How Cyprus would fail

Things are getting dicey for Cyprus. On March 16, the Mediterranean nation rejected a proposed €10 billion ($12.9 billion) bailout from the European Union, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF because it would have imposed a tax on depositors in the country’s banks, violating an important taboo. It rejected attempts to modify the terms of that bank levy. The ECB stood its ground, and now the country needs to come up with €5.8 billion to win that money from the troika (ECB, IMF, and EU). The Cypriot government is trying to do that, with late-night attempts to restructure banks and pass capital controls (paywall), but and it needs to find a plan that works—or else.

Things are getting dicey for Cyprus. On March 16, the Mediterranean nation rejected a proposed €10 billion ($12.9 billion) bailout from the European Union, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF because it would have imposed a tax on depositors in the country’s banks, violating an important taboo. It rejected attempts to modify the terms of that bank levy. The ECB stood its ground, and now the country needs to come up with €5.8 billion to win that money from the troika (ECB, IMF, and EU). The Cypriot government is trying to do that, with late-night attempts to restructure banks and pass capital controls (paywall), but and it needs to find a plan that works—or else.

Okay, but what does “or else” really mean? Here’s a look at what could happen:

Goodbye, ECB

The tiny Mediterranean tax haven is currently staying afloat based on special loans provided by the Central Bank of Cyprus, loans that are part of the Emergency Liquidity Assistance program (ELA). The ELA is a measure that’s sanctioned by the ECB for temporary use in emergency circumstances, and has been utilized multiple times throughout the euro crisis. The ECB prevents banks with poor-quality capital from borrowing funds from its normal pool. But illiquid banks—those that can’t get money because trading partners are afraid to lend to them—still need to fund their clients’ withdrawals. Therefore, in extraordinary circumstances, the ECB’s governing council allows national central banks to provide those loans instead to prevent a country’s financial system from failing.

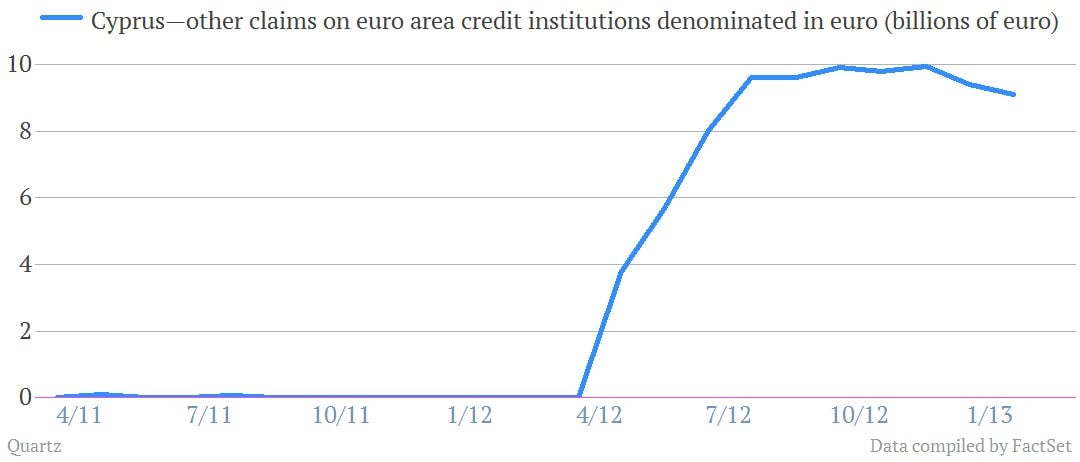

Cypriot banks have been hooked up to this ELA IV drip since last year. Our friends at FT Alphaville have discovered that data on ELA borrowing goes by the code name “other claims on euro area credit institutions denominated in euro” in central bank balance sheet documents. As the chart below shows, that borrowing picked up in July as the country was forced to recapitalize its two largest banks: Bank of Cyprus and Popular Bank (Laiki). The chart shows use of the ELA through January 2013, when the latest data were published.

Today, the ECB said it will discontinue the ELA funding to Cyprus after Monday, March 25, unless the country can come up with a plan to keep its banks solvent. So if we get to Monday and there’s not a plan, and the ECB will no longer allow Cyprus’s central bank to essentially print money to keep the banks alive. That doesn’t mean it will pull the €9.1 billion it has authorized Cyprus’s central bank to lend banks. That money is on the national central bank’s balance sheet, and so it will turn into a national liability.

