This is what happens when your mother dies

“What do you want to list as your profession–housewife?”

“What do you want to list as your profession–housewife?”

The funeral director was talking to my 86-year-old mother. He was gathering information for her obituary to be placed in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Nine months earlier, my mother had been diagnosed with incurable colon cancer. It was March 2015, and after several rounds of chemotherapy, her oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic had given up. Clinical symptoms indicated her cancer had spread. She had, perhaps, months to live.

Housewife or homemaker is an inadequate description of my mother’s life. She had not had a career to “lean in” to, as Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg would put it. But neither had she spent her days cleaning, cooking and eating bonbons on the couch while watching soap operas during her leisure hours, as the titles seemed to suggest.

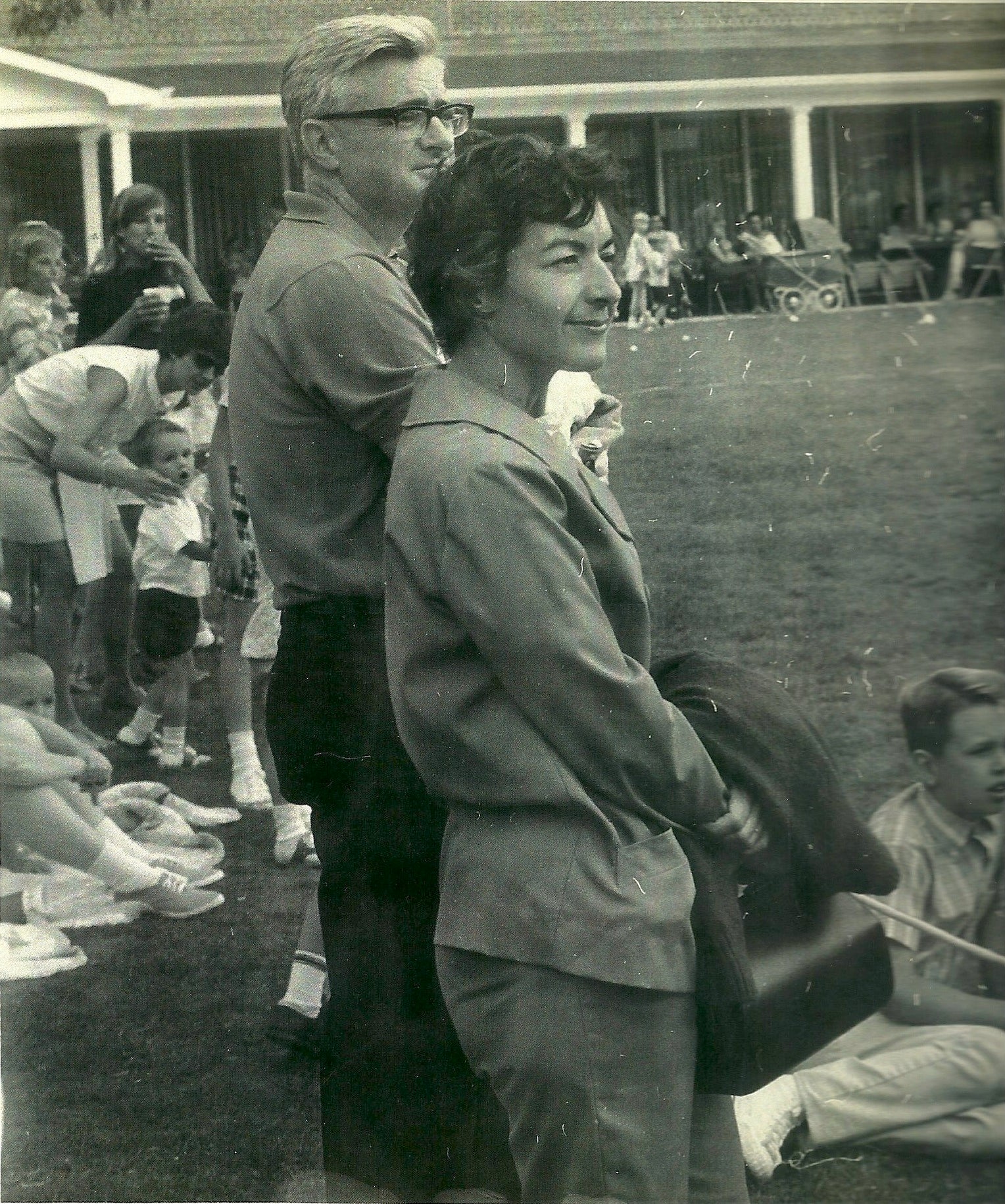

What she had done was stay married to my father for 65 happy years, raise three children and lead, as I discovered during the year of her illness, an intellectually adventurous life. What I realized was that her path was as exploratory as my own–which, as a reporter and editor for some of the nation’s biggest publications, has taken me all over the world and into the homes of some of the globe’s most influential men.

Women who came of age during the 1950s often are pigeonholed as either bored suburban housewives or striving singletons expected to sleep with the boss to get ahead. They were, a recent New York magazine article declared, victims of a government-backed industrial/advertising complex that convinced them their highest calling was “the maintenance of a domestic sanctuary for men on whom they would depend economically. In order to care for the home, these women would rely on new products, like vacuum cleaners and washing machines, sales of which would in turn line the pockets of the husbands who ran the companies that provided these goods.”

Nonsense. My mother’s life bore no resemblance to that. She was “not domestic,” as my father pointed out after her death, having never really learned how to keep house despite the fact that her mother cleaned houses for a living. She knew how to cook only two things when she married at age 21. “I was just grateful she did that,” my father told me. In the love letters exchanged between them during their engagement, my father details the process for making zinc sulfide, including all the chemical formulas, so she could understand his new job at General Electric. They were intellectual equals. I don’t think my father’s desire to have children–he was the one who pushed to start a family–was some sinister move to keep the economic wheels of GE turning.

