As Detroit enters a new chapter, an iconic photographer is recognized for capturing its past

Leni Sinclair is surrounded by memories of Detroit’s rebellious past.

Leni Sinclair is surrounded by memories of Detroit’s rebellious past.

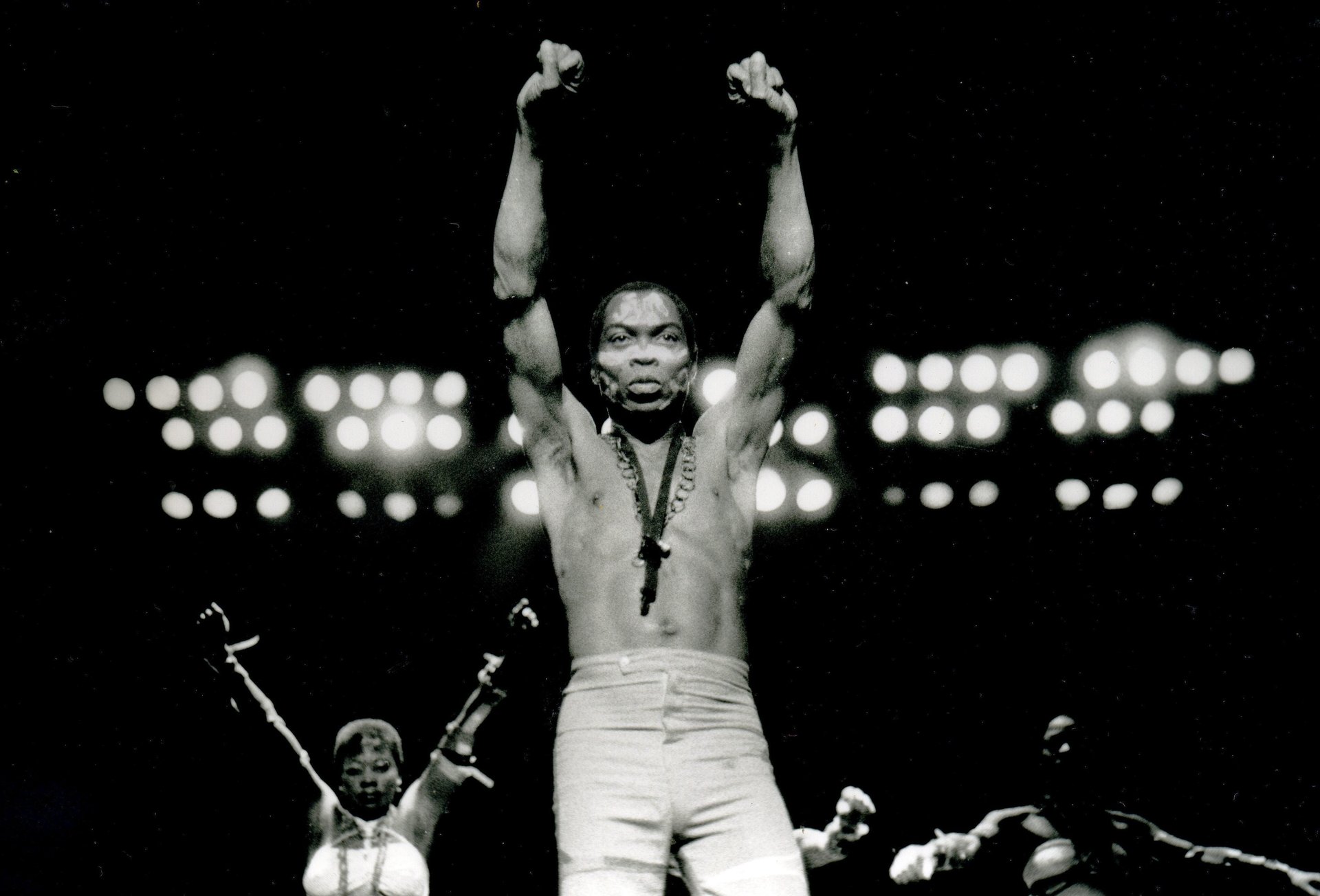

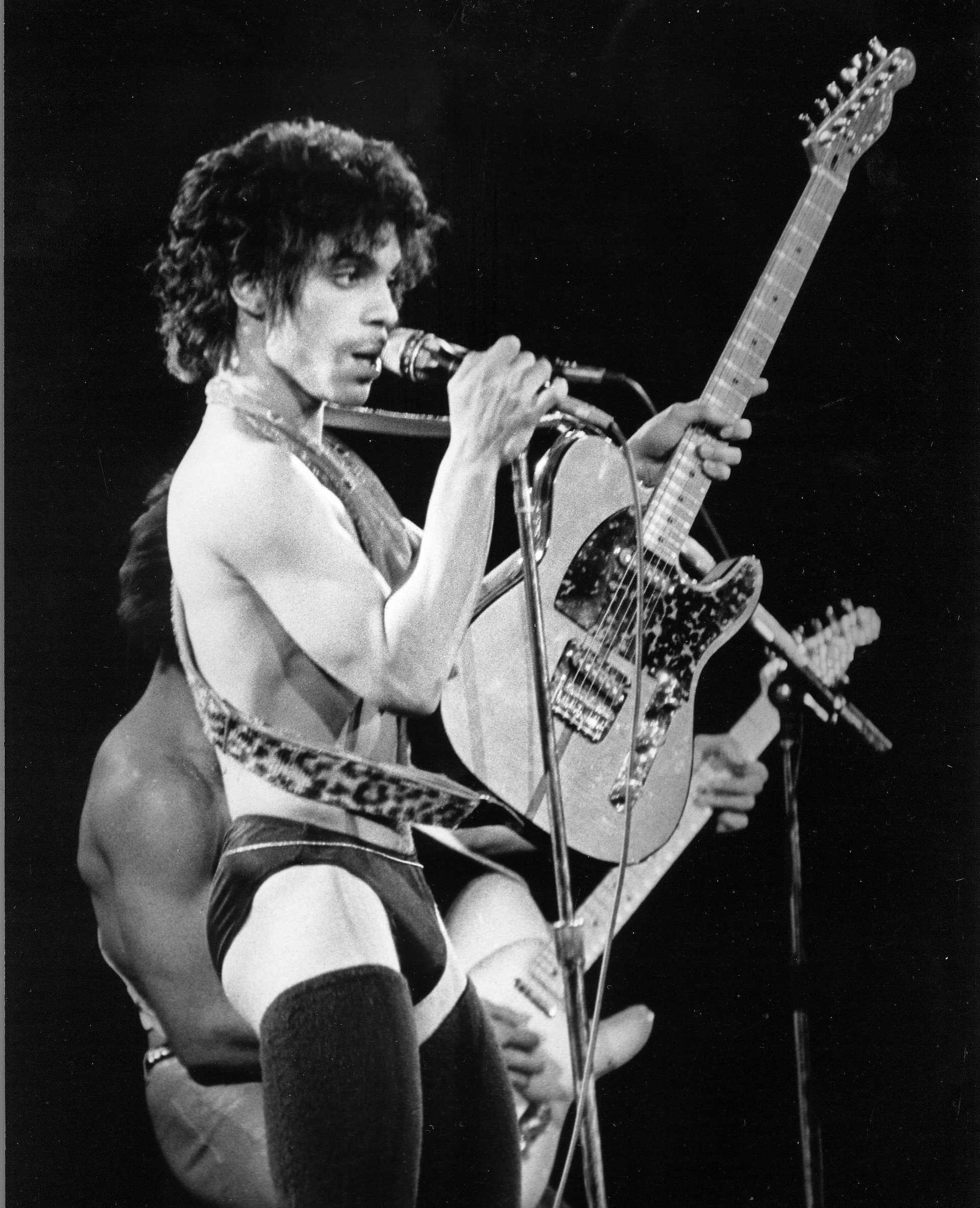

