Uber is distracting us from a much bigger issue for the US economy

The Uber economy is tiny in size, but great in hype. While Uber drivers and other so-called gig workers are estimated to make up just 0.5% of the US labor force, big conversations are happening at every level of government over whether we should reshape labor policies to accommodate this new type of on-demand work.

The Uber economy is tiny in size, but great in hype. While Uber drivers and other so-called gig workers are estimated to make up just 0.5% of the US labor force, big conversations are happening at every level of government over whether we should reshape labor policies to accommodate this new type of on-demand work.

The constant whirl of news around Uber and its hotly funded Silicon Valley peers make these conversations feel topical, even urgent. But they may be distracting us from a much more important—if less glamorous—shift in the economy: the rapid growth of Americans in ”alternative work arrangements.”

Economists refer to ”alternative work arrangements” as a catch-all for non-standard jobs. The category includes temporary workers, on-call workers, workers provided by contract firms, and independent contractors or freelancers. What tends to unite these jobs is most often also what they lack: health insurance, the minimum wage—any of the benefits and employment protections typically built into workplaces.

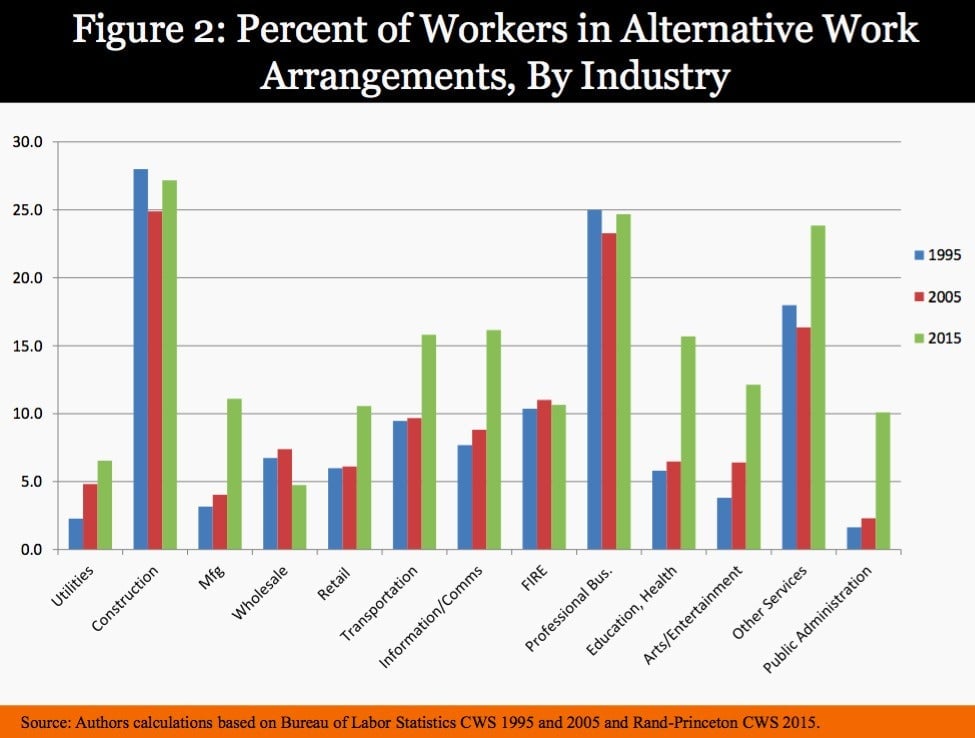

According to new research from prominent labor economists Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger, the share of Americans working these atypical jobs has increased from 10.1% a decade ago to 15.8% as of late last year. And nearly 40% of people in these jobs have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

“A striking conclusion of these estimates,” Katz and Krueger write, “is that all of the net employment growth in the US economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements.”

Think about that for a moment. Katz and Krueger are saying that over the last 10 years, all of our net gains in employment have come in jobs that aren’t what we traditionally think of as jobs. These aren’t the climb-your-way-to-the-top positions on which the American dream was imagined (a dream that is much harder to come by today). They’re temporary roles, contracted gigs, stuff that’s fundamentally transient.

A related employment term, contingent work, has been defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as “any job in which an individual does not have an explicit or implicit contract for long-term employment.” The BLS first tried to track these non-standard jobs in the 1990s, as many companies began trading standard employees for temporary, replaceable workers. “Has the era of lifetime jobs in the United States vanished and, in its stead, a ‘just-in-time’ age of ‘disposable’ workers appeared?” one BLS economist wondered in a 1996 paper.

Over the next decade, the bureau measured contingent and alternative work four times, but then its funding dried up. Other economists have since struggled to assess the “disposable worker” question. As one 2014 research paper noted, “it has been hard to find evidence of a strong, unambiguous shift toward nonstandard or contingent forms of work.”

Katz and Krueger’s research is important because it does offer that evidence. Alternative work is growing—and it’s much, much bigger than Uber. For every driver we talk about, there are even more educators, health care providers, janitors, public administrators, and construction workers who are seeing their jobs contracted out.

As gig economy companies are fond of saying, alternative work offers independence and flexibility.

But there are also real concerns. For starters, people in alternative jobs tend to earn less. Last year, independent contractors reported weekly earnings that were 28% lower than those of standard workers, even though their hourly wages were 17% higher. Contracted-out workers made similar hourly rates to standard workers, but earned 26% less per week.

Growth in alternative arrangements could drag down worker pay and treatment more broadly. And changes to labor policies being considered for a small subset of companies such as Uber could also have implications for much bigger US employers, such as Walmart.

Katz and Krueger acknowledge all of this. The labor market “is evolving in ways not fully captured in official statistics,” they note in a research presentation. “Does contracting out and increasing use of independent contractors threaten labor standards and contribute to rising wage inequality?”

Their paper doesn’t have the answers. But by putting some numbers to what looks like a major shift in our economy, it should draw attention to the conversation—and help move it beyond Uber.