African migrants are returning from China and telling their compatriots not to go

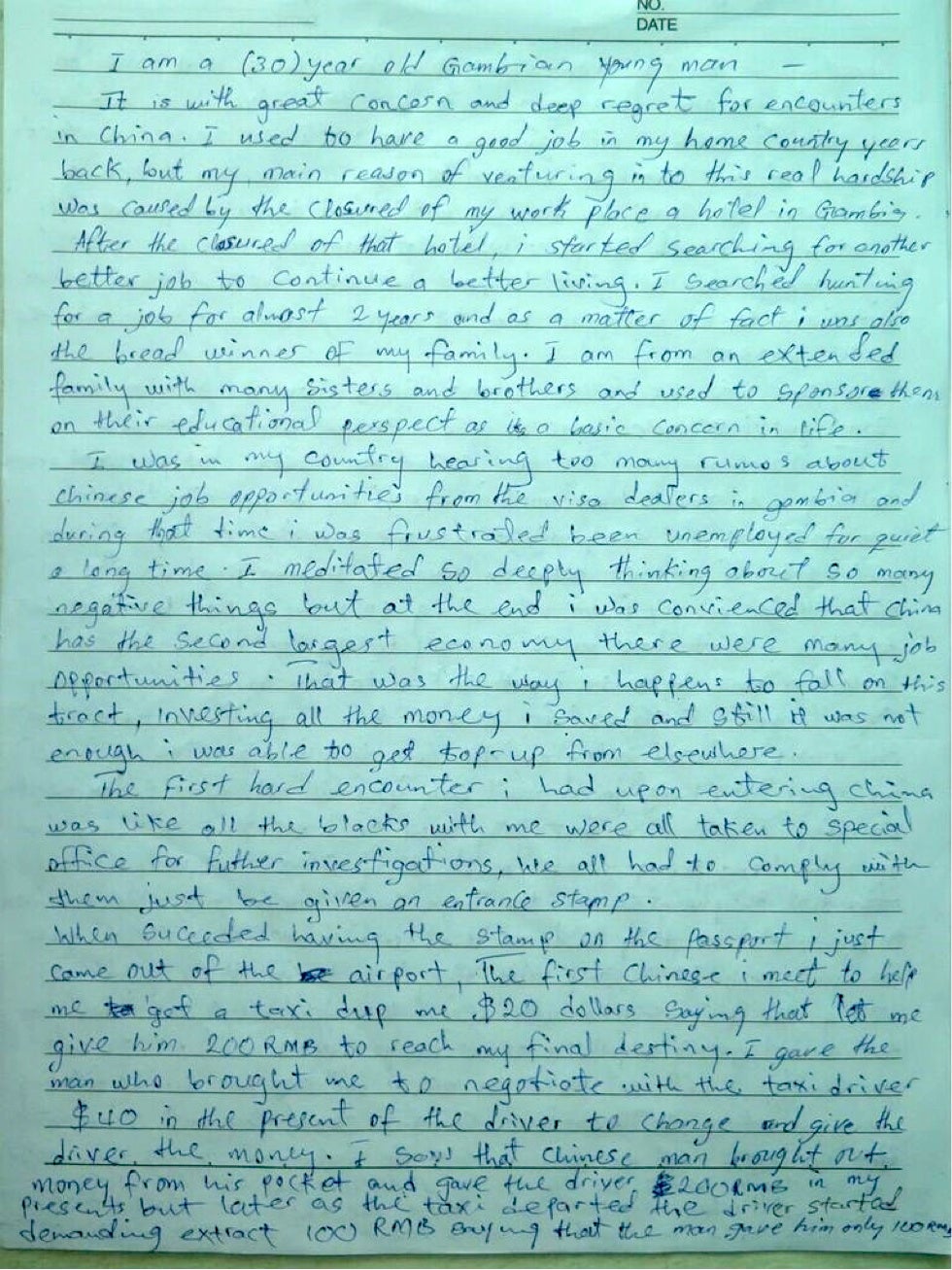

When Lamin Ceesay, an energetic 25-year-old from Gambia, arrived in China last year, he thought his life had made a turn for the better. As the oldest of four siblings, he was responsible for caring for his family, especially after his father passed away. But jobs were few in his hometown of Tallinding Kunjang, outside of the Gambian capital of Banjul. After hearing about China’s rise, his uncle sold off his taxi business and the two of them bought plane tickets and paid a local visa dealer to get them to China.

