Cyprus is a pawn in Russia’s power play against the EU

Before I went to Moscow as a correspondent a decade ago, a colleague recommended a book, Negotiating with the Soviets, by Raymond Smith. It outlines the Russian negotiating strategy: Act furious, establish a position of power, make outrageous demands, and then bargain down from there.

Before I went to Moscow as a correspondent a decade ago, a colleague recommended a book, Negotiating with the Soviets, by Raymond Smith. It outlines the Russian negotiating strategy: Act furious, establish a position of power, make outrageous demands, and then bargain down from there.

Russia has acted furious that the “troika” of international lenders failed to consult it on the Cyprus bailout plan, which would have involved imposing a levy on bank deposits in Cyprus, a large chunk of which are held by Russians.

It has established its position of power: Now that Cyprus has rejected the troika’s bailout plan and the troika looks like it’s rejecting Cyprus’s alternative proposal, Russia could single-handedly save the beleaguered island from default—and the euro zone from the body blow of a country leaving the single currency—by agreeing to restructure a €2.5 billion ($3.2 billion) loan to Cyprus. But it has refused.

So what will the outrageous demands be?

It might seem strange that Russia doesn’t just step in and help out. €2.5 billion is a piddling amount for Russia’s government. It’s far less than Russian depositors are thought to have stashed in Cypriot banks ($31 billion). It’s less than what those depositors would lose if the banks went under. It might even be less than what they would lose if the bank levy plan were adopted, especially if it were in a revised form that places a higher burden on richer depositors. On top of that, deferring the loan would earn Russia the Cypriots’ (not to mention Europe’s) undying gratitude. And it would probably enable Russia to squeeze a really sweet deal out of Cyprus for a cut of the gas reserves (albeit of uncertain size) the island recently discovered.

But for Moscow, this isn’t about Cyprus’s stability, its bank deposits, or its gas. It’s about Europe as a whole.

Relations between Russia and the EU have been growing steadily more tense. On the one hand, Europe doesn’t like being overly dependent on Russia for natural gas, and has been seeking other sources. On the other, it keeps criticizing Russia’s ever-worsening corruption and human rights record. And while Russians used to look yearningly to Europe, with its prosperity and freedoms, as a model, the crisis-hit euro zone now looks to them increasingly like a joke.

