Is there a better ketchup than Heinz? Without the shelf space, we’ll never find out

The first step to disrupting the supermarket condiments aisle is to show up on the shelves.

The first step to disrupting the supermarket condiments aisle is to show up on the shelves.

In most American grocery stores, options for mayonnaise and mustard are few. When it comes to ketchup, it’s even more scant. Shoppers typically have three choices: Kraft Heinz, Hunt’s and the store brand. It’s a tightly controlled market, but one small New York company aims to upset the decades-long condiment stasis.

And it may have a fighting chance.

In five years, Sir Kensington’s, the brainchild of a couple 2008 Brown University graduates, has carved out shelf space in boutique food shops, natural food grocery stores, about 200 Safeways and all Whole Foods Market locations. It will get its biggest opportunity in September, when the brand’s mayonnaise will be tested among shoppers in 10 Northern California Costco stores.

If Costco shoppers like it and the big warehouse store commits to ketchup, mustard and stocking the brand in up to 460 more locations, it will be a game changer for Sir Kensington’s. It will also show that Hunt’s and Kraft Heinz no longer dictate America’s condiment tastes.

“It’s definitely big,” said Jared Koerten, an analyst at Euromonitor. “Making that jump…into the mainstream aisle is the challenge. Costco can be a huge launching point for some of these brands.”

Sir Kensington’s may be minuscule compared to current industry behemoths, but its foray into the condiment aisle resembles other attacks suffered by giant food companies in recent years. US shoppers want healthier foods with ingredients they can recognize, and they don’t trust big food companies to deliver. Between 2009 and 2014, smaller US food companies captured $18 billion from the multinational giants, according to research by Boston Consulting Group.

In response, major companies have changed the recipes of their biggest products. They’ve also scooped up many of their upstart competitors. General Mills bought Annie’s Homegrown organic food company for $820 million; Hormel Foods acquired Justin’s nut butter brand; Coca-Cola bought Honest Tea; and Danone now owns Stonyfield Farm, to name a few.

Ketchups, mustards, dressings and mayo have enjoyed more stability than yogurt and tea, but companies such as Sir Kensington’s and Hampton Creek are trailblazing through the condiment market. Hidden Valley and Wishbone salad dressings have ceded market share to premium brands. And Kraft Heinz barbecue sauce has been clobbered over the last decade by Sweet Baby Ray’s, which overtook the giant brand in 2010 as the top selling barbecue flavoring.

“The long term horizon is just more threatening for some of these [big] companies,” Koerten said, adding that Sir Kensington’s growing sales already closely match the trajectories of other successful upstart brands.

Sir Kensington’s was created by Scott Norton and Mark Ramadan, who dreamed about making the perfect ketchup while sitting in college classes. After Brown, Ramadan joined a top US consulting firm and Norton moved to Tokyo to work in finance, but both were nagged by the idea of making a better ketchup.

“We had this idea that food in America was changing, and that ketchup and condiments were being left behind,” Norton said.

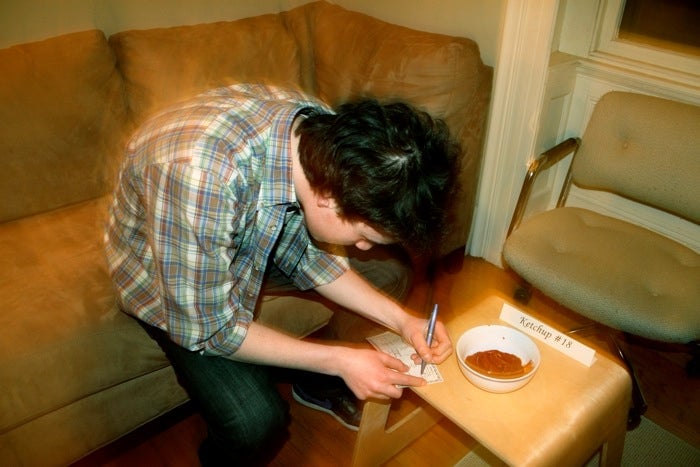

At school, they had thrown a series of ketchup-tasting parties for friends to try a hodgepodge of their tomato concoctions. The pair flirted with all sorts of ketchup styles, including a wacky “Christmas-flavored” ketchup and also one that incorporated Asian ingredients such as ginger and rice vinegar. They finally settled on two: classic and spicy. The Brown parties were dressy cocktail affairs, but those who attended recall them as a way to conduct low cost market research.

