Inside the Trump machine: the bizarre psychology of America’s newest political movement

Over the span of three days in March, in far-flung corners of Ohio, more than 20,000 people—retired schoolteachers, hair stylists, chinos-clad Young Republicans, Nicaraguan immigrants, Vietnam vets, primly coiffed soccer moms—braved downpours, traffic, muscle spasms, hunger, and protesters for a chance to behold, in the very tanned flesh, Donald J. Trump, billionaire, business genius, TV star, and, very possibly, the next president of the United States. One of those people was me.

Over the span of three days in March, in far-flung corners of Ohio, more than 20,000 people—retired schoolteachers, hair stylists, chinos-clad Young Republicans, Nicaraguan immigrants, Vietnam vets, primly coiffed soccer moms—braved downpours, traffic, muscle spasms, hunger, and protesters for a chance to behold, in the very tanned flesh, Donald J. Trump, billionaire, business genius, TV star, and, very possibly, the next president of the United States. One of those people was me.

I went, first and foremost, to answer a deceptively simple question: How has Trump defied pretty much every rule not just of electoral politics, but of contemporary civil discourse to lead the race for the Republican party’s nomination for president? Set aside for one moment the economic conditions that we know have made Trump’s ascent possible. What about those of the human psyche? What does Trump’s improbable rise reveal about how Americans understand themselves, what they imagine for their country, what they crave in their leaders?

To find answers to these questions, I decided to become part of Trump’s audience, not just its observer. For three days in mid-March, I buried my reporter credentials in my bag and lost myself in the throngs of Trump supporters at rallies in Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Youngstown. What I experienced astonished me. I’m far from being a Trump supporter; in fact I object to most of his views. But as I shuffled out of a Youngstown aircraft hangar, I became aware of the unsettling but very real possibility that, in the thrill of the moment, I’d been chanting along with the Trump crowd. (I don’t think I did, but I can’t be sure.) Indeed, it felt like I had just taken part in an epic psychological experiment.

Spending three straight days in the audience taught me one crucial thing. The overlooked star of the Trump show is the crowd—the single-voiced creature that roars ”Mexico!” when asked about wall construction, and emits a foghorn of boos when reminded of reporters cooped in a pen at the rear of the room. From within the Trump rally masses, I felt the strange sea-change that turns 20,000 individuals into one being, I felt its power swell, and sometimes it felt good.

I was also a part of this crowd when it morphed once again, at a rare town hall event that Trump held in Cincinnati. As he flubbed audience questions, the spell fell away, and the crowd fractured into a few hundred distinct individuals in folding chairs. Trump’s struggle to connect one-on-one hinted at how vital big crowds are to his legendary charisma. His relationship with the crowd is why Trump is ever so close to becoming the Republican nominee. Though he seems to have mastered mind games that let him draw energy from the crowd, the relationship is reciprocal. In his stump speeches, Trump brought to life a vision for America his supporters long for, and begrudge mainstream culture for blotting out. Fueling Trump’s unforeseen success is the power he promises the crowd in return: That they can make the America of their imaginings a reality.

The Trump Show

A Trump event begins with the wait. At the events I attended, fans had to line up hours before the event in order to guarantee themselves a place in the audience, and then wait hours more inside. To get a good spot, the wait ran around five or even six hours when you account for the fact that Trump was a minimum of 45 minutes late to each. And that’s just the average; during the town hall in Cincinnati, a man announced to Trump that he loved him so much he’d waited in line for 17 hours.

Then there’s the discomfort that accompanies the wait. During the couple of hours audience members line up outside—this time is necessary for security to sweep the premises after the media sets up its cameras, says the campaign—they usually lack access to food, drink, and bathrooms. (Those worried about the lack of facilities mentioned that they’d simply stopped drinking altogether a few hours back).

Things generally don’t get much better once inside. Two of the three venues I went to had nowhere to buy food, and only one had seats. The Youngstown hangar—the serendipitously named Winner Aviation—had no water. Many in the crowd—a major share of whom were aged 40 and over—complained of swollen ankles, backaches, and light-headedness. Still, the atmosphere was upbeat. In fact, the warmth and camaraderie I felt while chatting with those nearby surprised me. Sometimes this casual friendliness was downright touching—like when the woman next to me in Youngstown gave me two packets of Smarties after she heard me absently grumbling about hunger.

Defining “us” and “them”

Trump’s security and clearance measures are consistently more rigorous than those of any other candidate, including former first lady Hillary Clinton—at least in my experience. Regardless of venue size, audience members must pass through a metal detector gate and a wand search. Inside the venue, Secret Service agents abound.

Both the violence that broke out after Trump cancelled a Chicago rally and the protester who tried to storm the stage at a rally in Dayton suggest this rigor is necessary. However, at the scores of other events, the main duty of Trump’s security force seems to be spotting and removing protesters from the premises. As the rally start time nears, security agents, including secret service officers and local police, fan out amongst the audience. Standing at short intervals from each other, with their backs to Trump’s dais, the agents methodically make eye contact with people in the audience in order to check for interlopers (or so one police officer told the group around me in Cleveland). The effect unnerved me, but Trump supporters seemed unfazed.

Critics of Trump’s TSA-on-‘roids approach to crowd management tend to focus on the punitive zeal he inspires—his incitements to violence, the now infamous sucker-punch, his campaign manager’s alleged manhandling of a protester, and other less bloody kerfuffles. However, the effect of Trump’s security strategy on the crowd even when the protestors aren’t there is just as notable.

The people I spoke with were genuinely scared of violent protesters. They debated whether it was even safe to be there. Several women I spoke with mentioned that they were so afraid that a protester might hurt them that they almost didn’t come. Others spoke of friends who had wanted to bring their children, but deemed the event too unsafe. In Cleveland and Youngstown, women I was chatting with worried that Trump might be assassinated. When someone noted that he wears a bullet-proof vest, the “phews” were many and audible.

Just about everyone was on the lookout for protesters. As audience members whiled away the hours looking up the latest poll data and trading bitter quips about the Republican establishment, they also scanned the audience for out-of-place characters, chatting about their suspicions with their neighbors.