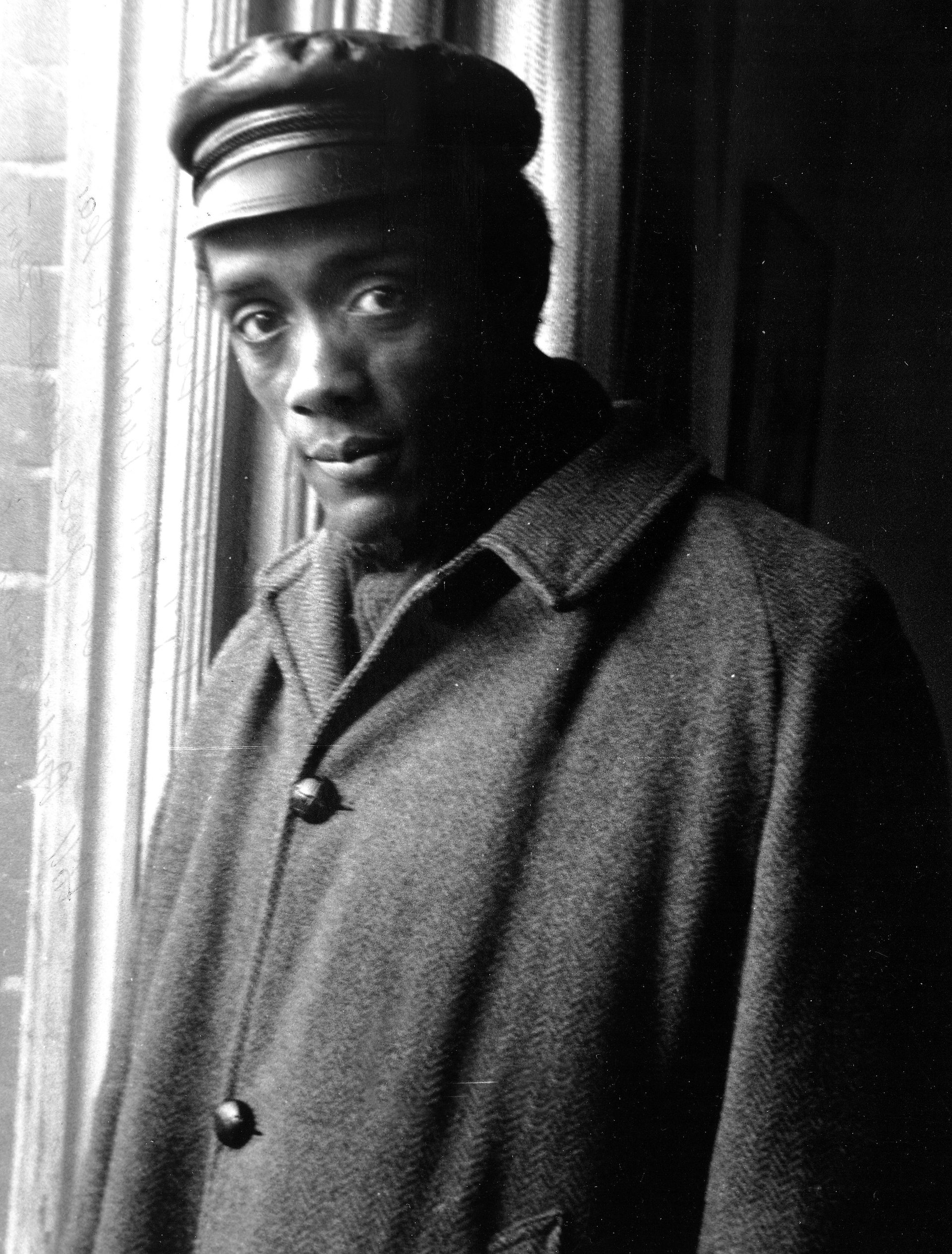

The 76-year-old photographer and Detroit activist’s small house, within walking distance of 8 Mile Road, is home to a rich archive of American counterculture. Boxes full of prints and negatives, memorabilia, piles of books, albums, and newspaper clippings line her walls. They are a tribute to Detroit’s role in generating the proto-punk of MC5 and Iggy Pop, nourishing jazz giants like Fela Kuti, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Sun Ra, and inspiring musical legends such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Prince.