Bank failure

The problem is that, when banks open Tuesday, March 26, they’ll be inundated with customer demands to withdraw cash. Without funding assistance from the ECB, banks won’t have the money available to provide cash for those withdrawals. Officials have already begun to enforce capital controls on deposits. Today, Cyprus Popular Bank (Laiki) limited ATM withdrawals to €260 per customer per day. The Cypriot government is vetting proposals that would “restrict noncash transactions, freeze check cashing, limit withdrawals and even convert checking accounts into fixed-term deposits,” according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

But because Cypriot banks are so heavily funded by deposits (and not loans from other banks), they’re still likely to fail without an outside capital injection. At that point, the Cypriot government is on the hook to depositors, and liable for insuring the first €100,000 in every account. “If the banks collapse the Cyprus government will be responsible for the deposit insurance: €30 billion. It sounds like a lot of money, but it’s even more so because the Cyprus GDP is only €18 billion,” warns Marc Chandler, the global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman.

Exit inevitable

Thus the worst case scenario—a failure of the Cypriot financial sector without management from the troika—probably results in Cyprus defaulting on its debt and exiting the euro. In order to stave off a massive complete collapse of the domestic economy and the evacuation and destruction of the capital that exists there, Cyprus would need the ability to print money and make good on the deposit insurance it’s promised. Without the support of the ECB, the Cypriot government would theoretically like to step in and backstop the banks, but it doesn’t have the funds on hand and is unable to access the financial markets.

The best way to do that is really by moving to a new currency. That situation would allow the Central Bank of Cyprus to print as much money as it needs to fund its bank backstop, and allow it to pump new money into a failing economy. Clearly, this would engender a massive devaluation. But in the medium-term at least it would allow Cyprus to return to competitiveness by making its labor, exports, and tourism less expensive relative to other countries. That would also help the government wipe its slate of government debt clean, at least theoretically.

Cyprus’s sovereign debt, however, could pose a nasty problem in this worst-case scenario. Morgan Stanley estimates that 60% of Cyprus’s government borrowing—or about €9 billion, based on Q3 2012 figures (pdf)—is denominated in bonds governed by UK law. It’s far more difficult to coerce owners of international-law bonds to change their tune, because another nation’s court dictates what can and cannot be changed. (Most Greek debt was denominated in Greek law, making it easier to restructure.) This means it will be more difficult for the Cypriot government to negotiate with its creditors and force them to accept new terms. This smacks of the legal problems Argentina is still having with US-denominated bonds, more than a decade after it defaulted on them.

Alternatives

But Cyprus’s exit from the euro would pose a deeper risk. ”People are going to think how are they going to fix Spain or Italy if they can’t fix this one?” Dieggo Ferro of Greylock Capital Management told Bloomberg TV. By taking a hard line on the €5.8 billion in funding needed and letting Cyprus go without help, the troika would fuel any skeptics who believed that it’s not up to the task of rescuing an economy in trouble.

Chandler believes that it would immediately ramp up pressure on Greece. Beyond Greece’s strong ties to Cyprus, he says, “markets are already anticipating pressure on them, and Greece is already as we know very vulnerable. In fact, the EU is postponing another tranche of aid to them.” These concerns could cause bank runs to spread through other troubled countries: Portugal, Spain, Italy, and even Ireland.

That’s why analysts resoundingly believe that the troika will be able to reach an agreement with Cyprus to extend the necessary funds, even if it means fudging the numbers. Morgan Stanley’s European Economics team reasons that the most likely worst-case scenario is still some kind of troika-led debt restructuring, that would allow Cyprus to extend maturities of its existing bonds:

Cypriot banks are likely to have a material outflow of deposits, causing a possible abrupt stalling of economic activity. This could challenge debt sustainability on the growth side, and investors may start pricing in an increasing probability of some sort of debt relief in addition to liability management.

This isn’t a great outcome for Cyprus, but it would at least alleviate pressure on Europe. “Our view is that things are not going to spiral out of control,” says Ferro. “That’s not necessarily about making Cyprus do well. Cyprus has big problems.”