In Youngstown, I was drawn into a discussion with a few people around me about an older man in a Hillary t-shirt just to my right. For 10 minutes, we debated whether alerting security was worth running the risk of offending the guy. Eventually, someone straight-up asked him. His shirt, it turned out, suffered from a design flaw: In tiny font under the huge “Hillary” plastering his gut, it read “for Prison.” The chary camaraderie that had built up gave way to hilarity and mock horror at having almost ratted him out to the Secret Service. After the giggling subsided, this particular group (myself included) continued to chat for the next three hours, posting pictures with each other to Facebook.

Remarkably, that vigilante farce happened before the human “Trump!” alarm system was switched on. At each rally, about an hour or so before Trump is scheduled to take the stage, an automated voice (that sounds weirdly like rival Ted Cruz) instructs attendees not to touch the protesters and to alert security to their presence by chanting “Trump! Trump! Trump!”

At this, the crowd became even more hawkish about spotting protesters. Those who found protesters in their midst thrust up their signs and, to drown out the protesters, bellowed “Trump! Trump! Trump!” as instructed. Everyone else craned their necks to see where the “Trump!” alarm came from, many of them snapping photos from overhead in the hopes of documenting the action. After Trump had begun talking, every time the human “Trump! Trump! Trump!” alarm sounded, the candidate himself had to pause and wait for it to die down, usually throwing in a “get ’em out of here,” as if to keep the rest of the crowd engaged.

The disconcerting presence of the security agents ratchets up the drama even more. In Youngstown, for instance, five or so agents pushed their way to the front of the crowd, encircling a patch of audience members at the edge of the barricade, just beyond Trump’s podium. I found myself scanning the crowd to see what attracted them, and noticed others doing the same. Nothing ended up happening, but for 15 minutes in the middle of Trump’s speech, my adrenaline sure was pumping.

Mind games for the masses

The peculiar intensity these circumstances create is almost certainly not a coincidence. (At time of publishing, Trump’s campaign had not responded to Quartz’s request for comment.) Intentional or not, the format of Trump events involves classic techniques for galvanizing masses, say experts on crowd psychology whom I consulted afterward to discover what on Earth I had experienced.

For starters, making people wait is “a pretty standard technique,” says Stephen Reicher, professor of social psychology at the University of St Andrews and a pioneer in the study of crowd psychology. It’s an assertion of power (“I am such an important thing, you have to wait for me”). It also draws on the feeling that if you’re waiting this long, the experience must be worth it. And it establishes a sense of who the “true believers” are. Though possibly not deliberate, the discomfort of the wait too has its purpose: The shared sense of self-sacrifice reinforces the experience’s value.

“In many cases, suffering for the cause is critical to having a sense of belonging. We have found this in pilgrimages, in football fans, in people attending rock concerts,” says Reicher. “Suffering is what sorts the wheat from the chaff. So when the event finally occurs, there is a sense of intensified shared identity (‘we are all true believers and all in this together’), and a sense of getting something which is truly valued—both sources of positive affect.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s pumped-up crowd control strategy does more than simply silence protestors.

“Surveillance and security are critical ways of delineating ‘us’ and ‘them.’ For insiders, the security is not experienced as targeted at ‘us’ but as protecting us from ‘them.’ It is protective rather than oppressive,”says Reicher. “But, of course, it equally sets up a notion of us as under threat, of outsiders as dangerous.”

That feeling of being in danger and under threat intensifies the shared identity that forms among supporters, he says.

Alexander Haslam—an expert in crowd psychology at the University of Queensland and, with Reicher, co-author of The New Psychology of Leadership: Identity, Influence and Power—says he too gets “a strong sense of the theater of all this.” And it’s not just Trump or his stony-faced security forces who are performing: This is interactive.

“[W]hat these unfolding dynamics do is allow people to live out their shared identity in very dramatic ways,” says Haslam. “Thus we don’t just talk about rooting out the enemy, we actually do it.”

As Haslam notes, the campaign benefits from this thrill of protester-hunting and the entertaining exchanges that follow. At the Cincinnati rally, Trump even admitted as much:

“We had one yesterday where we had seven or eight incidents where [the protesters] stand up and everybody shouts ‘em down and, you know, it’s fine. Honestly, in certain ways, in certain ways, it makes it more exciting. To be honest. It does. Makes it more exciting. We might have a couple of more.”

Just like us, but with a jet

When it’s finally getting time for Trump to take the stage, the crowd is hungry, tired, giddy, and on edge. One question in particular tends to be on their minds: ”Has Trump’s plane landed yet?”

