When the UK wouldn’t kill the pound for the euro, I had a funny feeling

The Brexit referendum was widely predicted to be a win for the status quo, with the UK staying in the European Union. The actual result raises many more questions than the vote was supposed to answer, and may trigger a wave of copycat exit referendums in several EU countries, with all-around bad consequences.

The Brexit referendum was widely predicted to be a win for the status quo, with the UK staying in the European Union. The actual result raises many more questions than the vote was supposed to answer, and may trigger a wave of copycat exit referendums in several EU countries, with all-around bad consequences.

A French-born naturalized US citizen, I’m a child of World War II. Conceived in Berlin where my parents worked (don’t ask), I was born in Paris in 1944, three months before allied forces disembarked in Normandy. My childhood was filled with stories about Berlin and occupied Paris, including my grandparents’ black market adventures that are amusingly (after the fact) similar to the comedy La Traversée de Paris (or Pig Across Paris, as it was known in the UK).

As a young adult, I saw Jean Monnet’s dream of a peaceful, united Europe take shape as Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, who fought WWII on opposite sides, successfully negotiated the 1963 Elysée Treaty. With this pact, Germany and France ended centuries of rivalry and established a new foundation for relations. (If you have the time and inclination, Adenauer’s life story makes for inspiring reading.)

Later still, in 1984, German chancellor Helmut Kohl and French president François Mitterrand chose the site of the 1916 Battle of Verdun for a symbolic day of reconciliation. After the customary laying of a wreath, something much less routine happened. Planned or improvised—who reached out is still a matter of debate—the two statesmen held hands in a place where hundreds of thousands from both sides died and many more were wounded.

It was a bit awkward, but deeply moving. It still is as I write this.

Step by step, we built a European Union in which people could move around without borders and use a single currency, the euro, physically (banknotes and coins) in circulation since Jan. 1, 2002. Gone were the bad old days of persnickety customs officers, currency rate games, and asking permission to move money around. While driving from Paris to a meeting in Heidelberg, the only sign that I had left France and entered Germany was a change in gas station names, from Esso to Aral.

After centuries of wars, the dream of a united, peaceful, “frictionless” (as we now like to say) Europe seemed to be coming true.

Reality, as I progressively found out, was less pretty. The EU co-opted too many too quickly, and made too many “in-but-not-totally-in” concessions. As shown in the EU Members List, Denmark and Sweden keep their own currency (in both cases the krona—same name, but not the same), as do Hungary (the forint) and Poland (the zloty).

This shows a lack of what jurists felicitously call affectio societatis: “the common will of several legal persons or legal entities to merge into one entity.” In layperson’s parlance: Some countries’ hearts weren’t entirely in the Union. For small countries, this disaffection is insignificant: Their tiny political and economical mass can’t displace Europe’s center of gravity. But the United Kingdom is the world’s fifth largest national economy, and Europe’s second.

Contentious negotiations for the UK to join the EU ended in a compromise: The country would join but keep its currency, the British pound, rather than adopt the euro.

I recall having a bad feeling when seeing this irresolution. In retrospect, and at the risk of abusing the “culture always wins“ meme, the UK’s insistence on keeping the pound was merely the first instance of the country’s strong, proud, patriotic, and sometimes isolationist culture. As time passed, the UK grew to resent deferring to a EU government whose rules and bureaucracy weren’t always clear.

Forty-three years, fueled by a migrant crisis that had stoked fear in the hearts of many Britons, the downside of EU membership was becoming more apparent. David Cameron tried to gain political advantage, strengthen his position by announcing a second referendum on EU membership—a referendum that he assumed would pass almost as easily as had the first in 1975 in which 67% voted to stay. Cooler, more enlightened voices would prevail, was the thought.