When Lamin Ceesay, an energetic 25-year-old from Gambia, arrived in China last year, he thought his life had made a turn for the better. As the oldest of four siblings, he was responsible for caring for his family, especially after his father passed away. But jobs were few in his hometown of Tallinding Kunjang, outside of the Gambian capital of Banjul. After hearing about China’s rise, his uncle sold off his taxi business and the two of them bought plane tickets and paid a local visa dealer to get them to China.

“It was very developed. The tall buildings, everything was colorful. I thought, okay my life is going to change. It’s going to be better. Life is good here,” Ceesay tells Quartz, describing his first impressions of the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou.

Gambia, a small country of just under 2 million people in West Africa, has been losing entire villages to migration mostly to Europe, but also to China. Chinese border restrictions have been easier than in Europe or North America. Guangzhou has become a hub for African migrants, traders, and entrepreneurs. In Gambia, youth unemployment is high, almost 40%, encouraging people like Ceesay to look east.

“All I knew is that China was a world-class country and the economy is good,” he says.

But Ceesay’s new life didn’t turn out how he imagined. The job visa dealers promised would help him pay off his debts in three months didn’t exist. Ceesay struggled even to feed himself. When he tried to move to Hong Kong where he had heard work was better, he was escorted back to Guangzhou by police. Ceesay ended up in Thailand for three months, unsuccessfully looking for work, before coming home.

Determined not to let his experience be in vain, Ceesay has turned into a campaigner against the myth of China as a promised land for Africans seeking work. “I told my uncle, I’m going back to Gambia, and I’m going to tell this story and explain what’s happening.”

Ceesay went on local radio shows answering questions from callers about life and work in China. He started a Facebook page, “Gambians Nightmare in China” detailing the frustrating and dangerous situations that he and other Gambians in China found themselves in. Now, his story along with those of other returned Gambian migrants, is the basis of a new website called Uturn Asia, done in collaboration with migration researchers, Heidi Østbø Haugen and Manon Diederich, from the University of Oslo and the University of Cologne.