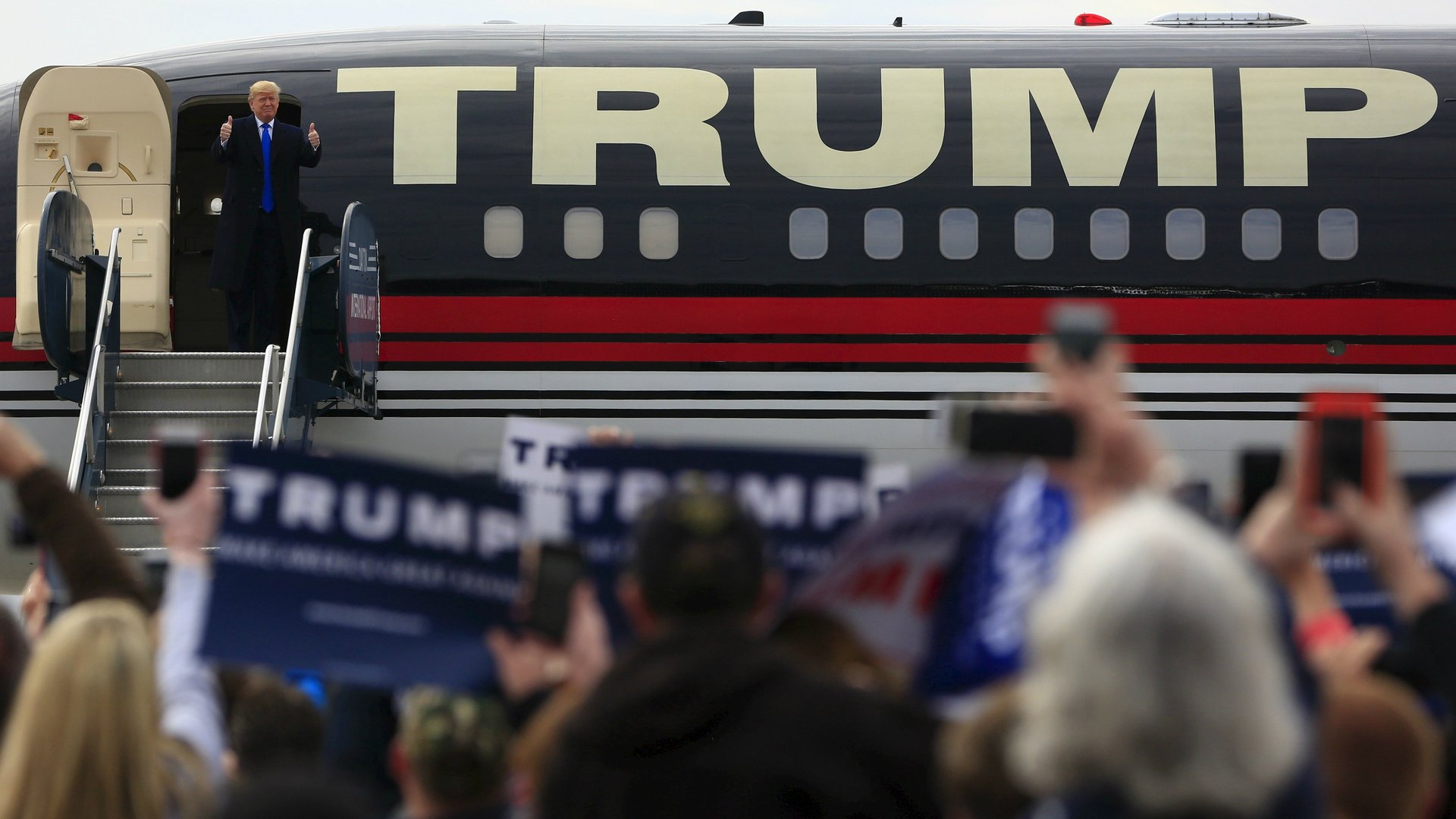

Unlike his competitors, Trump can zip around the country in his private jet, a Boeing 757. But there may be another reason besides convenience why many of his campaign stops are in or adjacent to airports: People love his plane. In Cleveland, audience members watched footage of his private jet’s descent on their phones while they waited. After the event ended, a few people drove off, but the majority stood on the runners or hoods of their cars to catch a glimpse of the Trump plane’s takeoff. “There he goes!” people cried as the jet’s silhouette pierced the blue. The campaign seems aware of the plane-awe; the Trump plane has been known to do fly-bys on occasion.

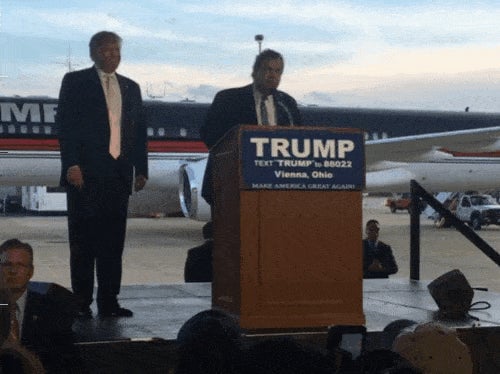

Trump’s rally in Youngstown made it clear what all the fuss was about. The plane slid into view in front of a giant American flag while the fanfare opening of the Air Force One theme song blared. In the distance, the just-setting sun lit the clouds in purple and pink. As if to let the crowd take in the entrance’s epic scale, Trump let the suspense build for another six minutes. Finally, the music cut to the surreal arpeggios of Alan Parsons Project’s “Eye in the Sky,” the plane’s door jerked open, and first New Jersey governor Chris Christie, then Trump himself emerged.

Hours later, as the crowd filed out that night, I overheard some men chatting. ”Do you think Trump will even want to ride in Air Force One once he’s president?” asked one man. “Or do you think he’ll just keep riding his own jet?”

The plane is only the most obvious way Trump flaunts his wealth. Suits are another. While other candidates don jeans and half-zip sweaters to seem down to earth, Trump heads full-tilt in the opposite direction. On the campaign trail, he’s seldom seen in anything but a dark suit, roomy and unbuttoned. Even when sweat is pouring off him, he never removes his suit jacket. Almost always a tie, often a red one (one fashion critic suspects he keeps his jacket open to emphasize the “virility” of his ties).

