This theory explains why some siblings have absolutely nothing in common

For a long time, social scientists had a set way of thinking about how siblings influenced each other. Older children act as role models, advisors, and caretakers for younger ones. Older kids are more able to do things like read and ride bikes, or use manners and share first, paving the way for younger ones to watch and learn.

For a long time, social scientists had a set way of thinking about how siblings influenced each other. Older children act as role models, advisors, and caretakers for younger ones. Older kids are more able to do things like read and ride bikes, or use manners and share first, paving the way for younger ones to watch and learn.

Scientists call this social learning, observational learning, or modeling. Younger sis tries to be like older bro, and the result is siblings who behave in similar ways.

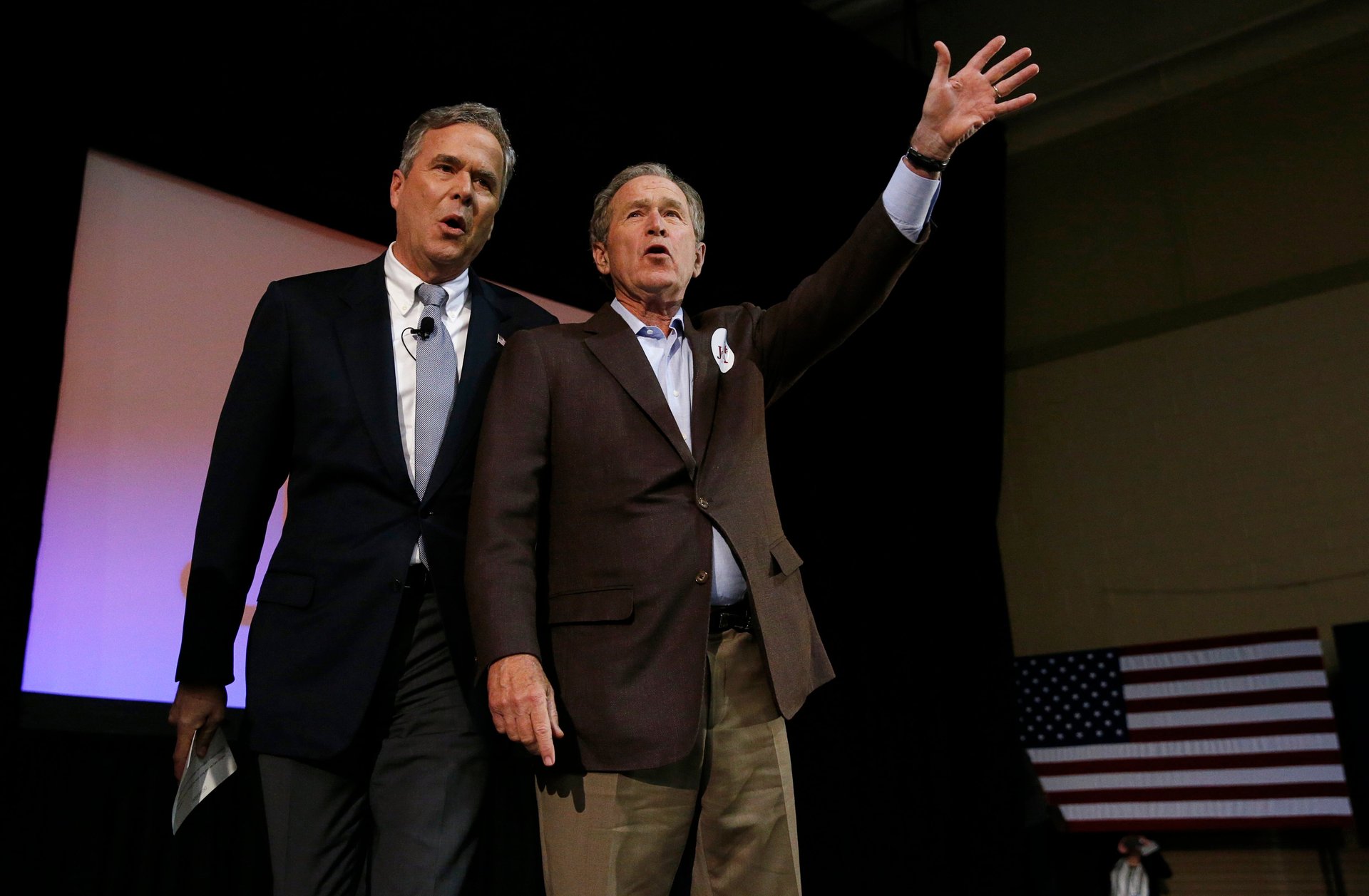

But what about the siblings who are radically different? One loves activities and outings, the other wants to stay home and play Lego; one is kind and courteous to everyone, the other refuses to even hug her grandmother?

There’s a theory for that too. It’s called deidentification.

The term was first used by Alfred Adler in the 1950s and it suggests that siblings consciously or unconsciously seek out different territory in order to reduce friction and improve their chances of getting some parental attention. “By being different we should mitigate competition and rivalry, which promotes more sibling harmony,” Shawn Whiteman, a professor at Purdue University, said.

Thus, if the eldest loves sports, the youngest ends up embracing music; if the oldest is gregarious, the next one is shy. And so on.

Whiteman and his colleagues set out to figure out which theory might be more prevalent, and whether they could uncover what drives siblings to pick one route over the other.

In a 2007 study of 171 adolescent sibling pairs, researchers found about 50% of siblings fell into the “modeling” group—that is, the younger one tried to be like his or her older sibling. Around 25% differentiated themselves (the deidentifiers), with the little one working hard to be nothing like the older one. The remaining 25% fell into the “we just live together” category—ie, there was no discernible pattern when it came to preferences in athletics, academics, art, or behavior.

Many factors beyond genetics influence how siblings develop. They have a shared environment—the same home, probably the same school—but within that context, they are treated differently by their parents, they have different friends, and experience different things.

Weirdly, Whiteman’s study concluded that siblings who deidentified did not necessarily get along better than those who were more similar. This contradicts the underlying premise of the theory—that by being different you promote harmony because you are competing less.

“When we find differentiation, the youth in that category tend to have less harmonious relationships rather than more,” Whiteman said. During adolescence, these siblings fight more and experience less intimacy.

Adolescence itself could be the problem—by early adulthood, when warring siblings have escaped the oppressive rules of their parents, they might find more common ground, he said.

All of this research is moving toward a few ends: trying to understand how to promote better sibling relationships, which can lead to greater happiness, and how to prevent bad behavior, which all parents would support wholeheartedly.