Ever since word got out that Bourne and Shepherd, the 176-year-old photo studio in Kolkata, had shut down, proprietor Jayant Gandhi has been a busy man. Busier perhaps than his last few years at the legendary establishment, which was the world’s oldest functioning studio of its kind, until it quietly stopped functioning on April 20.

“Every day I receive calls for interviews,” said Gandhi. “I meet scores of people who ask me the same things and I always have the same answers. I had nothing to do at the studio anymore. There weren’t any customers I could talk to either. The world over, photography, especially artistic photography, is dying out. There is no future in it anymore.”

Gandhi is seated in a spartan drawing room in a sleepy south Kolkata neighbourhood. Around him, there is no visible link to the history he had been a part of till recently. Only a cricket bat trophy—one of his sons is cricketer Devang Gandhi—and images of spiritual gurus. And the dry, almost dark, humour of a man who recounts the last few weeks to the shutdown that has the world media calling him up for stories, sharing memories, hunting for memorabilia.

Gandhi, in his 70s, is amused at the outpouring of nostalgia, grief, and obituaries from photographers, artists, and regulars. “I received a phone call from London, one from Bangalore, from people who say they want to do something about the studio, revive it perhaps,” he said. “I understand people are suddenly very emotional, but it is one thing to show solidarity from a distance and a different thing to be here and deal with the reality.”

There is understandably a devastating pragmatism about him, a man who has fought a lonely war for more than two decades. The studio that survived political and social turmoil, and many changes in ownership through the years (the last British owner left in the 1930s), actually died twice over. In 1991, a fire destroyed most of Bourne and Shepherd’s archival material, a setback from which it could never recover. It was perhaps the beginning of the end, as the turn of the century brought digital photography and later smartphones and social media. The fine art of studio photography, black-and-white prints and colour portrait prints developed painstakingly by experienced studio hands, could not tackle the combined firepower of the electronic and internet juggernaut.

“In 1991, when the fire broke out, the chief minister sent someone to find out the extent of our losses,” he said. “That was the last time anyone ever asked about us.”

Even before the Supreme Court ruled against the studio in a 14-year-old legal wrangle with the landowner—Life Insurance Corporation of India—Gandhi had been quietly preparing for a dignified exit. “We shut down in the midst of the [state] elections,” he said. “No one, expect the few remaining staff knew about it. When suppliers from Nikon and Canon visited our store, they were surprised to see empty shelves. I deflected their attention somehow, saying we will restock in the new financial year. I had been preparing for a month. I did not want to meet anyone before I had locked out.”

Gandhi began by moving out some of the antique large format wooden body cameras and glass plates from the premises. He has no idea of what he would like to do with them, but, as of now, he has kept them away from treasure hunters and curiosity shoppers.

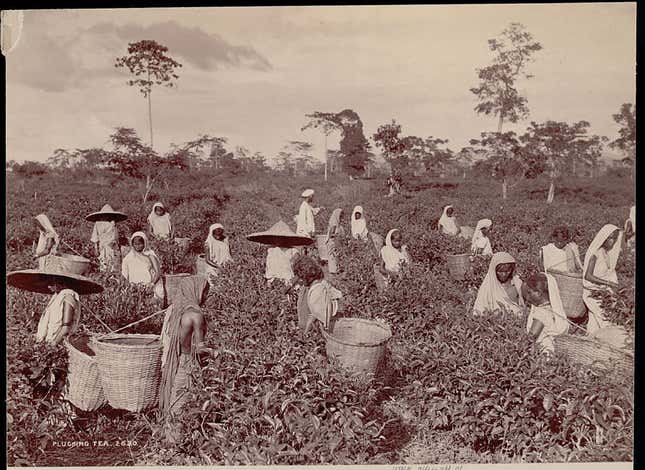

Established in 1863, Bourne and Shepherd was one of India’s most successful commercial studios in 19th and 20th centuries, with cultural, political icons, celebrities and ordinary citizens thronging its elegant colonial building for their signature portraits. It had a branch in Shimla, though its photographers travelled widely through the subcontinent.

“Portraits were our strength,” said Gandhi, adding how photographs for matchmaking formed a significant chunk of the business till a decade or so ago. “There was a time when Bengali families had to get a pretty picture of their daughter clicked for the matrimonial agencies. There were no cameras at home and where else would you go but to the studio? After they got married, they would come to the studio for a couple-photograph.” Over generations, the studio forged bonds with families.

“We never retouched any of our photographs. Not even for the matchmaking shoots,” he said. “Why mislead people with a picture and then create problems for them when they meet the person and raise issues over skin tone? Now with smartphones and photo shopping tools, anything is possible.”

Gandhi, who was born in Bhavnagar in Gujarat and came to Calcutta when he was five years old, took over the studio in 1964 and kept it running with his maternal cousins. “Since then we tried a lot of things, expanded out work,” he said. “We did industrial and commercial photography. We turned to colour photography in the early ‘90s. We tried to adapt to changes. Till the last few years… except selling of equipment and paraphernalia, there is no money in photography business. There too people prefer to buy online where they compare prices and get it for cheap. Developing and printing too does not make any business sense because people are only storing on hard drives or online.”

The studio’s golden run was sometime in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when a team of 30 in-house photographers would be sent on regular, prestigious assignments.

Gandhi, who is held in high esteem by those who swear by his knowledge of equipment and photography, never took up photographic assignments, but preferred to build relationships with his customers. “I belong to that school of thought that treats its customers with utmost respect,” he said. “Even if they do not end up buying anything, they should have a good experience at the studio. A positive word-of-mouth publicity is the best you can get in this business.” The philosophy, along with the art of photography, was severely tested in the world of impersonal shopping malls and ill-informed staff.

From a bustling studio spread over three floors, the hive of activity at Bourne and Shepherd reduced over time to the ground floor with six old-time staffers. “They knew we are about to shut down,” said Gandhi.

“Some of them had been with me for three decades and more,” he said. “I told them they would get their dues, but they had to bear with me until I sorted out the paperwork. They still call me to find out if I am doing all right. It feels good.”

The phone is buzzing as more interview requests keep coming in. Gandhi has the same things to say to everyone. But on a parting note, he recounts the story about the legal representative who arrived to oversee the closure of the studio, with 14 locks in tow. Gandhi welcomed him, made pleasant small talk before granting the star-struck young man his one last wish. “May I please take a photograph with your staff in the studio?’” he pleaded. Gandhi smiled and said, “Why not?”

As always, Gandhi was not in the frame. For the man who was synonymous with a piece of photographic history, there are no pictorial records to be found anywhere. Except perhaps in his passport.

“I am stoic about the closure because there is no point getting worked up over the inevitable,” he said. “Trust me, the brouhaha is going to die down in a month. No one will remember… people move on. Maybe I will too.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.