Born in 1928, Norma Schaller grew up in Rochester, New York, the second child and only daughter of German immigrants who came to the U.S. after World War I. She was the smart one, the gifted athlete who, unlike her older brother, was adored by her domineering father. She played golf, ran track, was popular in high school, and met Eleanor Roosevelt while serving as the editor of her high school newspaper. Her grades earned her a scholarship at the University of Rochester where, long before Larry Summers put his foot in his mouth about the inability of the female sex to master numbers, she majored in math.

She thus had almost every advantage a career-minded woman graduating college in 1949 might have had, aside from being born into wealth and privilege. She had self-confidence, looks, STEM-smarts, first-generation ambition and, in high school at least, the traits of a natural leader. “She could have been a CEO,” said my father, who spent his career as a manager at GE in Cleveland.

This is what happened instead.

In fall of her senior year, in 1948, while attending her advanced math class, she met my father. She was one of two women in the class, though my father says, “as far as I was concerned, there was only one.” He was there by accident. Three years her senior, his education had been delayed by his Army service in World War II, which entailed, among other things, working at Los Alamos on the atom bomb. The math class was an elective on the way to getting his master’s in chemical engineering.

My mother was informally engaged to her high school sweetheart, but it wasn’t a love match on her part. “He never really listened to me,” she said. But she had immediate chemistry with my father, who came from a different part of town and a different background, although, like my mother, he was the first of his family to go to college.

A year later, they were engaged. They married in December 1949. My father lined up a job in GE’s chemical and metallurgical management training program. For the next five years, they moved from place to place. While GE’s training materials were written using only the word “man” and the pronoun “he,” my mother got jobs at the company each time he transferred. In 1952, five months pregnant with my brother, her boss asked her, “Isn’t about time you quit?” Three years later, they settled in Cleveland, built their own home and had two more children. By the time that last kid was in kindergarten, she was in her 30s, her work experience a distant memory.

Now what?

She became president of the local PTA, helped her kids with their homework, typed their term papers, taught them how to use the library, played golf, bridge, entertained friends and, yes, baked cookies. Then she had her obsessions. She would get interested in a topic, usually spurred by a book, a movie, or a political figure. She’d read every book, magazine and newspaper on the subject, piling up clippings that she’d eventually put into notebooks and also send to friends, her children, and people she thought might be interested, even if she didn’t actually know them.

