It is Beijing’s fault that China lost big in the South China Sea ruling

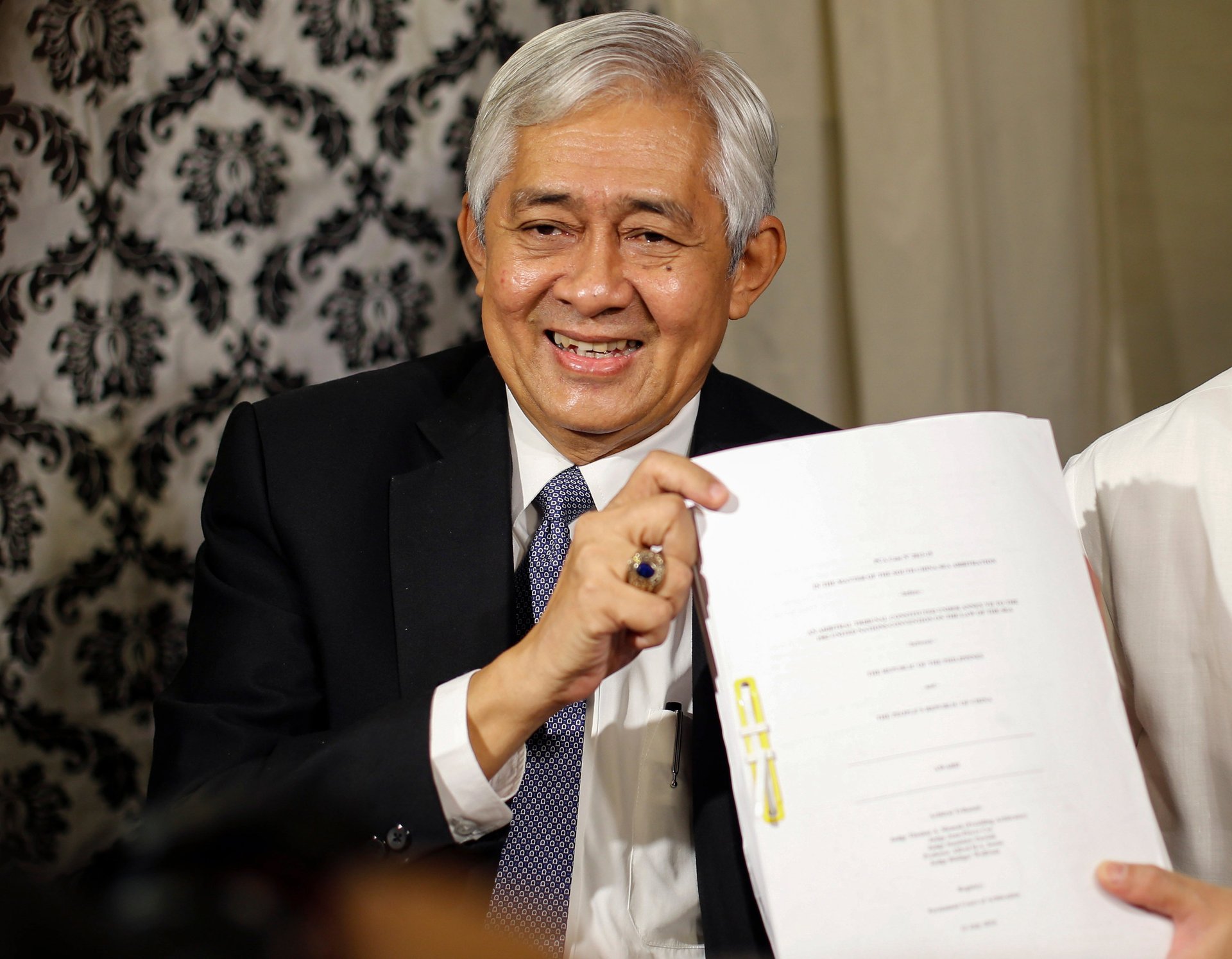

The award issued last week by an arbitral tribunal sitting in The Hague can only be described as a tremendous legal victory for the Philippines over China. The tribunal, which was formed pursuant to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ruled in favor of the Philippines on 14 of 15 claims. On every issues of substance, the tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines. Few experts who followed the award closely had predicted such a sweeping, one-sided result. I certainly did not.

