On a pedestrian bridge in Guangzhou, on a summer evening in 2009, I came upon Wu Yong Fu—a man in his early thirties who worked on the bridge. Cradled in his left hand was a simple digital camera; his right hand held a placard made up of various photographic portraits laminated in plastic. As people walked by, he would sidle up and cajole them to have their picture taken. Wu emanated a kind of wistful charm that served him well for attracting customers.

This was not my first time on the bridge. In 2005, while photographing in Guangzhou, I came upon an area known as Xiaobeilu (Little North Road). Its crumbling old structures abutted modern glassy towers, while its narrow alleys bordered a vast, elevated highway system. The pedestrian bridge allowed safe passage over the arterial road that ran through the area. Wanting the highest perspective possible, I walked up the stairs onto the bridge. An immediate sense of openness, light and expanse could be felt.

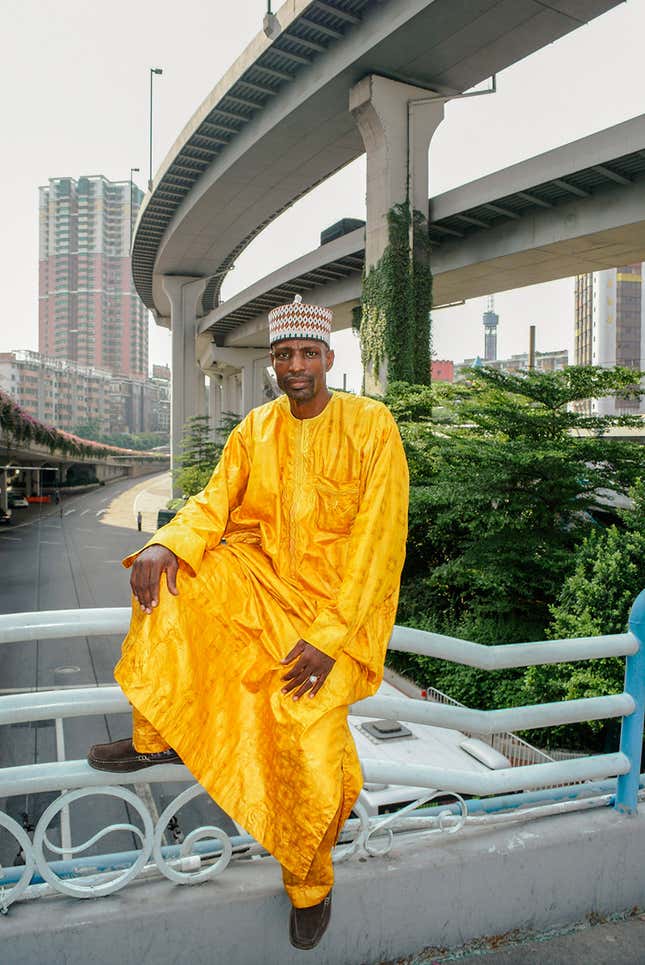

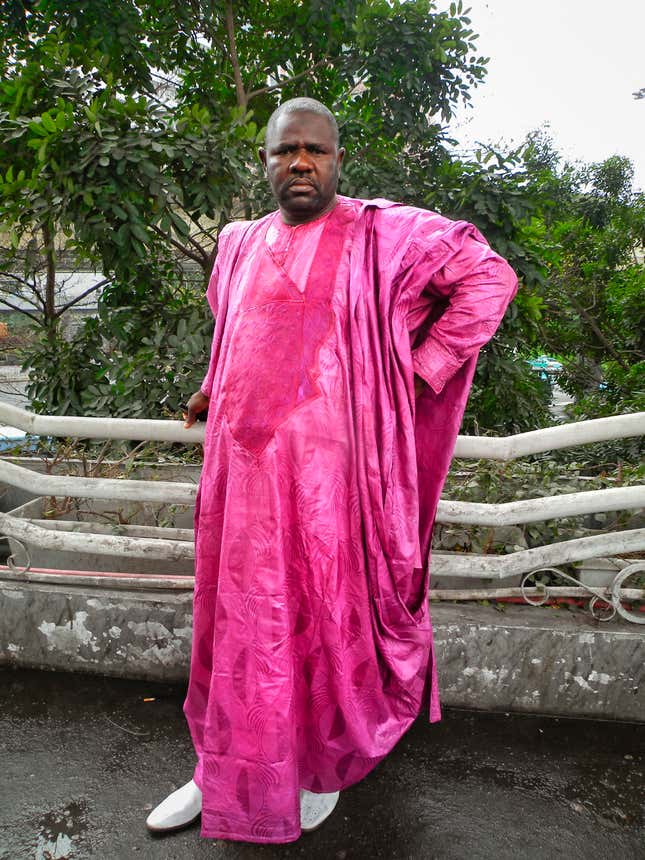

There were also many foreigners; those wearing dashikis and kaftans I guessed to be from Africa. I wondered if the Africans in Guangzhou were, in a sense, the flip side of China’s growing presence in Africa.

