Brexit is like a burglary when it comes to the tech and venture capital industries

Britain’s vote to leave the EU will send ripples through the tech world—mostly negative ones. As for the media establishment, it should pause and reflect on its responsibility in this historic accident.

Britain’s vote to leave the EU will send ripples through the tech world—mostly negative ones. As for the media establishment, it should pause and reflect on its responsibility in this historic accident.

The Brexit feels like a burglary. As time goes on, you keep discovering what has been lost. On June 24th, the European tech world had a rude awakening; it affected the British tech community at first, one that was massively opposed to the UK leaving the EU (87% favored Remain). Right after the referendum, everyone began a Brexit damage assessment.

Four areas are impacted: day-to-day management of start-ups, and access to capital, talent, and customers.

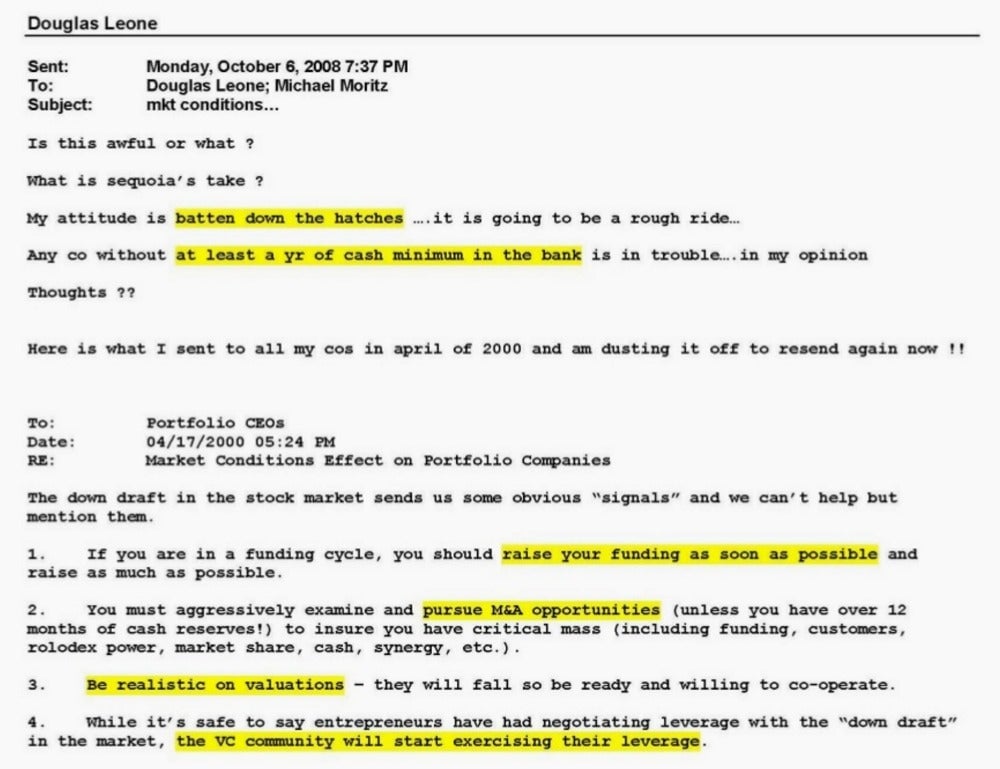

A slide deck made by the Californian investment firm Sequoia Capital right after the Lehman collapse of 2008 will help illustrate Brexit’s impact on startups. Called “R.I.P. Good Times” and unearthed by Recode last Friday, the deck’s recommendations boil down to the following: Reduce. Across the board. ASAP.

I selected this slide revealing an email from Douglas Leone, a Sequoia partner:

To be sure, the Brexit doesn’t have a scope nor the brutality of the 2008 financial crisis (nor, for that matter, of the 2000 tech implosion). Still, a severe downturn is expected in hiring, engineering, and marketing expenditures.

When it comes to access to funding, the UK used to be the center of gravity for the European VC community. In one large capital funnel, it combined a large and global banking system, culture, and know-how. This is not the case for Germany or France. For the latter, several high-profile startups such as BlablaCar or Sigfox scaled up thanks to massive UK-originated funding unavailable locally. Now, such UK funding might become much more difficult to bring about.

Who will pick up the pieces? Unclear. Certainly not France, whose tax system is notoriously averse to funding and scaling innovation. In a worth-reading story published last December by the Guardian, “In search of a European Google,” David Galbraith, partner at venture investment firm Anthemis pointed out a peculiar orientation of the Gallic tax code:

Look at France: if you buy a painting, and sell it for a profit, there’s no capital gains tax paid on the profit, because the French government wants to use the tax system to encourage ownership of art. But, if you buy, say, a domain name and sell it for a profit a decade later, capital gains tax is still due. (…) The cultural differences between Europe and the rest of the world may ultimately be why no Google, Apple or Facebook has come from the lands that gave us the telescope, the steam engine and the printing press. This is a sickness in Europe. The past is valued more than the future.

One could add: Paintings and other art objects are exempt form France’s (in)famous “wealth tax,” the ISF. But, depending on the size of their ownership and other conditions, entrepreneurs might be taxed on the value of their shares.