This treasure trove has been here, within these walls, for decades, proof of Sinclair’s commitment to the city. “I own Detroit, and Detroit owns me,” Sinclair is fond of saying.

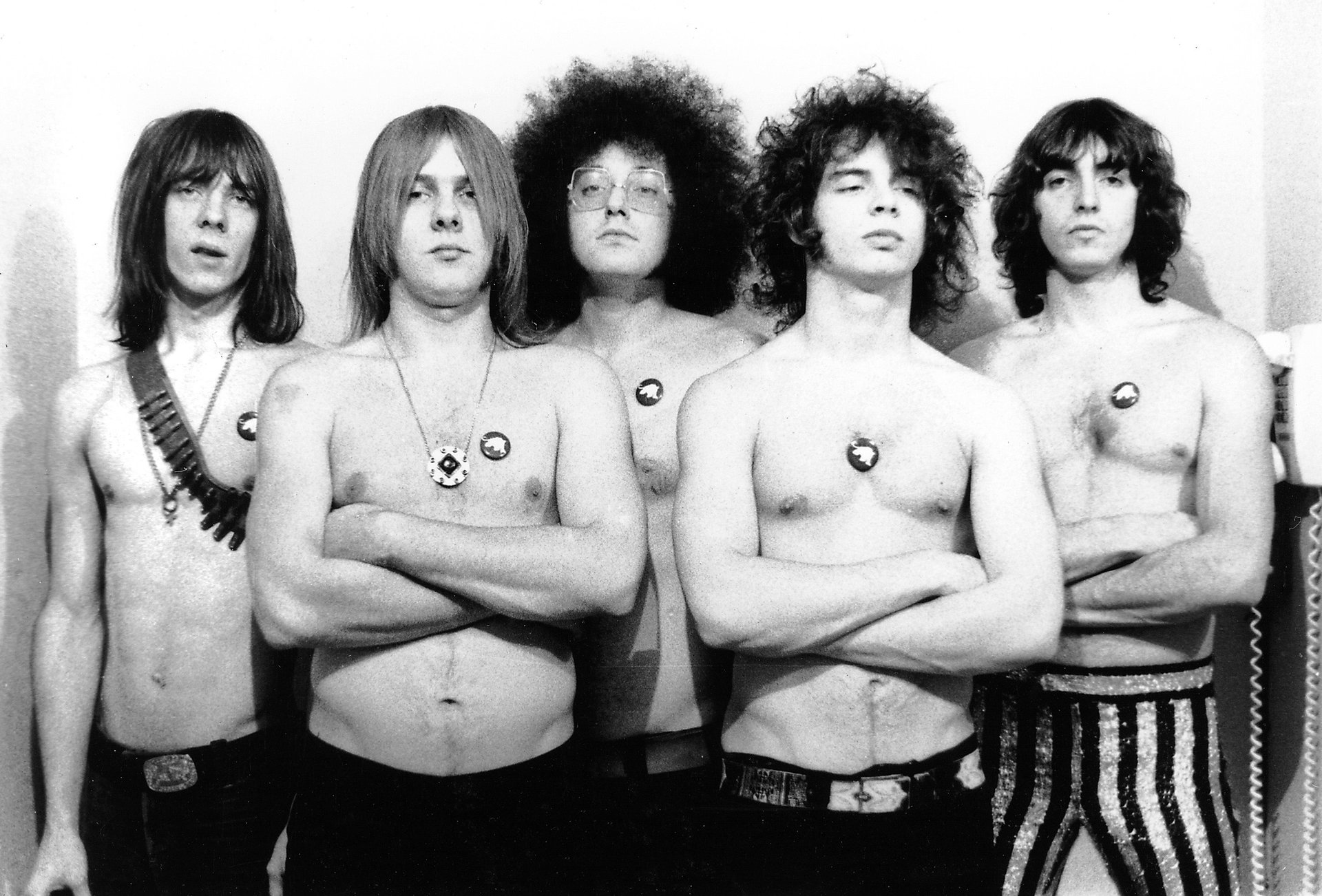

Sinclair is the keeper of this archive, and the creator of its most iconic images, and she’s been increasingly recognized for both roles in recent years. During the 1960s and 70s, she captured scenes of a young Iggy Pop hugging mike stands and MC5 posing with pins stuck in their chests (with tape, she says). Her career as a photographer is deeply intertwined with the turmoil of the city’s economic and cultural history.

Born Magdalene Arndt, Sinclair was 19 when she escaped to the US from Communist-era East Germany in 1959.When she first arrived, Detroit’s population was about 1.6 million, more than twice what it is today, and the racial tension that would eventually explode into fiery rage was already palpable. On June 23, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. led a march on Detroit streets and delivered a first version of his “I Have a Dream” speech. Sinclair was so impressed by his words that she found her way to King’s historic march in Washington, two months later.