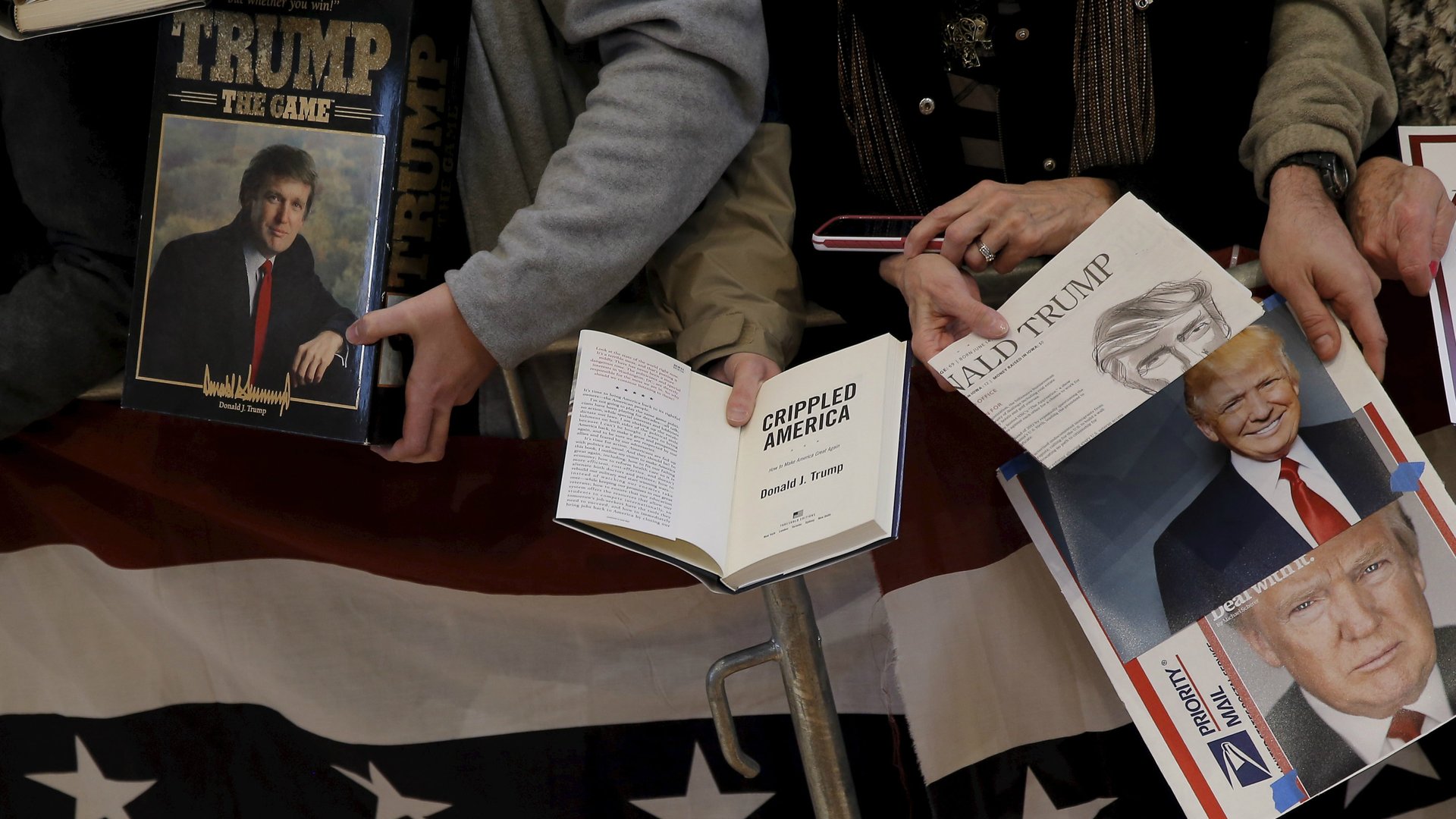

Trump’s books, too, sometimes function as totems of his managerial genius. At every rally, people toted The Art of the Deal, Crippled America, and his other books around, sometimes waving them in the air as they chanted (unaware, most likely, of the other leader whose followers waved his books at him).

Permission to “be real”

Though Trump’s glitz was on full display at the Ohio rallies, many of the supporters I talked to somehow still saw him as a “regular guy.” This baffled me for a while. In the same breath as they gushed about his taste for gold plating, his fans also claimed him as one of their own.

Yet it’s these trappings of wealth that transmit a sense of Trump’s uniqueness—which Haslam said is crucial to his success.

“Rather than look like ‘any other’ politician he goes to great lengths to cast himself as different from other politicians and to defy categorization in standard terms,” he said. “This is also part of his apparent authenticity as a leader.”

Plus, Trump is only different from his typical supporter if you view the world through the prism of net worth. For his fans, though, that’s not where the rift lies, says David Livingstone Smith, author of Less than Human and founding director of the University of New England’s Human Nature Project.

“The interesting thing about Trump is although he is very rich, people feel a kind of class kinship with him—in other words, he’s not an elite. He speaks in a way that resonates with a certain sort of person,” says Smith. “There are certain things he can say that everyone really believes that the other politicians can’t say—for instance ‘I played the game, I gave money to these politicians to get them to do what I want.’ None of the other politicians can say that. I think that really resonates. They feel something profoundly authentic about Trump.”

Trump’s rivals struggle to prove their “ordinary guy” bona fides by looking the part. Trump doesn’t have to. His ordinary-ness comes from how he connects with a certain swath of Americans on a much more fundamental level: their world view.

“He says the same things we do around our dinner table,” a retired schoolteacher from Warren, Ohio, told me at the Youngstown event. “He’s not afraid to say the things that everyone knows are true, but that we’re not allowed to say in public anymore.”

In line as friendly bonds cemented, I heard lots of similar statements—that Trump is ”taking down PC” (meaning, “political correctness”), that he “talks like us,” that he’s willing to speak the truth by using terms like “anchor babies.” By rejecting PC culture so vociferously, Trump is “tapping into passions that have been lying latent in certain portions of the American psyche,” said Smith.

“There’s been a kind of inauthentic going-along with being anti-racist, anti-sexist, and so on. But people in the privacy of their own homes don’t really accept these things,” says Smith. “Trump, I think, is giving permission for people to be real. And that’s really powerful.”

Trump and the H-word

Since announcing his candidacy a little less than a year ago, Trump has drawn more censure and vitriol than any other candidate. What sets these assaults apart in modern politics is that they come from deep within both parties, alarmed and—in the case of the Republicans—panicked over the ramifications of a Trump presidency. A frequent charge is that Trump resembles some of history’s vilest demagogues—particularly Hitler—with the implication that, like them, he could unleash dangerous racist policies with an unknown but ominous outcome. (To be fair, president Barack Obama and Cruz, and other politicians, have been subject to similar charges.)

“A lot of times when people compare Trump to Hitler, it’s really contentless. It’s simply a way of disapproving of Trump,” says Smith. “I’m not saying Trump is Hitler or Mussolini. Trump is Trump.”

And yet, the way Trump controls his crowd’s moods—which may be instinctive—hews closely to propagandist formulas that, not so long ago, swept Germany along in its drift toward extremism.

“Some of the rhetorical moves Trump makes are extraordinarily similar to the ones Hitler made,” says Smith.

The psychology of propaganda

The parallels between Trump and Hitler lie not in the content of their speeches, but rather, in their shared rhetorical style, the emotional response they elicit, and their powerful relationship with their crowds.

