Kenya is getting closer to realizing its goal of closing the world’s largest refugee camp. This week, president Uhuru Kenyatta met with United Nations secretary general Ban Ki-moon to discuss Kenya’s widely criticized decision. According to Kenyan officials, Ban told Kenyatta that the UN understands Kenya’s desire to close the camp and would seek funds to ensure the safe repatriation of refugees.

It’s not just the 344,000 refugees in the camp in Dadaab, Kenya that will be affected. Kenya will also be hit by the closure of a refugee camp that has become a hub of trade, business, and services in one of the poorest parts of the country.

1. A $14 million local economy would disappear

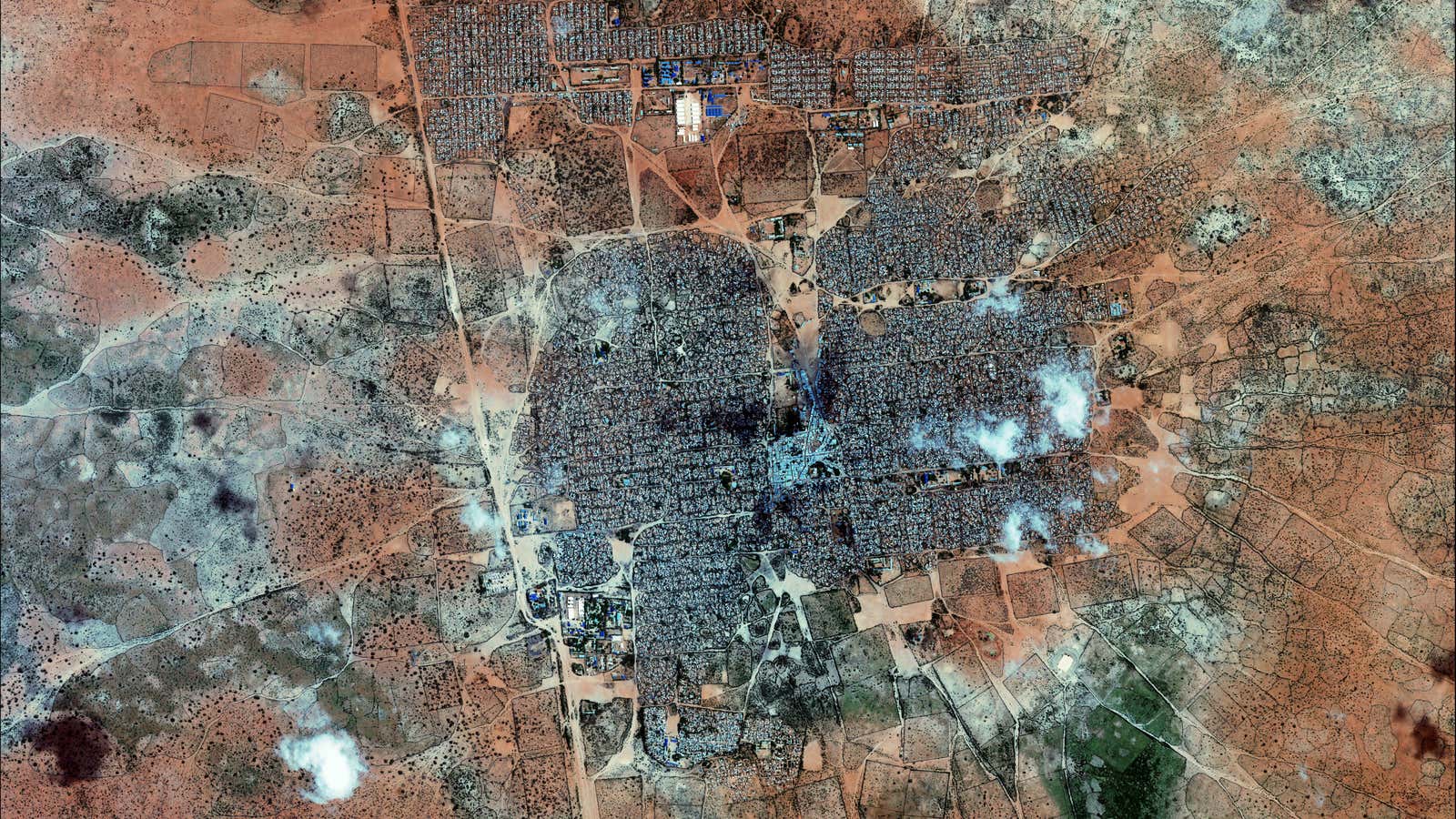

Twenty five years ago, the town of Dadaab was a small stretch of desert populated by camel and goat herders. Today, it is as large as Kenya’s third largest city and located in Kenya’s northeast, a poor and arid region that would otherwise see very little economic activity. Since 1992 when the camp was established, the local population has grown ten-fold as families have moved closer to the camp. Local pastoralists sell their meat and milk in the camp rather than walking 100km to the closest town of Garissa.

Today, more than 5,000 businesses are run from within or near the camp, including taxi companies, hotels, restaurants and small shops whose yearly turnover is estimated to be as much as $25 million (pdf, p. 39). This has had an effect on the overall local economy: wages for unskilled labor in Dadaab are between 50% and 75% higher than elsewhere in Kenya.

Altogether the direct and indirect benefits of the camp amount to as much as $14 million a year, according to a 2010 study (pdf. p. 48) commissioned by the Kenyan government, the Norwegian Embassy, and the Danish Embassy. That’s the equivalent of 25% of the average annual per capita income of Dadaab.

2. Kenyans would suffer too

Over 100,000 locals live within 50km of the Dadaab refugee camp which they rely on for schooling and free or cheaper food supplies. Over a quarter of the host population in Dadaab have ration cards while the rest benefit from the resale of donated food at cheap prices, according to the 2010 study. With 23 primary schools and a handful of secondary schools, the Dadaab refugee camp offers some of the best education in the northeast region.

“With a very significant increase in population attracted to the Dadaab area by opportunities associated with the camps, and with their livelihoods intimately dependent on access to cheap or free food and access to the markets that the camps provide, there are likely to be serious local repercussions from a future phasing out of the refugee operation in the area,” the 2010 study concluded.

3. Kenya could lose needed foreign exchange

Aid agencies working in Dadaab provide as much as 10 billion Kenyan shillings (almost $1 billion) in foreign currency to Kenya as they buy most of their supplies from local producers in Nairobi or Mombasa. (Kenya’s treasury secretary Henry Rotich has said any economic impact from closing the camp will be “very negligible,” because aid flows are no longer a major source of foreign exchange for the country.)

But other major sources of foreign reserves like tourism have been lagging as international visitors avoid Kenya out of security concerns. (The government claims the refugee camp has exacerbated the country’s vulnerability to al-Shabaab.) Flower exports, which bring in about 4 billion Kenyan shillings a year, could also suffer if a new trade deal with the European Union, Kenya’s largest buyer, is not signed in October.

4. Forced repatriation is counterproductive to the fight against al-Shabaab

According to Otsieno Namwaya, researcher in Kenya for Human Rights Watch, Kenya should be worried about the humanitarian consequences of forcing 600,000 people back to a war-torn country from which they had fled. So far, 14,000 Somalis living in Kenya have already been sent back.

He said, “This violates both Kenyan and international law… It is also counterproductive for Kenya. The returnees will become a potential recruitment ground for al-Shabaab.”