The second largest part of Apple’s revenue now comes from something called Services

Apple’s big surprise in its quarterly numbers isn’t the end of 13 years of go-go growth but the emergence of Services as a very large revenue category. This leads us to a cultural/structural question.

Apple’s big surprise in its quarterly numbers isn’t the end of 13 years of go-go growth but the emergence of Services as a very large revenue category. This leads us to a cultural/structural question.

A little fun with Wall Street’s ways before we take a more serious look at Apple’s recently released figures.

Consider two sets of numbers:

- Revenue: between $50 billion and $53 billion.

- Gross margin: between 39% and 39.5%.

- Operating expenses: between $6 billion and $6.1 billion.

- Other income/(expense): $325 million.

- Tax rate: 25.5%.

And:

- Revenue: $50.6 billion.

- Gross margin: 39.4%.

- Operating expenses: $5.9 billion.

- Other income/(expense): $155 million.

- Tax rate: 25.6%.

The first set is the first quarter guidance that Apple issued in January. (Guidance is financial argot, a sort of non-committal forecast.) The second set, from Apr. 26, is the company’s actual numbers for that quarter.

Comparing the two sets, what would a lay person say?

Bullseye!

The company landed right on the target it painted three months earlier. This has become standard practice: Like clockwork, Apple issues not-too-hot, not-too-cold quarterly guidance and faithfully meets it thirteen weeks later.

But when we look at the media headlines, we see this:

Really?

Wall Street anal-ists get paid, mirabile dictu, to second-guess company numbers. To have something to sell, the soothsayers can’t just parrot company guidance, they have to come up with better numbers. On TV shows and in blogs these performers quote “supply-chain sources” and channel checks—they split hairs and make Ouija Board utterances in an effort to explain why their own quarterly estimates should be used as a basis for short-term speculation.

Do the mountebanks repent when the actual numbers come out? Of course not—they double down: We didn’t miss Apple’s numbers. Apple missed ours. These are the rules; they’re well-established and will never change…we just have to remember how the show is scripted.

Turning to more serious matters, something really new just happened: After 13 years of uninterrupted growth, Apple’s numbers declined compared to the same quarter a year ago:

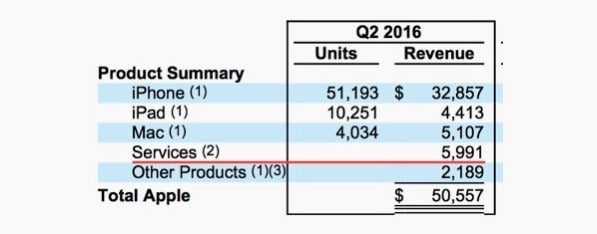

- Revenue: $50.6 billion (–13%).

- Net profit: $10.5 billion (– 22.5%).

- iPhone: 51.2 million units (–16%).

- iPad: 10.3 million units (– 19%).

- Mac: 4 million units (–12%).

- Services: $5.99 billion (+ 20%) ⬅︎.

With one exception—Services—everything went down.

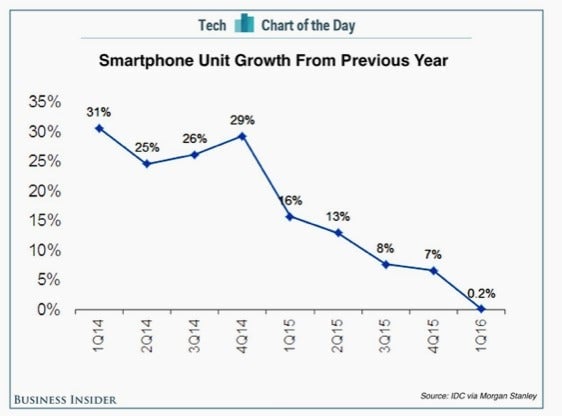

The Mac number isn’t surprising. The PC market has been on a downslope for more than two years, and the research firms Gartner and IDC have confirmed this continued decline for the first three months of 2016. What’s new is the decline in the smartphone market. A decade after the smartphone era began with Blackberry, Palm, and Nokia, IDC says “it’s gone flat”:

This raises a number of questions for Apple. For example, will less expensive smartphones “disrupt” the iPhone? Or, just as netbooks counterintuitively failed to kill the Max, will the company continue to build on its customer experience and prosper with aspirational, “affordable luxury” products?