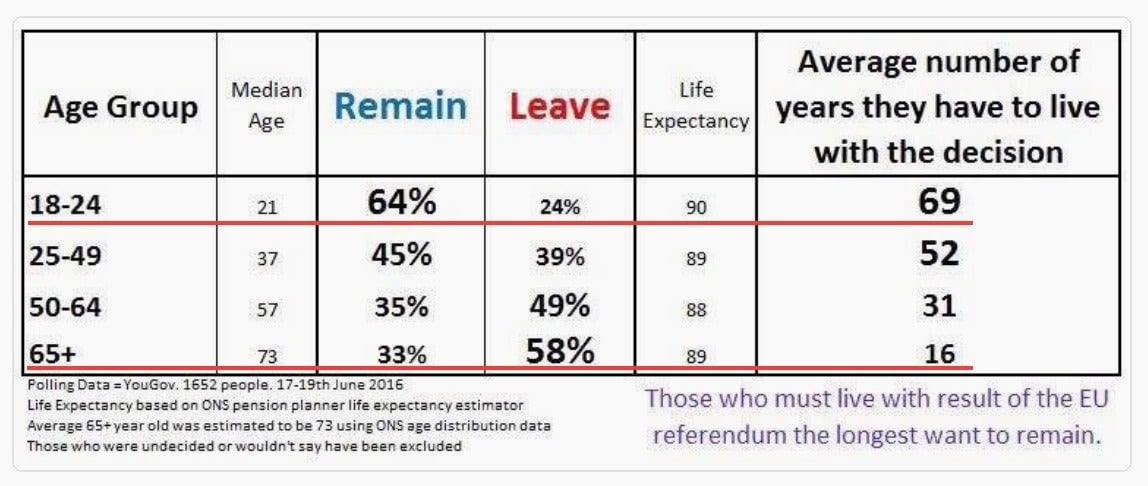

But the vote didn’t go Cameron’s way. There’s a dangerous temptation to blame older voters who have fewer years remaining to live with the decision. Behold this chart of Brexit votes by age group:

Charges of ignorance and unsophistication were hurled at the Leave camp. The more educated the voter, the more likely the vote to Remain.

According to some, less-educated voters were more susceptible to the myths that were printed in the right wing press. The Economist magazine has a chart titled “Lies, damned lies and directives“ that lists EU myths debunked by the European Commission—and there are many. (Also see the European Commission Euromyths A-Z Index site dedicated to such fear-mongering: e.g. “EU to make recycling teabags illegal,” and “Strawberries must be oval.” This surreal site sometimes loads very slowly—one wonders why—but is worth a visit.)

This gets us to another myth: Rationality. The hope is that when falsehoods are exposed, truth and reason will prevail and citizens will make the sensible, “correct” decision.

Unfortunately, another truth emerges from recent political science research [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

In a series of studies in 2005 and 2006, researchers at the University of Michigan found that when misinformed people, particularly political partisans, were exposed to corrected facts in news stories, they rarely changed their minds. In fact, they often became even more strongly set in their beliefs. Facts, they found, were not curing misinformation. Like an underpowered antibiotic, facts could actually make misinformation even stronger.

A look at another political process, closer to home, shows how pertinent this observation is.

Back in Britain, after the momentary clarity of the Brexit vote there’s now a mix of hangover, second thoughts, and wheels within wheels.

The hangover stems from a look at years of disentangling and re-knitting thousands of regulations and other agreements covering everything from education to agriculture, transportation to employment. The sudden feeling of independence soon gives way to the morose contemplation of increased friction in many walks of British life—which is why the country’s currency plunged.

This led to second thoughts. As I write this, two million Britons have signed a “do-over” petition, arguing that the Brexit referendum was merely advisory, and that the UK government is at liberty to not invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty which sets the clock ticking.

The petition is well-intentioned, but unlikely to work. Disagreeing with a clear popular vote, ill-informed or not, is one thing; undoing it would only lead to deeper division. Speaking of division, Scotland is considering a referendum to leave the UK and join the EU, an idea that has received nearly 60% support according to a recent poll.

The epicycles and the convoluted calculations started right away. David Cameron resigned instantly, with effect in October, but didn’t say if or when he’ll invoke Article 50. Opponents see this as a clever maneuver to offload the Leave consequences onto Boris Johnson, Cameron’s putative successor, and thus torpedo Johnson’s political career. On that theory, see this comment on The Guardian’s website, eloquent but too long (561 words) for inclusion here.

Outside the UK, computational wheels are turning just as fast. EU president Martin Shulz wants Britain out as soon as possible, a sentiment echoed by many European leaders—with the exception of Kanzlerin Merkel who calls for a deliberate process.

The fear is that a protracted, messy separation will cause severe harm all around, and that the UK will use the threat to strong-arm the EU into costly concessions.

We’re in a mess—an unstable one.

As I contemplate my naive old dreams of a united Europe, two thoughts float to the surface.

First, the UK Leave victory might cause an avalanche of isolationist, nationalist, sovereignist votes across other European countries—votes to leave altogether, abandon the euro, or renegotiate the terms of EU membership.

Second, when voters feel disenfranchised, ill-informed or not, disrespecting them leads to convulsions—such as those that we’re experiencing in our country.

Well-meaning people on all sides insist that reason should prevail. Sure. But why start now?

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.