“The ketchups were laid out so that one could blind taste test them,” said Woody Schneider, who recalled attending several of the tastings. “Ketchup was seen as a hole in the marketplace that seemed like it could be filled.”

Nonetheless, disruption in condiments, particularly ketchup, is notoriously difficult. Del Monte attempted to squeeze onto the shelf alongside Kraft Heinz and Hunt’s a dozen years ago, but as detailed by Malcolm Gladwell in a 2004 New Yorker story, even it had trouble going up against the two top tomatoes:

Ketchup aficionados say that there’s a disquieting unevenness to the tomato notes in Del Monte ketchup: Tomatoes vary, in acidity and sweetness and the ratio of solids to liquid, according to the seed variety used, the time of year they are harvested, the soil in which they are grown, and the weather during the growing season. Unless all those variables are tightly controlled, one batch of ketchup can end up too watery and another can be too strong.

Sir Kensington’s founders were not deterred. After reconnecting in 2010, the duo produced their first manufactured batch. Since then, the firm has expanded into mustard, mayonnaise and vegan mayonnaise, giving it greater leverage with retailers.

“Just because nobody got the flavor balance right doesn’t mean it couldn’t be done,” Norton said.

Last year Sir Kensington’s raised $8.5 million from private equity group Verlinvest and a handful of individual investors. What started in a college apartment is now an eight-figure company headquartered at a New York City office in the trendy SoHo district, with production operations in Rochester, New York and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

Sir Kensington’s isn’t trying to replicate already-popular condiments so much as it’s trying to best them by using premium, higher-cost ingredients. Whereas Kraft Heinz uses tomato concentrate (including in its organic line) and high-fructose corn syrup to sweeten its ketchup, Sir Kensington’s lists “tomatoes” as its first ingredient and organic sugar as its sweetener. In mayonnaise, Sir Kensington’s uses free-range chicken eggs and sunflower oil; Hellmann’s brand contains at least 50% cage-free egg product and cheaper soybean oil.

Norton and Ramadan price their products between 50% and double the price of leading brands, but maintain theirs is a healthier condiment. To stand out as a premium brand, they package most of their products in glassware.

Making a better ketchup is one thing. Getting it on store shelves is another. Kraft Heinz, which did not return requests for comment, maintains a powerful grip on supermarket ketchup shelves. But Kraft, perhaps fearful of losing out in ketchup, has lately taken on other condiments. Most recently, it’s been distracted by a difficult yellow mustard war against French’s, the powerful, venerable brand owned by UK’s Reckitt Benckiser Group.

That, plus the generally low level of competition in ketchup, has allowed Sir Kensington’s to wedge its way onto shelves in select locations such as health stores and Whole Foods (which now accounts for 20% of the brand’s retail revenue). It’s also served at Bareburger’s 42 US locations; Gott’s Roadside, a small California chain; Sweetgreen; Epic Burger in Chicago; PJ Clarke’s in New York; and it’s the ketchup you’ll get if you order room service at The Wynn hotel in Las Vegas. In all, the brand is sold in 5,000 stores in the US, Norton said. That number will balloon further if Costco accepts the brand.

“Our goal is to be the leading natural condiment brand in America,” Norton said.

Asked if he thinks Kraft Heinz and Hunt’s are aware of his company, Norton didn’t skip a beat.

“If we’re not on their radars, then they are asleep at the switch,” he said.

The next several years may give way to volatility for ketchup, mustard and mayo, but that’s good news for hungry young brands looking to grab market share and give consumers more choice.

“We want to be a household name,” Norton said.