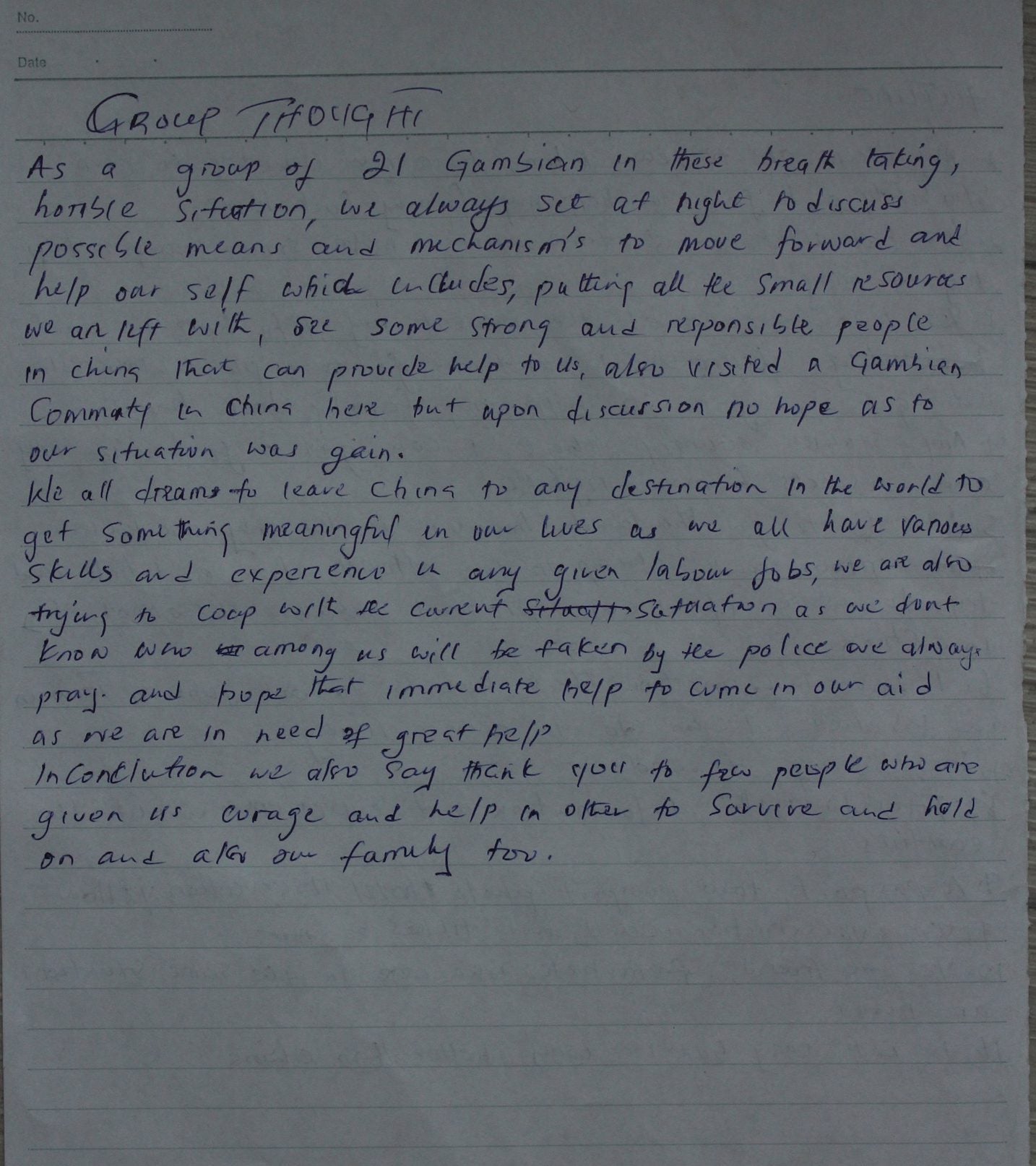

“The project came about because they had a strong wish to warn others against coming,” says Østbø Haugen. “They thought they could do so more effectively as a group than as individuals, as individual accounts of failure are often written off as attempts to justify ineptness.”