This won’t get better anytime soon. See how French finance minister Emmanuel Macron—probably the French political establishment’s most promising individual—is stigmatized each time he promotes individual ambition or entrepreneurship.

For Europe, the quality and cost of talent were considered strong advantages when compared to the United States. I could name many startups who gladly keep a large technical setup in Europe because a qualified workforce is much less expensive than in Silicon Valley, sometimes by a factor of two, and is more loyal to boot.

In the UK, prime minister David Cameron came under fire last year when he outlined a plan to curb immigration of skilled workers. More than 200 startups’ CEOs, including big names such as Lastminute.com, TransferWise, and Shazam, wrote him:

The UK has become a global tech hub thanks in large part to start-up founders, investors and employees from across the globe, including many of us who were not born in Britain but choose to invest our time and skills here. (…) We call on you to ensure that any future changes to the immigration system make it easier, not harder, for qualified digital entrepreneurs to come to the UK to start their business, and for growing start-ups to hire top international talent.

Because the Brexit has been won mostly on anti-immigration sentiment, the idea of clamping down the influx of skilled workers will come back with a vengeance. Beneficiaries of this anti-foreigner attitude include former Eastern block countries where tech companies already outsource coding and engineering.

Still, the Brexit-fueled unfavorable climate for tech startups in the UK will take time to manifest itself. To start with, Boris Johnson, most likely the next British prime minister, wants to avoid a Pyrrhic victory. A wily opportunist, as opposed to a hardcore believer, Boris Johnson will be careful to preserve the fabric of British tech entrepreneurship. Second, severing 43 years of administrative ties between the United Kingdom and the rest of the EU won’t be easy: there are 80,000 pages of commercial agreements that will take years to unwind. Whether they work in tech or not, 300,000 French who live in the UK—London is France’s “sixth largest city”—will remain while their employers reassess their presence, a process that might take a long time, as the Brexit’s next steps are anything but clear.

Showing its disconnected arrogance, the media sphere had stayed inside its “Europe-ist elite” bubble.

The Brexit vote also attests to a growing disconnection between the ruling elite and the rest of the population. In the hours that followed the referendum’s results, pro-European media were deriding the surge of Google queries asking about the exact meaning of Brexit, suggesting that most of those who voted out didn’t know what there were doing. It might be true (and appalling), but above all, it should trigger a serious introspection on the role of a media sphere that basically failed to explain the benefits of the European Union to skeptics. It was the case in the UK and in France. In both countries, the elite treated the slightest questioning of the European dogma with undisguised contempt, rather than understanding (which doesn’t imply agreement) and providing information.

Last December, L’Opinion, the French conservative daily, published an op-ed written by former foreign minister Hubert Vedrine, one of the strongest advocates of the EU—who also never lost his clarity of mind. Here is a short abstract (translation’s mine):

[The European Project] comes from the will of the elites, ranging from right to left, and carried out for decades “in the interest of the populations”—but without them. (…) The patronizing and authoritarian catechism of the europeists stated that the only way for Europe was to move forward [despite what Vedrine describes a string of referendum rejections]. Even worse, those who disputed any part of [the EU project] or were defensive of their identity, the skeptics, the disappointed were thrown in the camp of the true euro-hostiles, insulted, categorized as selfish, nationalists, sovereignists, without even a shred of a discussion. (…) The divide between the europeist elite and the populace then became problem number one.

As Hubert Vedrine suggests, the media elite that thrived on the euro-ideology stifled the debate, and avoided any form of challenge.

European blunders are, unfortunately, numerous. The EU didn’t live up to its hopes and promises on many issues. To name but a few:

- Failure to create a European educational system: Nearly 30 years after the introduction of the Erasmus Program, only 1% of European students actually go and study outside of their own country. There is not a single European-size university.

- Multiple failures building a convergent diplomacy supported by a comprehensive defense apparatus: This has proved tragic in many crises, ranging from the Balkans War in the 1990s to the current refugee crisis, and let’s not forget the inability of Europe’s diplomacy to counter-balance George W. Bush’s obsession with Iraq, which eventually paved the way to Daesh.

- Failure to create vast, ambitious, forward-looking projects in science or medicine. We would all have dreamed of an Apollo-size program to deal with cancer or to foster innovation in unchartered fields. Instead we have Margrethe Vestager, the European commissioner for competition, who employs a gigantic bureaucracy of 900 staffers whose main goal is to snatch Google’s scalp—but notoriously failed to tame Big Pharma, among other shortcomings.

- Failure to properly manage the Schengen space. That project was based on the noble idea of removing border control. Unfortunately, because there is no such thing as an integrated European intelligence body, the Schengen project suffered from an inability to monitor its external borders, leaving Europe’s doors open to terrorists.

The Brexit is a terrible accident in the European journey. The vast majority of the young Brits who wanted to remain in the EU will pay a terrible price. But it is now mostly UK’s (big) problem. The rest of the continent will weather this as it always did. Brexit’s only benefit to the rest of Europe will be to trigger a necessary soul-searching for the underlying causes of this unfortunate event.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.