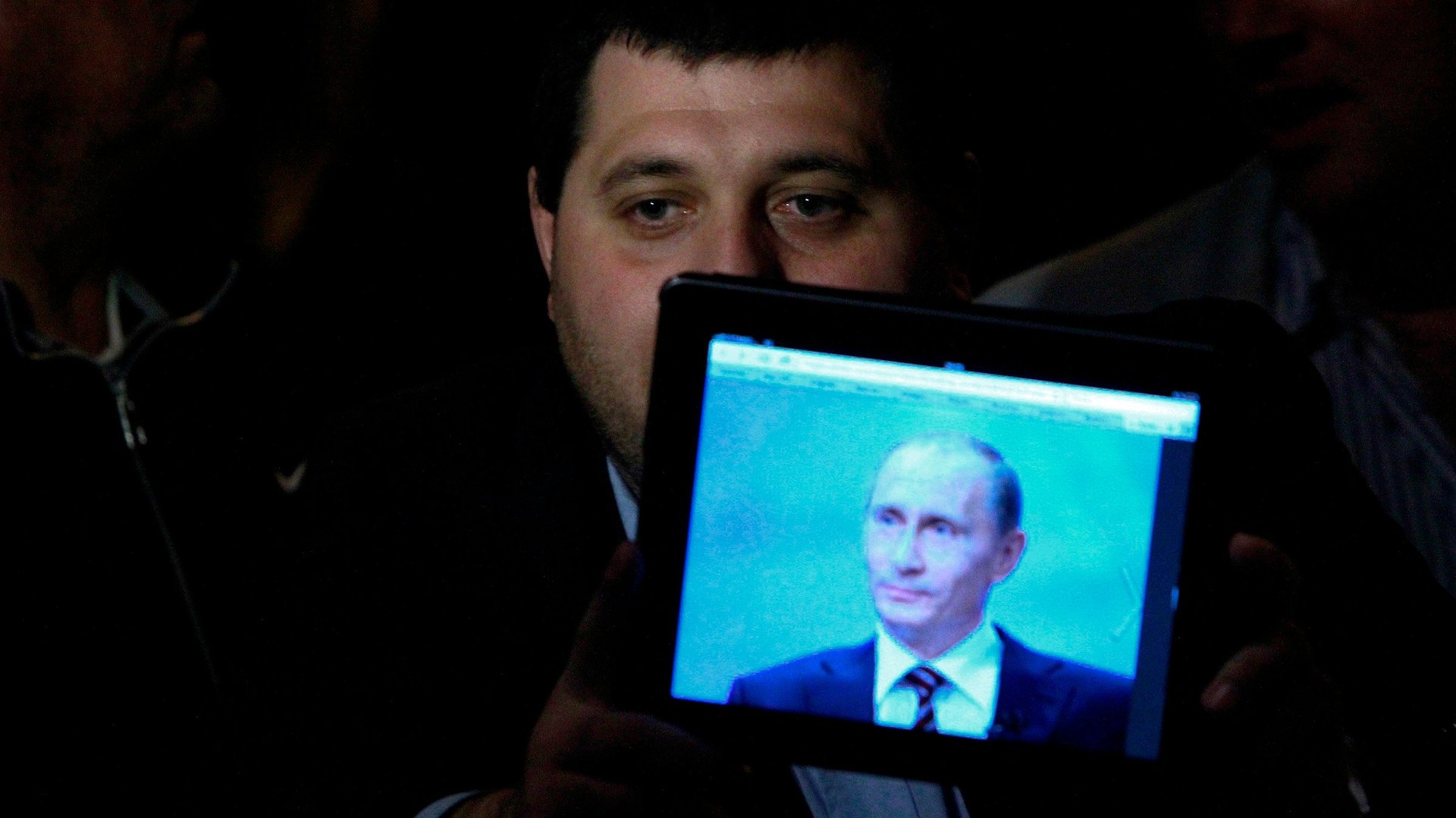

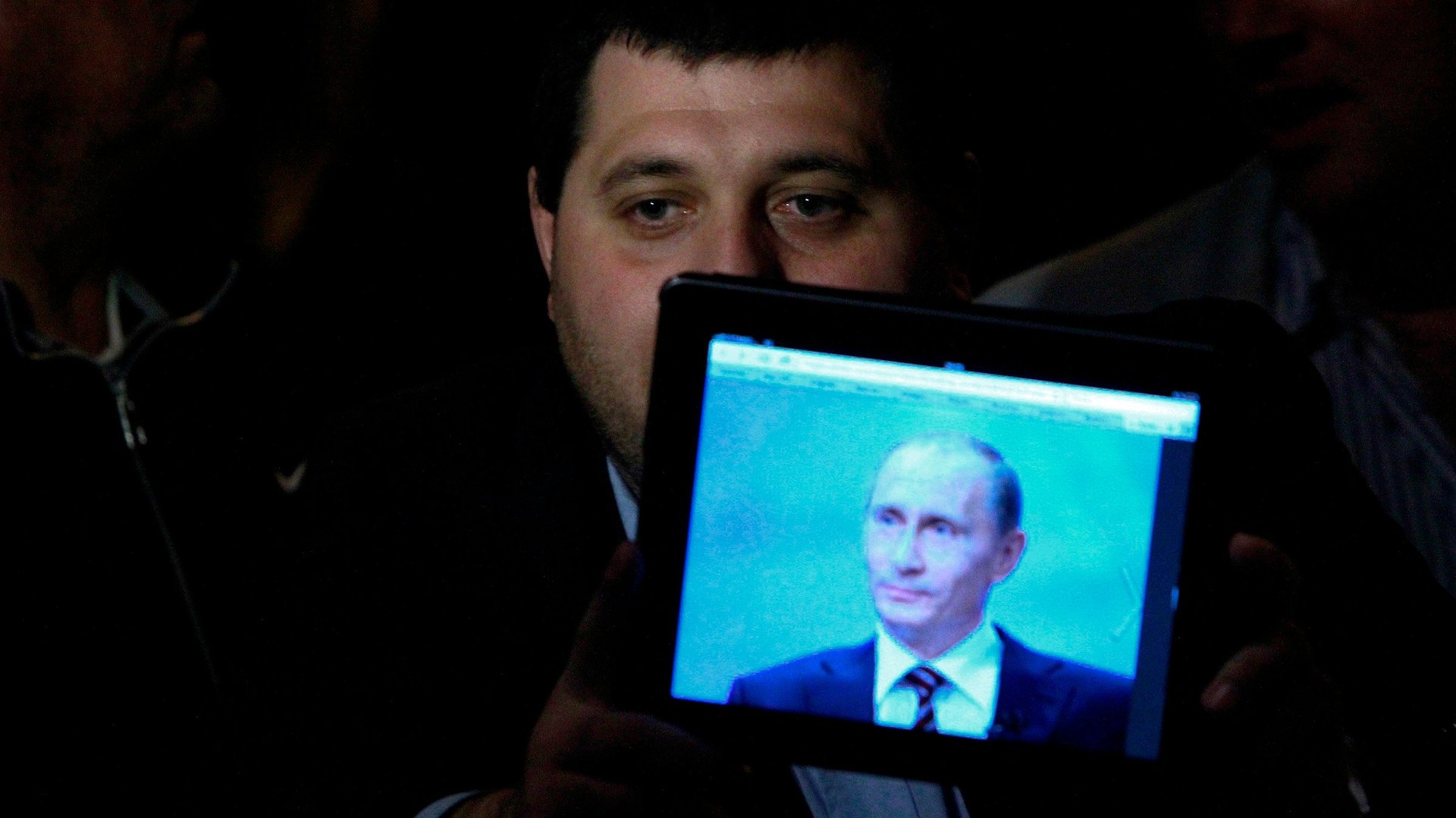

So the chaos over Cyprus is, in the words of a Russian economist interviewed by the FT (paywall), “a huge, huge gift to Putin”. The prospect of a #CypriOut, raising the specter of other exits and the possible collapse of the euro altogether, must have the Russian president rubbing his hands with delight. Anything that weakens Europe this much is worth far more to him than a few billion dollars of private Russian deposits or a tiny little Mediterranean gas field.

So if Russia decides to make a gambit, it will wait until the last possible moment, when Europe’s desperation is greatest. Perhaps it will seek a concession from the EU on something unrelated to Cyprus.

Or perhaps it will judge that nothing it can wrangle out of Europe outweighs the geopolitical capital—not to say the Schadenfreude—of just sitting back and watching European leaders running around like headless chickens, trying frantically to stave off what they fear will be the euro zone’s collapse.