Smith points to what he calls a neglected 1941 work by a British psychoanalyst named Roger Money-Kyrle, who spent four years in Vienna undergoing psychotherapy with Freud in the 1920s. During that time, he went to Germany to see Hitler and Goebbels speak at a rally. In a paper called “The Psychology of Propaganda,” Money-Kyrle describes the mechanisms of what he saw:

“To me, at least, the speeches themselves were not particularly impressive. But the crowd was unforgettable. The people seemed gradually to lose their individuality and to become fused into a not very intelligent but immensely powerful monster… under the complete control of the figure on the rostrum. He evoked or changed its passions as easily as if they had been notes of some gigantic organ. The tune was very loud, but very simple. As far as I could make out, there were only three, or perhaps four, notes; and both speakers or organists played them in the same order.

For 10 minutes we heard of the sufferings of Germany… since the war. The monster seemed to indulge in an orgy of self-pity. Then for the next 10 minutes came the most terrific fulminations against Jews and social-democrats as the sole authors of these sufferings. Self-pity gave place to hate; and the monster seemed on the point of becoming homicidal. But the note was changed once more; and this time we heard for 10 minutes about the growth of the Nazi party, and how from small beginnings it had now become an overpowering force. The monster became self-conscious of its size, and intoxicated by the belief in its own omnipotence.”

A similar sequence—which Money-Kyrle described as first melancholia, then paranoia, and finally, megalomania—runs through Trump’s rhetoric, says Smith.

“If you swallow the first two movements, you’re feeling helpless and then frightened. And then you’re offered the fantastic package of magic to solve all your problems,” he explains. “Trump does that very, very well—I think he has a gut understanding of the psychology of persuasion.”

To test Smith’s case, I went through the many reams of observations I scribbled down reflecting on the Trump rallies. Nearly every paragraph fit Money-Kyrle’s sequence.

Melancholia

“You’re losing a plant over here,” Trump told his audience in Cleveland, stabbing at the air with a pointed finger. ”And you’re losing a plant over there. And you’re losing another plant, I hear, over there. Any direction I point to you’re losing jobs, you’re losing your plants.”

The crowd around me in the Cleveland murmured and nodded as Trump enumerated northern Ohio’s ominous economic prospects. It’s a theme he specializes in. The premise of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” campaign slogan alone—i.e. that America was once, but is no longer, great—evokes the shame and suffering of a country in decline.

Of course, this sort of gloom-mongering is often stock-in-trade for non-incumbent politicians. But Trump’s stump speech goes much further in cataloging in intricate detail the fading of America’s glory. He begins with disappearing factory jobs. The US no longer makes televisions, cars, or air conditioners, and instead buys them from other countries. The jobless rate is more than 40%, and US economic growth is “essentially zero.” By moving jobs overseas—particularly to China and Mexico—US companies are impoverishing American workers. Meanwhile, a flood of heroin is surging over the border from Mexico, along with droves of unauthorized immigrants. American airports are Third World-esque eyesores, and potholes pock the roads. The US military is stretched thin. The public disdains the police.

Above all, no one respects America. “Right now, we’re being ripped off by everybody,” Trump told the Cleveland crowd. ”We’re like the whipping post for everybody.”

Beyond his montage of industrial decay, Trump’s rhetoric reinforced a widely held feeling that mainstream culture has turned against them. People I spoke with lamented that they could no longer make common-sense observations—say out loud things everyone knows to be true—because of the need to make “other people” feel good about themselves. Whether in public or in their choice of government, said some, they no longer have a voice—a theme the campaign capitalizes on with its ubiquitous ”The silent majority stands with Trump” signs. While the Nixonian origins of the phrase “silent majority” might be lost on some supporters, the sentiment surely isn’t.

Paranoia

Who’s to blame for this suffering and injustice? Who has benefited at their expense? Trump’s favorite call-and-response routine focuses on one supposed culprit: “Who’s gonna build the wall?” he asks. “Mexico!” bellows the crowd.

Thanks to Trump’s media blitz and his mastery of social media, his supporters have become well versed in the sources of their suffering long before he takes the stage. “Mexican illegals” are bugbears who take jobs, hook Americans on heroin, and commit heinous crimes. Their presence shows that the federal government refuses to enforce America’s laws. After showing me a saved iPhone contact for “Immigration Police,” a soft-spoken young man in Cincinnati explained that he recently called it to report five illegal-looking Mexicans admiring his hood ornament. As far as I could tell, the only pin that sold completely out at any of the rallies featured a wall that read “Paid for by Mexico,” with a sombrero-wearing cartoon saying, “Si, señor.” (As of 2014, unauthorized immigrants made up 0.7% of Ohio’s population, according to the Center for Migration Studies, a slight decrease since 2010, driven by a dramatic shrinking in the state’s unauthorized Mexican population.)

People fear Muslims too. Beyond his usual rhetoric, Trump had whipped up worries by announcing over Twitter that the man who attacked him in Dayton, DiMassimo, is affiliated with ISIS. This was swiftly disproven. Trump, however, has so far refused to recant.

Another target is the Republican establishment. Trump and his supporters delighted in skewering rivals “Little Marco” and “Lyin’ Ted.” They also couldn’t get enough of trashing Mitt Romney, who had just come out against Trump—or, for that matter, the Rubio campaign’s support of John Kasich. They resented all the “backroom deals” they suspected were going on, that the Republican Party bigwigs thought they could sidestep the people. “They’re trying to steal our votes,” a man in Youngstown said.

The protesters, of course, feature heavily in the cast of rally villains too. For instance, both Trump and people I spoke with in the crowd stated that the protesters were part of a professional operation orchestrated by Bernie Sanders (or, according to a few audience members, George Soros). Trump and the supporters I spoke with vented that the protesters were trying to rob them of their freedom of speech.

