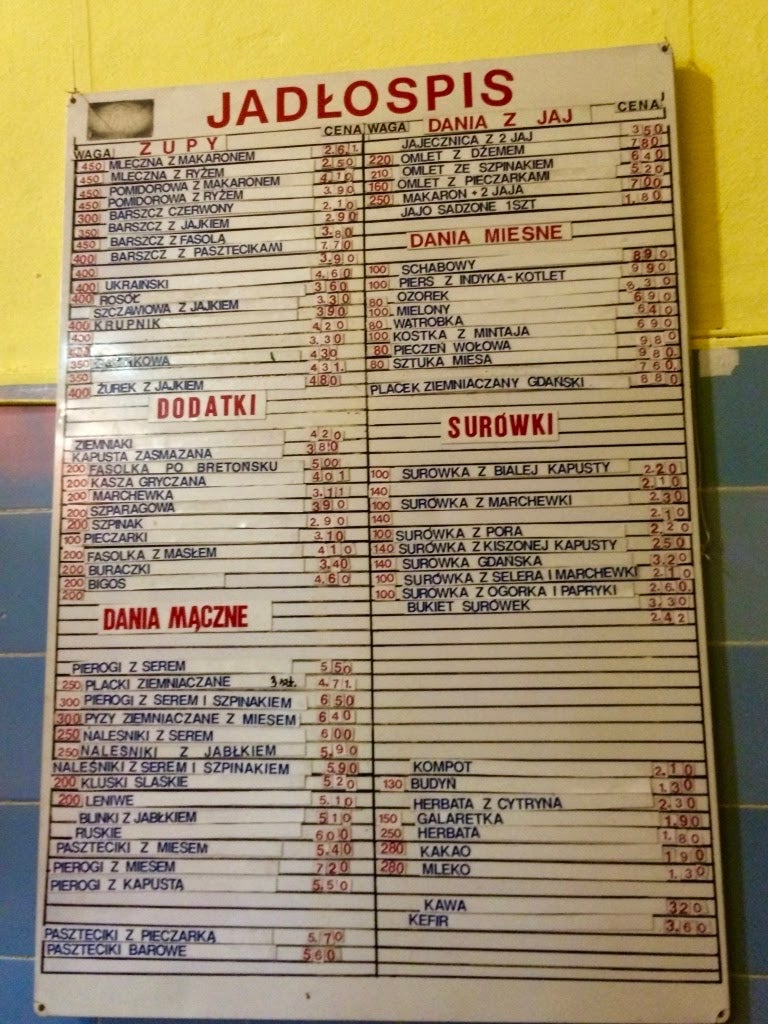

While polishing off a plate of mushroom and cabbage pierogi, Skurczyński was trying to explain to me why, after being in decline for decades, milk bars are experiencing a revival. Skurczyński, who is also a gay rights and Green party activist, is a rare breed in this mostly Catholic, conservative country. But at 4pm on a recent Monday, he fit right into the scene at Bar Bambino near Warsaw’s center, where students and government ministry workers coming from classes and offices mingled alongside pensioners. An extensive menu of low-priced, traditional Polish fare hangs on one side of the long, narrow, wood-paneled eatery and an oversized painting depicting a medieval forest scene on the other.

Less than 150 milk bars exist across the country today, down from 40,000 in their heyday when Poland was a communist state, says Agnes Sofie Nowicki, who wrote her master’s dissertation on milk bars. “They are a part of Polish history,” she told me over the phone from her home in Zürich, Switzerland.

Milk bars are more than a century old, rooted in urban dairies—hence the name. After WWII, when Poland was a Soviet satellite, milk bars became state-subsidized, self-service cafeterias where workers could get a cheap, hot meal outside of their homes. Subsidies, which continue to this day, cover basic ingredients like dairy products, vegetables, and flour—and dishes are mostly vegetarian. Despite the fact that they are called “bars,” no alcohol is served.

While the current conservative Polish government has been shrinking the subsidy, a finance ministry spokeswoman said in an email that they still remain a tool to help low income people get inexpensive food. Last year the milk bar subsidy covered 40% of the price of raw materials, and a proprietor’s profits were capped at 56%, according to ministry. This year the ministry says it has cut the subsidy by more than a quarter to 14.7 million zloty ($3.8 million).

Immediately after the fall of the Iron Curtain, milk bars began closing. As the country took to capitalism, Poles embraced international chains and modern dining. Milk bars, with their grumpy service and no frills interiors, came to symbolize privation during decades of communism, and for a while, they became a source of shame for Poles. (A famous scene from a 1980s Polish movie takes place in a milk bar where cutlery is attached to chains and plates are screwed to tables to keep them from being stolen.)

But today they’re trendy, especially among younger people unburdened by Poland’s communist past. “Before, people didn’t have a choice of what to eat, and now they do,” said Nowicki. “That gives milk bars a completely different feeling,” she said. “For young people who never knew socialism, it’s an adventure to wait in line, order at the cash register, find a place to sit among the crowded tables, and wait for your food to be called.”

“There’s a surefire way to tell real milk bars from modern copy cats,” says Nowicki, who grew up in Germany with a Polish mother. Traditional milk bars have prices in odd numbers because the state subsidizes a percentage of the ingredient price, and these savings have to be passed on to the customers. So for example, a tomato soup could cost 2.69 zloty (68 cents) depending on the price of the tomato and the percentage of the subsidy. Every time a milk bar owner buys groceries, they change the price on laminate board menus. Fake milk bars, by contrast, round prices up and keep them constant.

Skurczyński and I head over to Bar Gdański, across a two-lane thoroughfare from his apartment. It’s dark as we walk, and icy flurries prick our faces. Inside an elderly lady, still wearing her black furry hat and coat, is hunched over her supper. Today a plate of potato pancakes cost 4.71 zloty ($1.18). Skurczyński tells me that he can smell the cooking on his way to work before 7am in the morning. When we walk inside, a worker comes over to shoo us out. We’re closing for the day, she says in Polish. Come back tomorrow.