After I left home, it was not unusual to get in the mail several envelopes a week of clips about topics she thought I might find interesting, or would help me with my own story research. After we bought her a computer and she discovered the internet, her research ballooned. When I cleaned out the house after her death, we found bound notebooks about Obama, the Clintons, Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Jane Austen, the Wild West, Africa. “She had a whole secret life,” my father said.

In the last several years, that secret life included an obsession with the famous Mitford sisters, only one of whom, Debo, the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, was still alive. The Mitfords were six sisters who traced their ancestry to the Norman Conquest and grew up in a series of great estates and country houses in England. One became one of Hitler’s girlfriends; another, a communist; another, Nancy, a well-known writer. Debo, the youngest, came to her title accidentally, by marrying the second son of the 10th Duke of Devonshire who inherited the title when his brother, who had married John F. Kennedy’s sister, died in World War II.

Somehow, in the course of her research and book reading, my mother began writing Debo, sending her relevant clippings from the New York Times or elsewhere that often chronicled the doings of the Kennedys. And she got replies. My suburban “housewife” mother was corresponding with an aristocratic Duchess in England.

When Debo died in 2014, a few months after my own mother’s cancer diagnosis, my mother was distraught. She had obtained a first-edition book from the Cleveland Public Library, where she had been on a trustees’ volunteer board, and she had planned to send it as a gift to Debo, partly as a joke, given that the Duchess was known for being not much of a reader. In the end we sent it to her son, the 12th Duke. He too wrote back.

In her 40s, my mother did go back to work. She got a job in the payroll department of the suburb we lived in, briefly became finance director, then worked in the budget department of Mount Sinai hospital in downtown Cleveland. She “retired” five years later, saying she planned to get a masters in computer science or math. But by then, my father’s parents were ill and she found herself commuting to Rochester every week. Loki the dog, too, took ill and had to be put down. My father decided to retire. By her mid-50s, she had no children at home, hadn’t started an academic program, had a healthy and compatible husband able to travel, and children living and working in Denver, California and, variously, New York and London. Grandchildren were likely on the way. Why not pay some visits?

Many women I’ve talked to hate Sandberg’s book, noting that her story, packed with mentors and good luck, bears little resemblance to their own. But the one true thing she wrote is this: “The single most important career decision that a woman makes is whether she will have a life partner and who that partner is.” Except that it’s the single most important life decision. And it’s also true for men. Without my mother, my father would have not have had the life he had. And without him, she wouldn’t have had hers. “She was the best thing that ever happened to me,” my father says. A generation later, my married brothers would say the same thing about their relationships.

I could argue that had my mother been born a generation later, she would have become a CEO and a hero to the Sheryl Sandbergs of the millennial generation. Then again, I didn’t become a CEO, either. Like everyone, she made choices as circumstances presented themselves. Most of hers were good ones. She had three children; one is a doctor, the other a journalist, another a chemical engineer. We all completed college, got jobs, didn’t do drugs or fall off some other proverbial cliff. “Dad and I are so proud of all of you,” she said. “You literally expanded our horizons.”

As a teenager, I had often accused my mother of not using the education she earned from her scholarship. She never really applied the math she’d studied, all those differential equations. She poured her talent into her family. And as many women who have worked to get to the top know, that was simpler than fighting for a job, or a career.

“I liked working,” my mother told me the last year of her life, when I queried her on its trajectory. “But there wasn’t anything that grabbed me so much that I wanted to do it. I read all these biographies of women, oftentimes black women. I wondered, how do they have so much gumption to go up against all of society and succeed?”

A month before she died, she started complaining of headaches. She was already under palliative care, but she had done so well, her vitals and blood counts so good that we hoped she could go back into chemotherapy treatment. It might give her months more of life. She had even been able to play nine holes of golf. It fell to me to tell her the results of the CT scan we had ordered to determine the cause of her headaches.

The cancer had spread. It had crossed the blood-brain barrier and riddled her brain with tumors. It was now a matter of time and not much of it. I started crying. I told her I loved her and was sorry I hadn’t married and given her grandchildren.

She asked me to help my father out with legal issues. Then she said, “I could have had the life you’ve had.

“But I wouldn’t have given up having you three kids.”