Silicon Valley’s guru was everything Silicon Valley isn’t

Bill Campbell, the legendary coach to some of Silicon Valley’s most famous CEOs, had little in common with the leaders he mentored. That may be why he was able to earn their trust.

Bill Campbell, the legendary coach to some of Silicon Valley’s most famous CEOs, had little in common with the leaders he mentored. That may be why he was able to earn their trust.

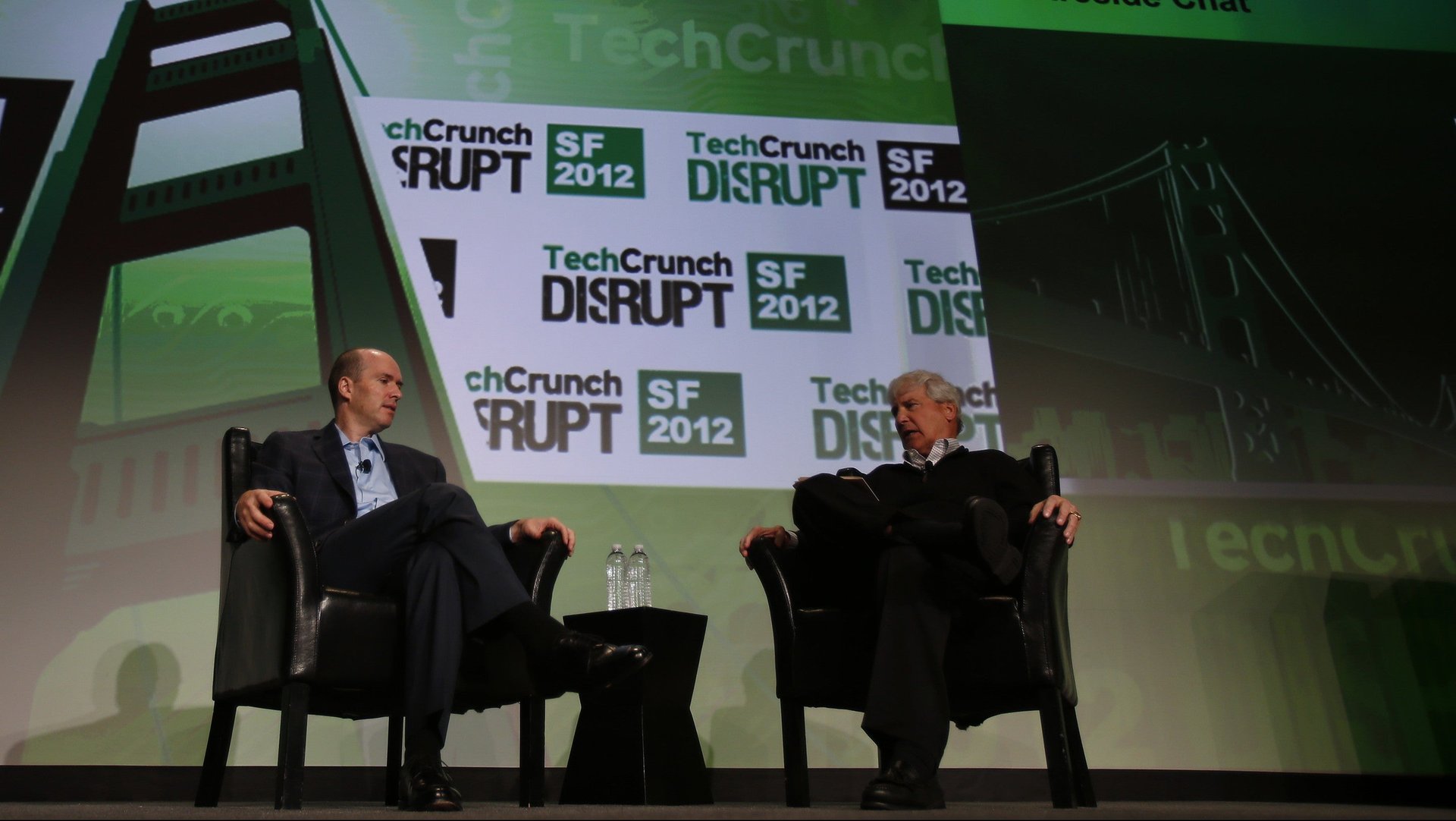

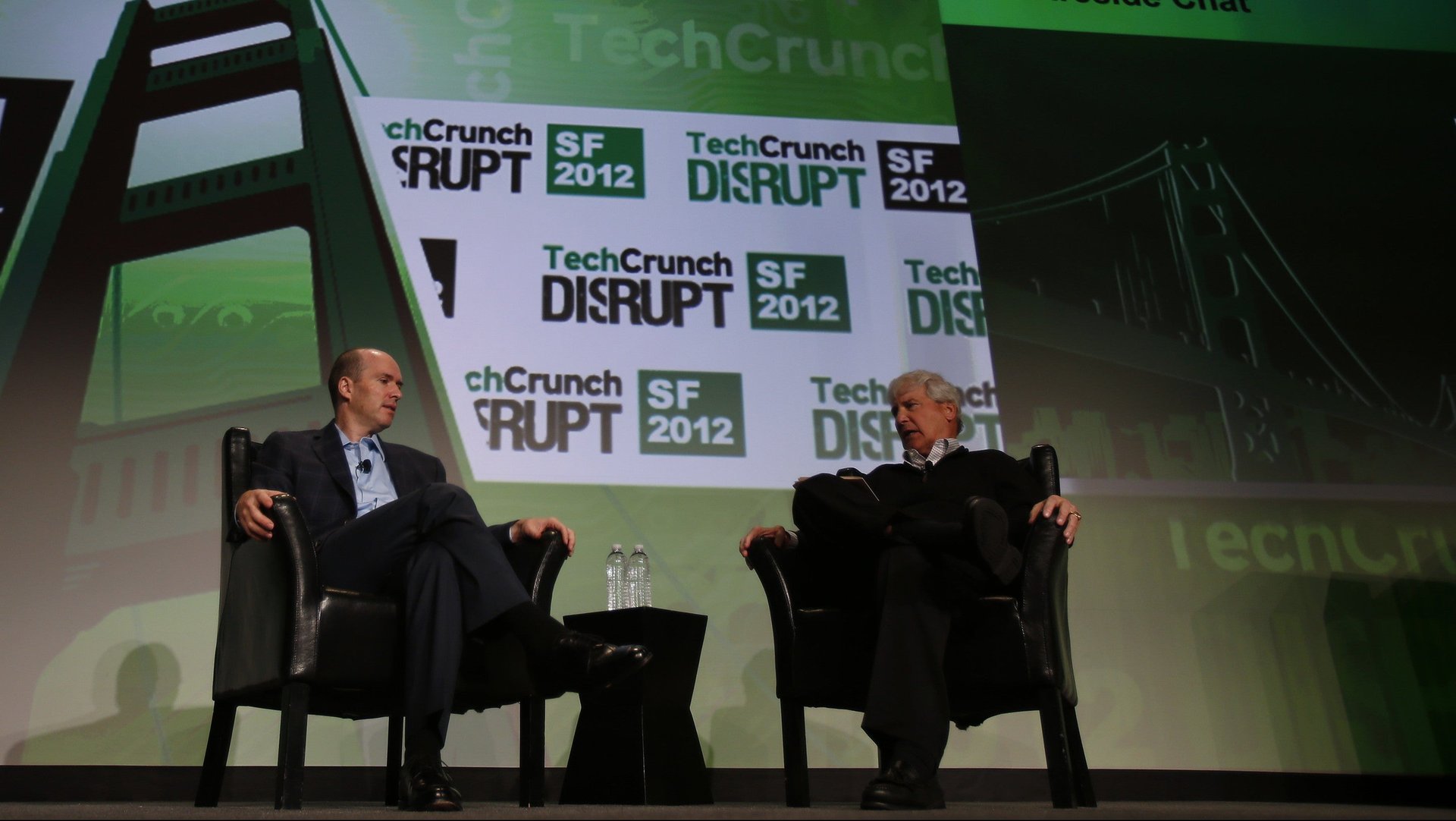

Campbell, who was 75 when he died of cancer on April 18, counseled Eric Schmidt at Google, Steve Jobs at Apple, and Jeff Bezos at Amazon, along with venture capitalists at high-profile firms like Kleiner Perkins and Andreessen Horowitz.

CEOs sought him out in part because he didn’t seek them out; executive coaching wasn’t Campbell’s business and he didn’t do it for money—in fact, he often refused pay, or would ask that companies donate instead to his charitable foundation. (A life-long Democrat, he accepted stock options from a company run by Marc Andreessen only after Andreessen threatened to donate them to the Republican party, according to Fortune.)

Unlike the executives he counseled, Campbell wasn’t an engineer or a tech visionary and he didn’t set out to change the world. His early ambitions were more modest: After playing football at Columbia University, he earned a master’s in education and became the team’s coach. He won just 12 of his 54 games as head coach, one of the worst records in the 146-year history of that dismal program and a questionable performance even by the standards of Silicon Valley, which has a reputation for tolerating failure.

