ECB keeps pressure on euro governments and small businesses by doing nothing (again)

The European Central Bank (ECB) decided this morning to keep rates on hold at 0.75% and chose not to introduce any non-traditional measures to stimulate lending to small businesses, disappointing analysts who had hoped for monetary relief for those engines of the economy.

The European Central Bank (ECB) decided this morning to keep rates on hold at 0.75% and chose not to introduce any non-traditional measures to stimulate lending to small businesses, disappointing analysts who had hoped for monetary relief for those engines of the economy.

The lack of new policy underscores the ECB’s approach to monetary policy: it’s willing to save the euro currency, but not the underlying euro economy. Despite high unemployment, slowing industrial production, and stunningly poor outlooks for euro area economies, the ECB is sticking within its narrow mandate to defend price stability and mitigate systemic risk that could threaten the currency’s existence.

And as ECB President Mario Draghi indicated today, that will still be true even if recession begins taking hold in Germany, France, and other “core” euro zone countries, which are thought to be safe credit risks in comparison to peripheral Europe. “We see now that this [economic] weakness is extending to countries where this fragmentation is not an issue,” Draghi told reporters in a press conference today.

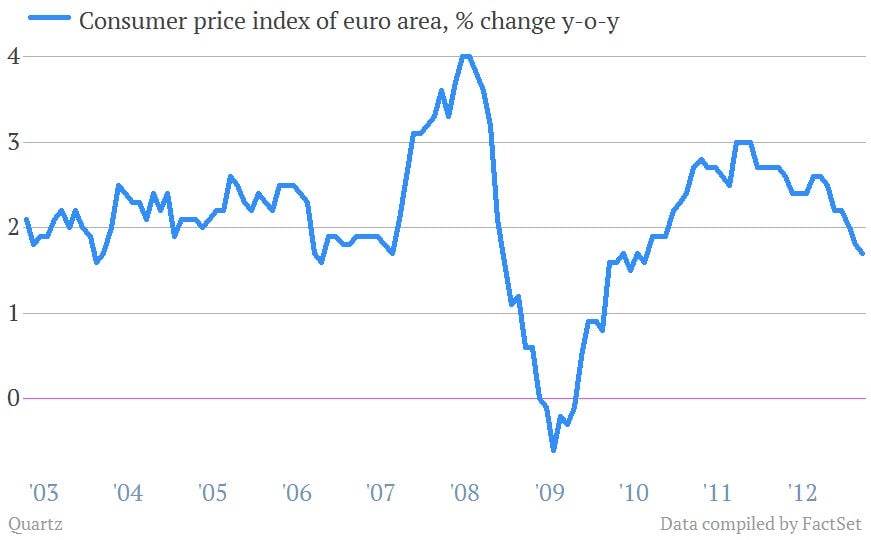

What’s more, the central bank seems more willing to endure deflation than it is to take non-standard policy measures that could test the boundaries of its mandate. Inflation in the euro area has fallen sharply in the last few months, from 2.2% in December to 1.7% in March. This is already below the ECB’s target of just under 2% inflation.

Once more, a lack of action from the ECB puts pressure on euro area governments to make decisions that will encourage growth in specific countries. This is a trick the central bank has employed repeatedly throughout the crisis: let market pressure escalate on peripheral Europe, force freaked-out European leaders to make tough decisions, and then swoop in to calm markets.

“We have to be aware of what we can do and what we cannot do,” said Draghi, even though current suggestions to support small businesses would fall squarely within the ECB’s policy tools. “We will certainly have to rely…on the intervention, on the play of other actors.”

That said, Draghi is not afraid of stepping in to dismiss rumors about bank restructurings that could shake the foundation of the euro zone’s financial system. On the management of the Cyprus bailout—in particular, a plan to throw out deposit insurance on deposits below €100,000—Draghi said it “was not smart, to say the least.” And the liquidation of Cyprus’s banks and Dutch bank SNS Real—where depositors bore losses—were “no template” for future bank failures.