One more paranoid highlight of Trump’s rallies is the tag-team maligning of the media. In every rally I attended or watched on YouTube, Trump took a minute or so to rail against the media. His remarks in Cincinnati should give you a sense of one of these tirades:

“All we want is for them to be honest. But when you have a dishonest newspaper like the New York Times you have to be able to sue them. You have to be able to do it. Because the level of dishonesty—and that’s why I talk about so many of them—but the level of dishonesty of the press is beyond belief. Far greater than you would ever think. Believe me. ‘Cause you don’t see it as much. I see it. I see it. They do stories that are so bad. That are so wrong. And knowingly wrong…. They’re less popular than politicians, which is pretty amazing when you think of it.”

Then Trump scowls at the media cattle pen in the back of the room and calls the press the “most disgusting” and “most dishonest” people he’s ever seen, pantomiming his disdain with an elaborate sneer before goading his supporters to turn and glare too. On cue, the crowd turns and boos.

As I waited with the rest of the crowd outside the Cincinnati town hall event, a man selling buttons and t-shirts bounded up to the people in line and excitedly informed us that he “almost beat up one of them.”

“One of the protesters?” someone asked.

“No, one of those media people—they tried to ask me a question,” he said, grinning and punching the air with his fist before strolling off.

Tapping into this roiling resentment is a key part of how Trump operates, says Reicher.

“Resentment is a much-understudied but critical factor in much right wing populism. The idea is that ‘they’ have taken away something that is rightfully ours. They have stolen ‘our’ America,” he says. “Trump binds people together around this core perception. He makes himself emblematic of this resentful America and promises to put people in a position where the tables will be turned and they will get their own back on the carpet-baggers.”

Megalomania

“It’s a movement!” Trump is fond of saying, surveying his crowd in wonder before adding, “I’m just the messenger.” But his flattery of the masses for their overpowering force rarely ends there. After taking the stage in Youngstown, he began:

“We have something going that people haven’t seen before. It’s really a drive, and I mean, honestly they’re talking about—it’s one of the great things that they’ve seen in political history. It’s been on the cover of Time. It’s been at the head of every newspaper. It’s really something special. We’re gonna make our country so much better. It’s going to be great again. And it’s going to happen quickly.”

Numbers soon follow; he runs through these like each rally is an earnings report—the latest polls, the magnitudes of his recent victories, how much money his competitors spent trying to defeat him.

And, of course, the size of the throngs he’s attracting, which are said to have reached 30,000. While it’s rare to draw such massive turnout so early in the primaries, it’s not unheard of. (This year, Democrat candidate Bernie Sanders has attracted similarly huge audiences, as did Barack Obama eight years ago.) What’s more unusual, however, is Trump’s obsession with crowd size.

His fans also see audience size as a symbol to the outside world of the fervor he inspires—and are anxious about what a less-than-dense crowd might imply. In Youngstown—which, in addition to being announced on the fly, involved a complicated shuttle bus arrangement—supporters I spoke with worried that he wouldn’t be able to draw a crowd big enough to fill the hangar. (They cheered raucously when Trump took the stage, crowing, ”Look at this massive crowd in this big hangar—and we set this up like, what, 15 hours ago?”)