After coaching, Campbell ended up working for Kodak, a company eventually destroyed by technology. It’s hard to imagine worse preparation for Silicon Valley.

But eventually Campbell drifted into a job at Apple—he was friends with the brother-in-law of then-CEO John Sculley—and found success as a motivator of the company’s salesforce. He later became a fixture on Apple’s board. His track record as a manager was still mixed when he was named CEO of Intuit, the software company, in 1994, where he doubled sales in four years at the helm.

Although Campbell had credibility as a Silicon Valley executive, the leaders he mentored didn’t ask him for help crunching numbers. His advice was more elemental, and at times, more essential. He understood human nature and guided his charges in their dealings with employees and board members. In salty language, often dispensed at a bar—he owned the Old Pro, a Palo Alto sports bar—Campbell reminded executives that leadership is more than deals and investment rounds.

He helped Schmidt run Google’s staff and board meetings, and listened as Jobs bounced off ideas during walks in their neighborhood. He advised all the leaders he counseled that attitude and behavior counts, and they shouldn’t be afraid to fire someone who exhibited poor character.

With his rough-hewn style and distinctly analog background, Campbell was a throwback, a big, friendly voice from an earlier age in the relentlessly forward-looking world of technology. It’s possible others could have offered the same advice to those CEOs—much of what he said wasn’t revolutionary—but because they trusted Campbell, they listened.