WhatsApp messages from one of the inmates leading Syria’s massive prison mutiny

Early on the morning of Sep. 27, 2013, three cars and more than a dozen fully armed men broke into Mohammed’s house and took him. For a full 24 hours, he says, he was hung from the ceiling in a room at a government military base. “I was beaten and tortured before being transferred to Hama Central Prison,” he says. “To this day, I have not received any sort of trial, and hundreds of prisoners are just like me. We just want justice.”

Early on the morning of Sep. 27, 2013, three cars and more than a dozen fully armed men broke into Mohammed’s house and took him. For a full 24 hours, he says, he was hung from the ceiling in a room at a government military base. “I was beaten and tortured before being transferred to Hama Central Prison,” he says. “To this day, I have not received any sort of trial, and hundreds of prisoners are just like me. We just want justice.”

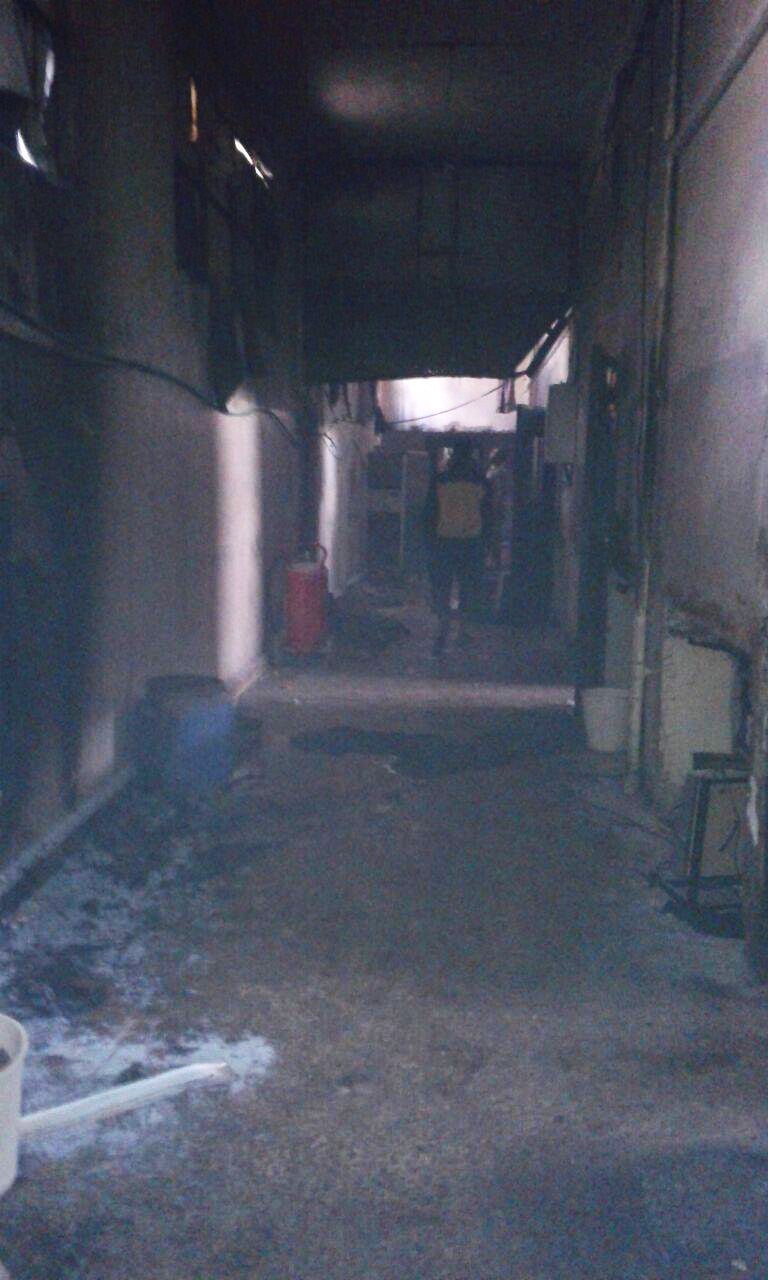

Mohammed is one of the 1,200 prisoners who took over Hama prison in Syria earlier this month. (We communicated with him via WhatsApp’s voice messaging.) After a brief siege by government forces, the inmates are waiting through a tense truce that is expected to hold through Saturday, May 14. The stakes are high: In the 1980s, over 1,000 inmates were killed by government troops at Tadmur prison in Palmyra, according to the Syrian Human Rights Committee.