We’ll take a closer look at the iPhone, iPad, and Mac results in a future Monday Note—there’s more than meets the eye in their latest numbers.

Today, we’ll turn to the Services number Apple just disclosed: $5.99 billion for the Jan. to Mar. 2016 quarter:

That’s 11.8% of total revenue, higher than Mac and iPad, second only to the iPhone. In contrast to the other declining lines, Services revenue is up 20% from the same quarter a year ago. A bigger surprise, perhaps, it is also higher than Facebook’s latest quarterly revenue: $5.38 billion.

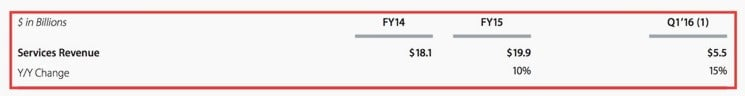

Just as with quarterly guidance, Apple management had “telegraphed” the event. In the Jan. 26 Earnings Call, “Services” were mentioned 31 times, and the company simultaneously published an unusual supplemental material document that highlighted the growing role and fast growth of its Services category:

Services grew 10% in 2015, 15% in the December quarter, and now 20% in the last three months. As maligned as Apple has been for its perceived poor performance in the Cloud, it must be doing something right in order to have gained such accelerating growth.

This leads to an inevitable question: Whither Services? Quoting Tim Cook in the Apr. 26 Earnings Call [as always, edits and emphasis mine]: “[…] we have developed a very large and profitable business in the Services area.”

As a result of this emphasis, many on Wall Street and elsewhere have started to ask if Apple is going to treat Services as a separate business with its own profit & loss statement. For Apple, this would be a momentous cultural shift away from its praised functional structure—one Tim Cook sees as fostering effective collaboration across groups such as operating system software, built-in apps, hardware, developer relations, and retail operations. The idea is for everyone to work together on the customer’s experience, as opposed to concentrating on an isolated goal: hardware revenue, App Store profits, or retail numbers.

The Company believes this functional management structure provides the following advantages:

A singular vision for the platform. In the past that vision came from Steve Jobs, the Company’s former Chief Executive Officer (‘CEO’), and continues under Tim Cook, the Company’s current CEO. The Company’s vision propagates down through the functions to the rest of the organization.

Seamless interoperability amongst the Company’s products.

Ideas and information shared across the organization.

People with brains and a good pen disagree: Ben Thompson, on his Stratechery blog suggests Apple can’t win the Services game with a functional organization:

[…] the key to Apple actually delivering on its services vision—is to start with the question of accountability and work backwards: Apple’s services need to be separated from the devices that are core to the company, and the managers of those services need to be held accountable via dollars and cents.

Others, such as John Kirk, hold a more nuanced view. Kirk quotes Amazon’s visionary leader as a caution against switching business models: “It’s very difficult for a publicly traded company to switch,” Bezos said. “So, if you’ve been holding a rock concert, and you want to hold a ballet, that transition is going to be difficult.”

I agree. A company’s culture is extremely hard to change once, like a concrete foundation, it has set. It may actually be impossible: I can’t think of a single mature company that has managed to change its culture.

I read Apple as a personal computing company. It wins or loses through the experience it delivers to its customers. Once upon a time, revenue came mostly from its personal computers, small, medium, and large. Software and Services had one and only one purpose: pushing up personal computers’ volumes and margins. Hardware, software, and Services coalesced into what we now call an ecosystem. Over time, as a result of the size of the installed base of Apple devices, Services became substantial, the number two revenue category—but, for reasons just discussed, it shouldn’t be run as a separate division.

That said, one shouldn’t dismiss the power of incentives. In a division organization, they’re clear to everyone involved. But they lead to destructive inter-division fights, as with the Microsoft of old:

In a functional arrangement, it takes strong, respected leadership to get individuals to sacrifice the immediate gratification of local numbers to the global, deferred success of a company-wide project.

There’s no way out of the dilemma. There is no way to get the sharp focus of divisional organizations and the cooperation and malleability of a functional structure. We can only hope that the toxic waste of success won’t let mediocrity and obesity set in.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.