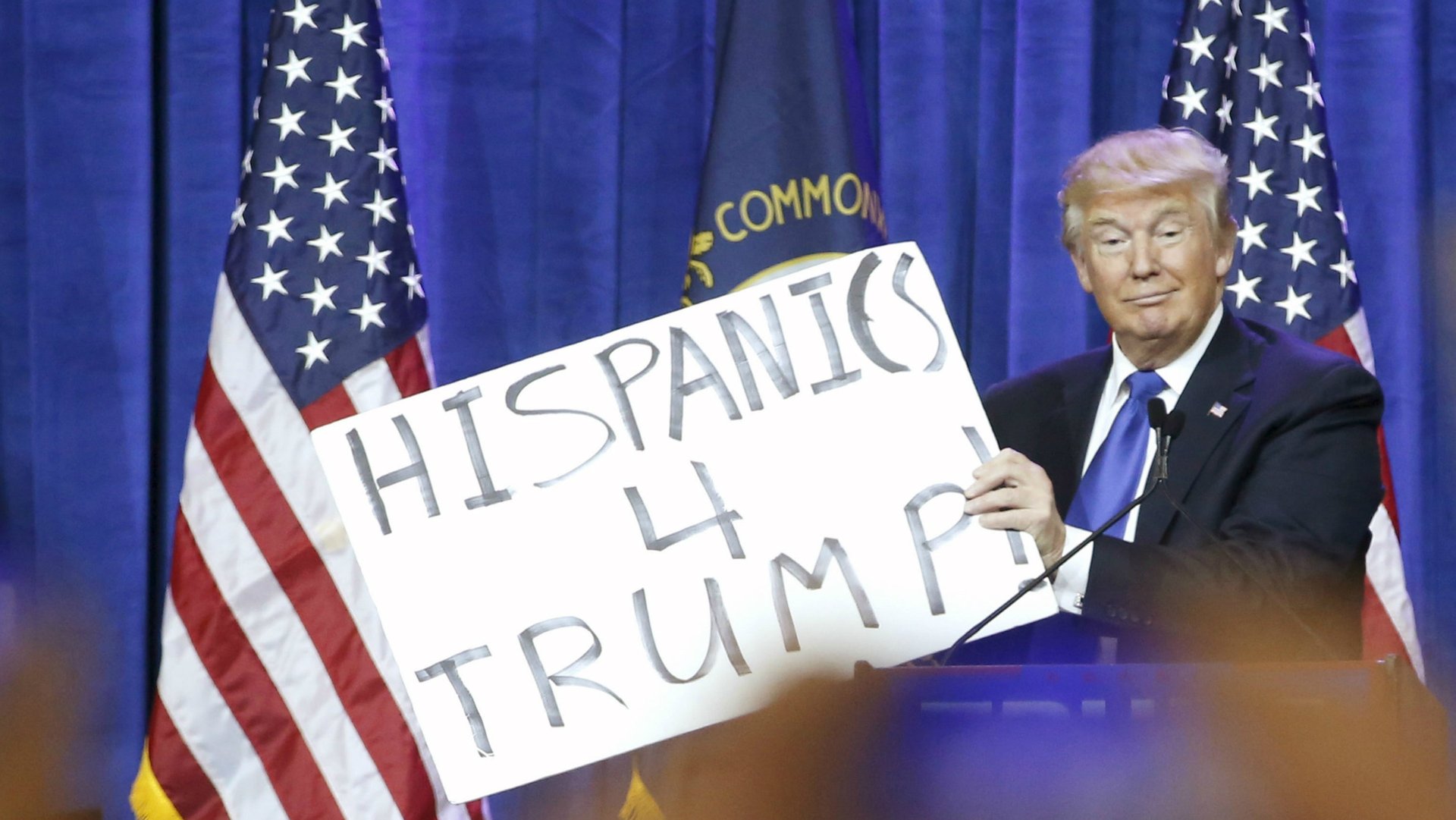

Trump and his supporters take great pride in the diversity of voters the campaign is attracting. During the Q&A session in Cincinnati, after a woman from Nicaragua praised Trump, he responded, “I’m telling you: the Hispanics. We’re going to do so well with the Hispanics. People know.” The crowd whooped exuberantly.

Lest those opportunities fail to present themselves so conveniently, Trump sets aside time in each speech to run through a demographic roll call of his supporters. Here’s what he said in Youngstown:

“So we go to South Carolina and that’s going to be Ted Cruz country—that’s Lyin’ Ted country—and we go and everybody says he’s gonna win. And who wins in a landslide? Trump…. I won with the military. I won with the vets. I won big with the evangelicals. I won big with everybody. I won with women. I won with men. I won with highly educated, I won with the less than highly educated. We won with every single category.

The presence of first-time voters seemed to pique particular pride among Trump supporters, who remarked frequently upon their rumored heavy support for Trump and cheered fellow attendees wearing homemade ”first-time voter” t-shirts.

Finally, there are Trump’s remedies to his supporters’ suffering. Building the wall. Slapping a 45% tariff on Chinese goods. Threatening multinationals to keep jobs onshore. Bombing ISIS. Or Trump’s default policy proposal, “winning.”

Trump’s Achilles heel?

Trump almost never does town hall events—strange for a person with such legendary charisma. But on Sunday, March 13—two days before the Ohio primary—in a tony events center in suburban Cincinnati, he held one. During the first half, as Trump wound the stem of his stump speech, I felt the crowd of reportedly 1,800 purr to life, booing the media on cue and leaping in human “Trump!” alarm action when two people popped into an aisle and unfolded a ratty Bernie sign.

When Trump shifted to fielding questions, however, I felt the energy in the room change. Suddenly, we were no longer the crowd; we were individuals.

The first “question” wasn’t exactly a stumper: it was a guy telling Trump, ”I love you, man.” (He wasn’t alone; five out of 18 questions were actually just expressions of adoration, two of which involved hugs.)

Then came something much trickier: A question from Keith Maupin, a local man who founded a soldier-support charity after his son was captured by Iraqi insurgents in 2004 and later killed. An older man with a white beard, glasses, and a ball cap, Maupin is something of a local hero—while in line, people kept bounding up to take selfies with him—and had been asked by the Trump campaign to attend the rally, according to a charity spokesperson. As Trump stepped down from his boxing ring-like stage to face him, Maupin asked Trump to “clarify” and “explain” his remarks made on CNN last summer in which he said that captured soldiers aren’t war heroes. “Oh no no no, I was, I never did that—you know that,” Trump interjected. After Maupin presses him again to explain his remarks, Trump told him “they are real heroes.”

Trump’s handling seemed awkward, particularly his initial denial and his insistence on throwing the question back on Maupin—a generally sympathetic character—by repeating ”you know that” throughout the exchange. Did anyone else pick up on Trump’s gracelessness, though? Maybe. “But you didn’t do what he asked…” exclaimed the Trump superfan next to me, under her breath.

The gaucheness didn’t let up. Minutes later, a nine-year-old boy asked Trump what he would do for his education. First, Trump launched into a long lecture about the need to “replenish” military equipment. Then he swerved back to the actual topic at hand, to say he’d abolish federal education benchmarks.

He then veered down a weirder path:

You around this area? We’re gonna bring the education where your mother and your father and everybody else’s parents and uncles and—they, they, they love… they love you. Do you think your parents love you? Huh? They love you. They run it with love, okay?

Toward the end of the event, Trump called on a woman to ask what was supposed to be the final question. After identifying herself as a Native American, she asked if Trump would apologize to Native Americans for the way they had been treated historically. Trump’s response:

Well, I’ll certainly look into it. But you know, I’ve never been big on apologizing—you do know that, right? They complain: ‘Trump never apologizes.’ I’ll look into it. We’re going to do one more. I’ll look into it. Okay let’s go we’re gonna do one more. Come on. We want a good one. Give me a fun one. Give me a fun question. Okay?

Trump and the charisma paradox

Why did Trump, a man who controls crowds of 20,000 with Prospero-like ease, stumble in the smaller, more intimate town hall setting? For one thing, Trump is used to “leading the orchestra,” says Smith, and not responding to specific questions posed by others.

This rare glimpse of Trump’s awkwardness hints that his celebrated charisma might have something to do with the large crowds he seems to prefer. And indeed, it’s much easier to be charming on a epic scale, says Queensland’s Haslam. Charisma emerges from the general spirit of a moment—the sense that the leader is “one of us”—and not from individual interactions with that leader, he explains.

A good deal of a person’s perceived charm depends on how fervently a person identifies with a certain group, says St. Andrew’s Reicher, and on the degree to which they feel the leader personifies that group. So if you feel defined by the notion “I am an American” and you believe Trump “symbolizes America,” you’re likely to find him wildly charismatic.

Trump’s weakness in town hall formats might delight his opponents. But none of the audience members I was friendly with—nor, for that matter, Keith Maupin—seemed bothered that Trump fumbled question after question. And that’s probably because the relationship between Trump and his Cincinnati supporters has already been forged.

Trump’s grand covenant

If people see enough of themselves in a leader, and that leader in themselves, a dearth of decorum, contempt for fact, a gelatinous command of policy—none of these will matter much to voters. A leader can float along on bombast as long as he speaks what feels true to the group.