As someone who has long been involved with China, including a decade spent living and working there, and as someone who has worked in various parts of the African continent on multiple trips, something about the interaction of these two worlds captured my imagination. By the time I returned to Xiaobeilu in 2009, it had become known to the locals, irreverently, as “Chocolate City.”

While the number of Africans was considerable, there were also other foreigners—from the Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia—and Chinese migrants from the far corners of the country. For the most part, this cosmopolitan intersection of people was there to trade in the goods produced in the Pearl River Delta. However, it was the African presence that defined the area. The other groups had older ties and relationships to China based on proximity and trade routes. The African presence, at least on this scale and intensity, was something new.

Like the Africans and other groups in the area, I was also drawn to the pedestrian bridge. It not only functioned as a means of transportation linking two parts of the neighborhood together, but also as a town square of sorts. The bridge, suspended between the thoroughfare below and an elevated highway above, conveys a feeling of being lifted away from the dense urban fabric of the surroundings, and also, for a moment, from the cares and imperatives of everyday life.

The expressway above the bridge, lined with bougainvillea vines, offers shade from the midday sun. With the approach of sunset, people gather on the bridge to meet friends, smoke, gaze out at the city and lose themselves in thought. Chinese migrants transform the bridge into a night market as they unfurl plastic sheets and cover them with all manner of goods for sale: toys, underwear, cellphone cases, animal skins, ginseng. There’s even a man with a coiled snake offering its venom as a cure-all: a latter-day snake oil salesman.

Wu Yong Fu, originally from Jiangxi Province, is part of the vast migrant labor force that is a fundamental part of China’s economy and yet exists at the margins of the society. Together with his wife, he had been making a living for several years by producing portraits at tourist sites throughout the city. In addition to Chinese travelers, he was commissioned by Africans eager to have a memento of their time in China. While Wu photographed in other neighborhoods of Guangzhou he learned of the growing African population in the Xiaobeilu area and decided to begin working there exclusively. His business soon flourished.

Scrolling through the images on the back of his camera, I became increasingly fascinated with what I saw. The photographer, without intending to, had been documenting the stream of people from the various parts of Africa who had arrived in Guangzhou to trade and conduct other business. And, despite encountering a certain of degree of prejudice and discrimination, they often remained for extended stays.

While Wu’s images were mostly formal and direct, some were personal, unguarded and poignant. The gestures, clothing and sense of presence of Wu’s subjects reminded me of images by well-known African studio photographers, but instead of a studio back- drop, the architectural pastiche of contemporary downtown Guangzhou served as background. Sensing their significance, I asked Wu if he would share some of the images so that I could consider them further. He agreed, and transferred several hundred files to my computer before I returned to New York. Over the next few months, as I studied the photographs, I became more and more convinced that, in addition to their visual interest, they had broader cultural and historical value.

The following year, I went back to Guangzhou eager to see Wu’s recent work. To my surprise, he had been joined by a small group of photographers who were also shooting portraits on the bridge. Business had been going so well for Wu that his wife had invited her relatives from Hunan Province to take up the trade. Unfortunately, great tensions ensued among the bridge photographers as they fought over customers and prime location. Amid this strife, only one of the newcomers, Zeng Xian Fang, was willing to speak with me.

While Zeng enjoyed taking photographs, his primary motivation was to make a living and support his family. Unlike Wu, who seemed to have a real attachment to his images, Zeng deleted his at the end of each day. After conveying my sense of the importance of this work, Zeng began to view his pictures from a new perspective and saved them onto the hard drive I offered him.

Over the next several years, I returned to Guangzhou frequently, both to make my own images and to collect the photographs that Wu and Zeng had produced in the intervening periods. In 2011, Wu had a particularly bitter fight with one of the other photographers, a relative of his wife’s. This dispute, in addition to causing the end of his marriage, drove Wu to stop making photographs on the bridge.

Now, six years after meeting Wu and Zeng, I have come to see this project as a collaboration between these two photographers and myself, which documents a kind of metaphorical gateway for populations entering into China from Africa and the Global South: a sort of “Little North Road” into China.

It had been my assumption that this flow of people was an inevitable part of China’s future, a reverse current of China’s recent engagement abroad. This, however, no longer seems certain. As of this writing, the commerce on the bridge has been shut down by the Chinese authorities. Zeng, like Wu, has stopped making portraits on the bridge. The African population in Guangzhou, for political and economic reasons, is also declining. The thousands of images made by these two photographers are among what may come to represent the remaining documents of a moment that has already passed.

This is an excerpt from Little North Road: Africa in China, a book of photos by Traub, Wu and Zeng, published by Kehrer Verlag.