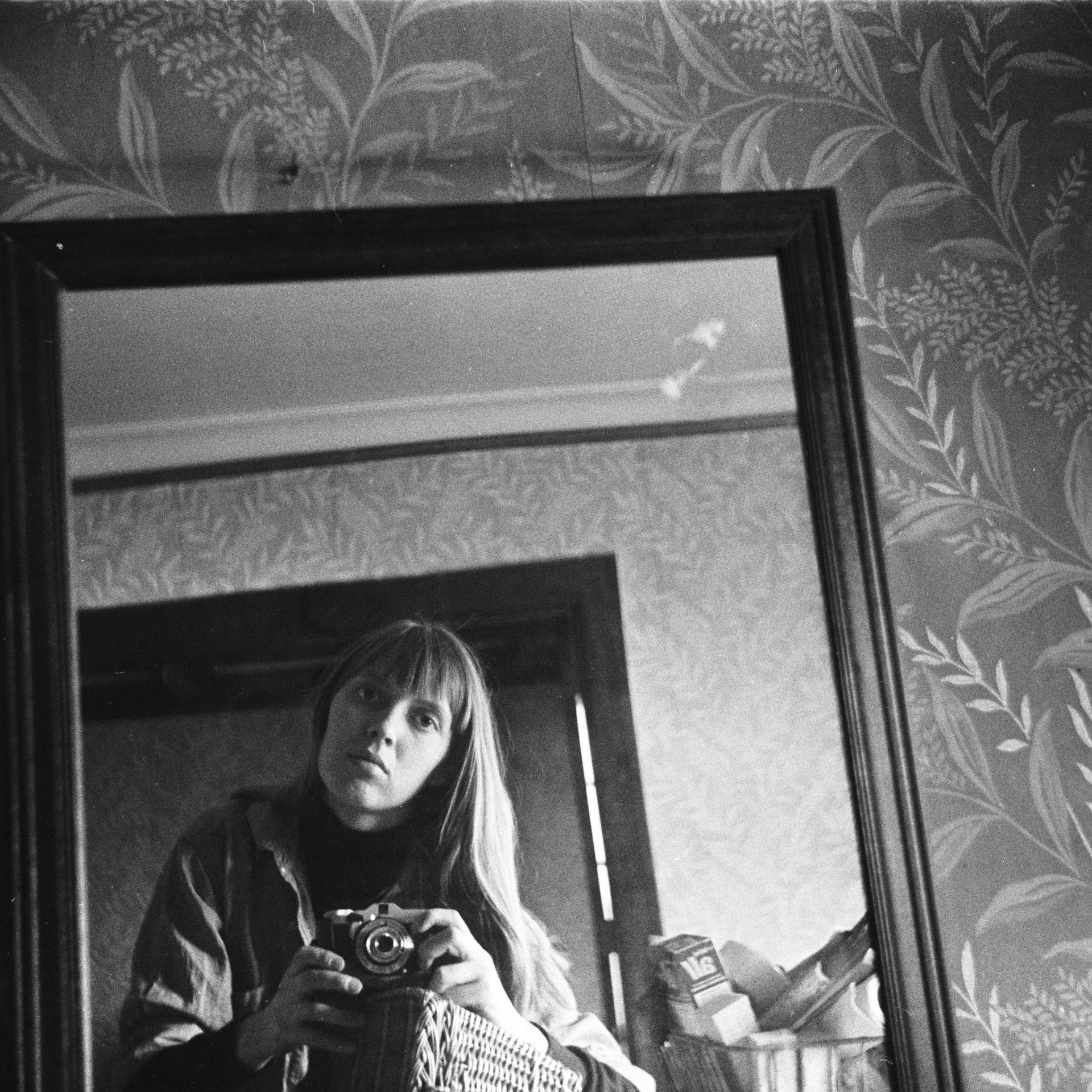

With a 35mm Taxona camera, a gift from her mother, Sinclair started shooting, documenting concerts, demonstrations, and the daily life of Detroit’s rebel generation. “Taking pictures was the most natural thing for me,” she says. Her raw black-and-white portraits often captured figures emerging from darkness, the result of what she calls “a militancy against using a flash.” Her shoots started circulating with Liberation News Service, an underground news agency that distributed press material to independent and radical publications.

“Her photography is the unconscious iconography of a generation,” says Michael Stone-Richards, professor at Detroit’s College for Creative Studies and editor of the magazine Detroit Research.

In 1964, she fell in love with the poet and activist John Sinclair. Together they founded the Detroit Artists Workshop and the White Panthers, a movement of white militants aiming to support the Black Panthers. When John was arrested in 1969 for possession of two marijuana joints, Sinclair spearheaded a two-year legal campaign for his release; it culminated in a concert featuring Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs and Allen Ginsberg. John Lennon and Yoko Ono dedicated a song to John, something Sinclair has never forgotten. John Sinclair was released three days later, on December 13, 1971. The couple had two daughters and separated in 1978.

For decades after her separation, Sinclair kept herself out of the art world, and in 1995 she moved to New Orleans, where she started printing and signing some of her most iconic photographs to sell as postcards at street markets and art festivals. She moved back to Detroit in 2000 and up until last year, it wasn’t unusual to see Sinclair at Eastern Market selling her prints.