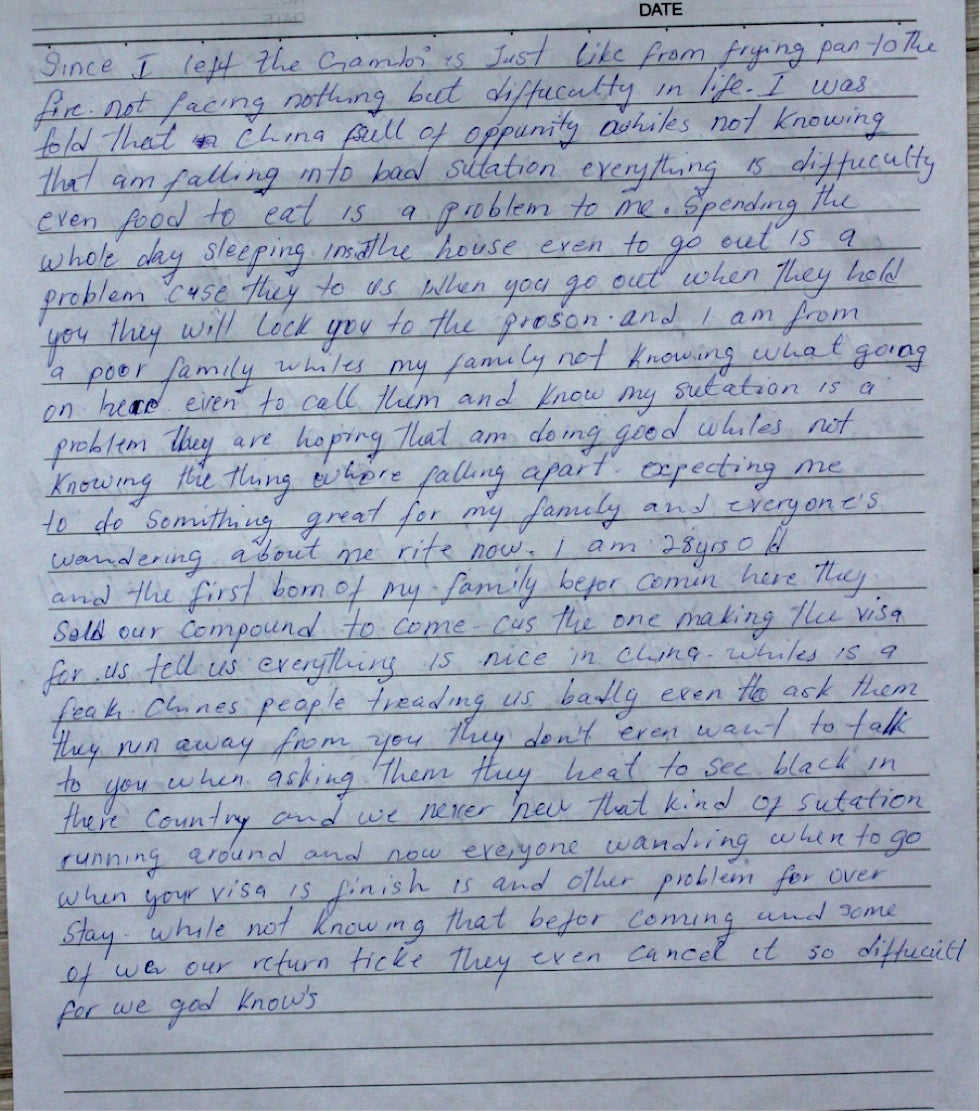

On the website, Ceesay and others detail the full circle, or U-turn, they completed: the decision to leave home—a calculus that often meant taking on heavy loans, spending years of saving, or selling off their few assets—optimism replaced by desperation as they ran out of money in China, and humiliation as they tried to scrabble enough money together to go home.

“The dream that you hoped for—the better job, better life— is not there. It’s just a dream that is nowhere to be found in Asia,” Ceesay says.

Ceesay’s warning is for other African communities, many of whom have had similar experiences. “What happened to them has happened to Africans of other nationalities earlier,” says Østbø Haugen. “But their desire to prevent others from ending up in the same situation is unique.”

In fact, China’s African population may already be shrinking. (Researchers say the concentration of Africans in Guangzhou better known as “Chocolate City” is dispersing.) Estimates for the number of sub-Saharan Africans in Guangzhou range from 150,000 long-term residents, according to government statistics last year, to as high as 300,000—figures complicated by the number of Africans coming in and out of the country as well as those who overstay their visas.

As China’s economy slows and stricter visa requirements have been put in place, researchers say more African migrants are opting to go home. Others experience everyday racism like taxi drivers who won’t pick them up.

The Gambian accounts on Uturn Asia depict a hard life for Africans in China. They describe living in cramped apartments where they have to take turns sleeping because there aren’t enough beds. Many spend their days hiding inside, afraid of being caught by the police with expired visas. Several detail struggling to get enough water and food in one of the most developed cities in China.

There are also examples of people coming together. Ceesay helped organize food supplies for a group of 20 Gambians, all in similar situations as him, by asking each to contribute 5 yuan (about $0.75) a day for food supplies. Africans from other countries also showed solidarity.

“The solidarity of West Africans never stops to amaze me,” says Østbø Haugen.”They shared the food and water someone had money to buy, and African cooks of other nationalities gave them left-overs after their informal restaurants closed.”

It’s unclear whether the project will do much to change the combination of desperation and hopefulness that motivates many to emigrate. Several of those interviewed for the project went on to migrate “the back way” to Europe, by crossing the Mediterranean, a dangerous sea journey that killed 4,000 migrants last year. One of the interview subjects considered moving back to China but decided to go to Europe instead. He died during the crossing, according to Østbø Haugen.

Despite years of arguing with his younger brother and describing his own experience in China, Ceesay’s younger brother also left home for Europe two weeks ago, traveling to Libya where Ceesay last heard from him.