The media is prone to marveling at the supposed mystery of how Trump flouts both the conventional wisdom of US elections and modern rules of public civility with such whimsical impunity—and how his supporters eat it up. But as Money-Kyrle’s analysis suggests, the “truth-telling” that Trump offers his supporters does indeed have historical precedent. And, sure, Trump’s knack for propagandist psychological games confirm the man’s genius for salesmanship. But its deeper insight comes from what it tells us about America.

The campaign trail mind games that whip the crowd into a mania of Trump fervor work because people, on some level, want them to. It’s fun. And the conversation Trump is giving voice to has been going on for a very long time, albeit in hushed tones and behind closed doors. Now, millions of Americans are hearing their own voices in his.

The conversation that takes place at Trump rallies is far more fundamental than anything encapsulated in a party platform. The urge that Trump is finally giving voice, authority and legitimacy to is redefining America’s vision of itself—to whom the country belongs, who deserves to live here, who is entitled to its economic bounty, and who must be punished for its perceived decay. And, ultimately, who gets to decide its destiny, and how.

Trump’s opponents might be offended by the very fact of this conversation. Or they might be baffled by why these topics—many of which have long been enshrined in America’s legal, political, and cultural institutions—might be up for debate at all. But they ignore Trump’s supporters at their peril.

What I learned in Ohio is that there is indeed a movement, as Trump so often tells the crowd—and he is just its messenger. His supporters are drawing moral authority not just from the canary-haired billionaire on the dais, but from each other, from the tens of thousands of kind, reasonable, likeminded people with whom they shared gum, backaches and the brief but ecstatic experience of becoming the single-mouthed crowd-creature at Trump rallies. Even if his presidential bid implodes, Trump may exit the race having converted the nascent resentment of a huge swath of voters into a coherent political organization. Maybe what should alarm his opponents isn’t simply that Trump might win the 2016 election—or even that he might win on a mandate to redraw the “who” and “what” of America. It’s that so many of its citizens want desperately to see him to try.

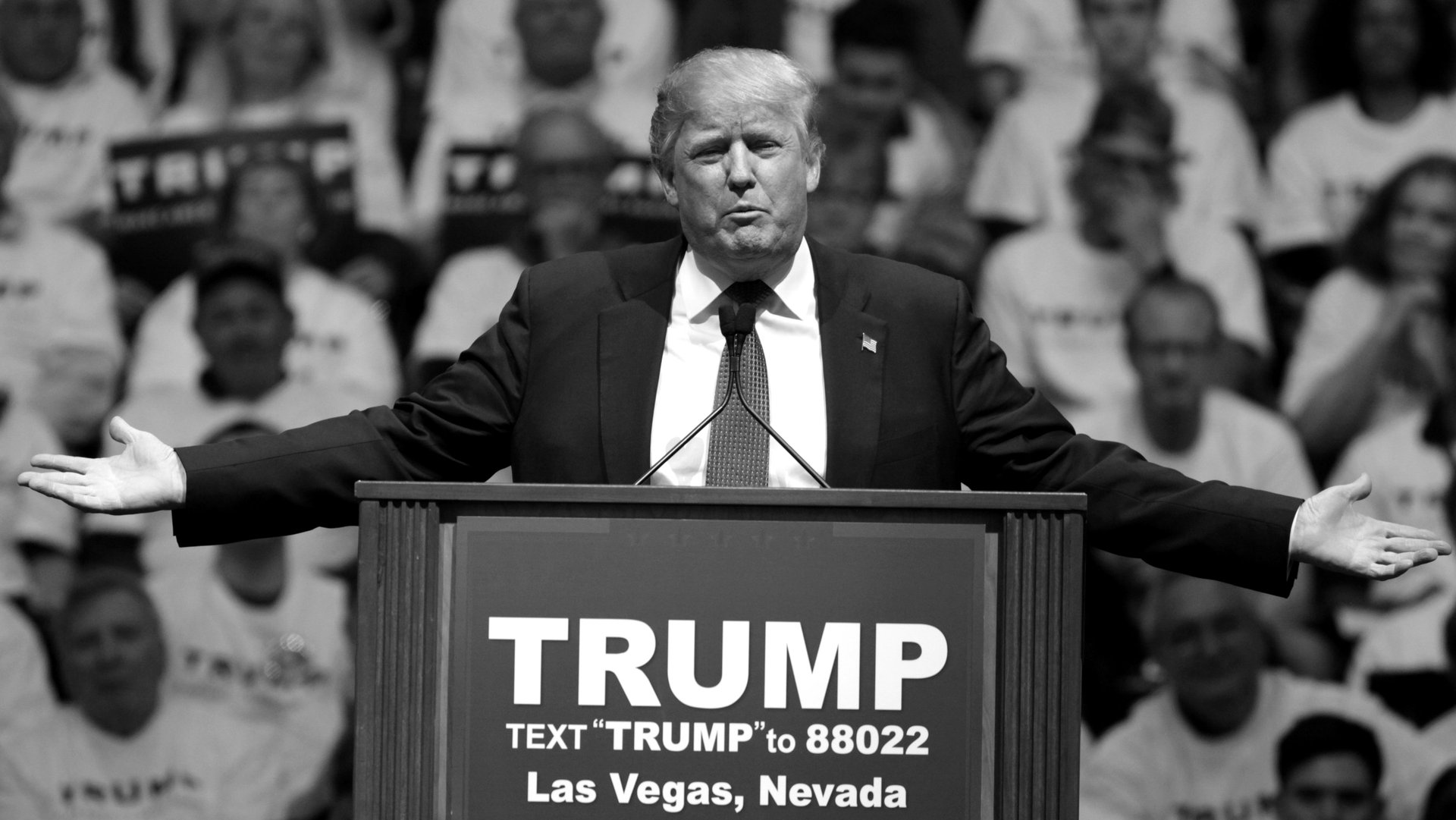

Headline image is by Gage Skidmore via Flickr (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; the image has been cropped and rendered in black and white). Image from Muscatine, Iowa, is by Evan Guest via Flickr (licensed under CC BY 2.0; image has been cropped). Images from Reno, Nevada, are by Darron Birgenheier/Flickr (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; Trump image has been cropped).