Lately though, Sinclair’s work has seen a serious revival. From December 2014 to January 2015 she was the focus of an exhibit at Susanne Hilberry Gallery, one of the most renowned galleries in Detroit, and also had showings at art spaces in Munich and Lagos. In November her pictures of John Coltrane were published in the New Yorker, and in January she was named The Kresge Foundation’s “2016 Eminent Artist,” a prestigious award for Detroit artists that comes with a $50,000 grant. Sinclair is living on that money while she finishes a three-year project to organize and digitize the tens of thousands of images she took over the past six decades. She is also the subject of an upcoming book, Motor City Underground. Leni Sinclair Photographs 1963–1973, and The Kresge Foundation is preparing a catalogue tracing her career that will be available online.

“Leni Sinclair is no longer an underground figure,” says Cary Loren, co-author of Motor City Underground. “Shooters have been flocking to document [Detroit’s] devastating ruins and poverty, but there are just a few records of the prelude to the ruins, of the city before and during the crime scene.” Loren calls Sinclair’s photos an “important memento mori.”

Sinclair doesn’t attribute her recent successes to Detroit’s rumored revival; she actually seems wary of describing it as a revival at all. (“People are still fending for themselves, and I’m one of them,” she says.) But she is glad that the fresh attention is making it possible for her to take pictures again. “I just want to take more pictures of Detroit and its culture,” she says. “I’ll drive around, with no particular plan on where to go.”