Mohammed, 38, is from Hama, but has lived within the walls of the prison since Sep. 2013, charged with inciting terrorist activity. Terrorism is a common accusation made by the Assad government to justify detention of political dissidents. In 2012, one award-winning human-rights activist critical of the Assad regime was imprisoned for three years on charges of “publicizing terrorist acts.”

On May 1, 2016, Mohammed and his fellow prisoners organized an uprising against Hama guards. The revolt was precipitated by what Mohammed alleges was the mistreatment of a prisoner with cancer, who was chained en route to the hospital to receive chemotherapy, and not permitted to stay overnight for monitoring by doctors.

“We responded with a hunger strike, demanding better treatment for the man,” Mohammed says. “They transferred him to the hospital where he later died, on May 1, the first day of the riot.”

The prisoners’ uprising that day was also sparked by fears of an extrajudicial execution of fellow inmates. Violence erupted when Syrian police came to transfer eight Hama detainees to Sednaya military prison, where military police were accused of shooting up to 25 inmates in 2008.

“We broke the doors, we fought the guards, we didn’t let them take any of us,” says Mohammed. “And we were able to take nine guards as hostages.”

The nine guards were released on May 8. According to Mohammed they have since been “punished” by government officials for allowing the takeover to occur, and for letting inmates smuggle mobile phones into the prison in the first place. When Hama’s inmates later made contact with government officials to negotiate the standoff, they were asked to identify which guards had been bribed.

“It is easy to smuggle phones into the jail. We have a corrupt system,” Mohammed says. “It’s rare today to see a government official or a jail guard who is not corrupt, especially when their salaries are not enough to feed their families.” The mobile phone he has been using was brought into the jail by guards, who were bribed between $20 and $500 USD.

Now that the inmates have struck a truce with the government, water and electricity have been restored to the prison. Mohammed believes that he and his comrades have endured thanks to their cellphones, which allow them a voice to the outside world. “Our [voices] on social media and our ability to reach the outside world have only saved us time,” he says.

The inmates are currently demanding to be visited by the Red Cross or some other international humanitarian organization to alleviate deteriorating conditions and secure their survival, says Mohammed. “We have more than 140 prisoners with critical health conditions; they are in need of medicine and medical treatment.” The Red Cross has said it is aware of the standoff, telling Quartz, “We are not part of any negotiations, but remain ready to play our role of neutral intermediary if required and agreed to by the authorities.”

As well as allowing an aid organization on to the premises, the inmates are also demanding the release of 400 political prisoners currently held in the prison by the Assad regime. About 80 have reportedly been released thus far, as part of the truce.

Local rebel group Ajnad al-Sham released a statement last week in solidarity with the Hama prisoners, according to Al Jazeera, promising to attack government forces if the prisoners’ demands are not met.

As they wait for the government’s next move, Hama’s inmates worry about what will come once the truce is over. “The Syrian government has crossed every possible red line,” Mohammed says, referring to human-rights violations in the rest of Syria. “[They have] proved how little they care about violating detainees’ rights, especially after the leak of the Caesar photos.”

He refers to a defector, known as Caesar, who in 2014 leaked tens of thousands of images showing the bodies of detainees who died gruesome deaths in the country’s detention centers. “We are waiting and anticipating,” Mohammed says. “We know that if we fail here, we will be punished and massacred in the dark.”