The award issued last week by an arbitral tribunal sitting in The Hague can only be described as a tremendous legal victory for the Philippines over China. The tribunal, which was formed pursuant to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ruled in favor of the Philippines on 14 of 15 claims. On every issues of substance, the tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines. Few experts who followed the award closely had predicted such a sweeping, one-sided result. I certainly did not.

But taking a step back after reviewing the award, perhaps I should not have been surprised. China’s legal arguments for maritime rights in the South China Sea were always weak since the Chinese mainland is much farther away than any of its neighbors. China exacerbated these weaknesses by refusing to participate in the tribunal in any way, and then launching a global public relations campaign that dramatically heightened the award’s significance in the eyes of the global media.

In the award, the tribunal ruled that China had violated its obligations under UNCLOS in a variety of ways. First, the tribunal held that China’s nine-dash-line claim, which refers to a line delineating some form of Chinese sovereign rights over nearly 80% of the South China Sea, was inconsistent with China’s obligations under UNCLOS. Whereas the treaty requires all states to limit maritime rights to certain distances from land, the nine-dash line represented a broad claim to “historic rights.” China may well have had historic rights to fishing in the region dating back centuries, the tribunal ruled, but it gave up such rights when it agreed to join UNCLOS in 1996.

In return for joining UNCLOS and giving up its historic rights, the tribunal noted, China gained internationally recognized exclusive economic zones (EEZs) stretching out over 200 nautical miles from its mainland coasts and islands. Without UNCLOS, the tribunal pointed out, China would not have had such broad, internationally recognized maritime rights near its mainland coast and islands.

Second, the tribunal found that none of the land features claimed or occupied by China in the Spratly Islands (a group of land features near the Philippines) are actually “islands” as defined by UNCLOS. This means that even if China has sovereignty over all of the land features in the Spratlys, China cannot claim rights to control fishing and undersea hydrocarbons under an EEZ because there are no “islands” as defined by UNCLOS in the whole Spratly region.

Such EEZ rights thus default to the Philippines because much of this area lies within 200 nautical miles of the main Philippines islands. To be sure, the tribunal found that (contrary to the Philippines’ arguments) several land features do constitute “rocks” rather than simply “low-tide elevations.” So China could potentially claim 12 nautical miles of territorial seas around those rocks if it could establish sovereignty over them.

But the tribunal’s award makes it legally difficult for China to make a sweeping claim to sovereignty over both the land and the maritime zones in the Spratlys. It also calls into serious question the legality of China’s construction of an artificial island on Mischief Reef, which the tribunal held was merely a “low-tide elevation” incapable of generating even a 12 nm territorial sea.

Finally, the tribunal also ruled that China’s construction of artificial islands has caused “irreparable” damage to the region’s environment. Whether or not China has sovereignty over the land features, the tribunal held China had violated its UNCLOS obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment. China further violated its obligations to allow Filipino fisherman to enter their traditional fishing grounds and to avoid harassing or obstructing non-Chinese fishermen in the region.

It didn’t have to be this way

All of this constitutes a stunning across-the-board legal victory for the Philippines. Moreover, the award will only damage China while benefiting Southeast Asian states like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which are far less likely to base their maritime claims on sketchy underwater land features.

All of those nations, like the Philippines, have undisputed sovereignty over mainland coastlines that can generate broad maritime rights. China, whose mainland coast is 600 miles away, has to rely on land features that it does not even control and that are too small to generate maritime rights. Because China is the only state vulnerable to this type of legal attack, the other claimants will not hesitate to invoke the tribunal’s award since it will be unlikely to backfire on their own claims.

So now China finds itself on the losing end of a damaging arbitral award. But it didn’t have to be this way. In my view, China made two fateful mistakes in responding to the Philippines’ lawsuit. First, from the outset, China decided it would neither accept nor participate in the arbitral tribunal process. This meant that China gave up its right to appoint one member of the arbitral tribunal of its own choosing, and to participate and influence the appointment of three others.

Because of China’s boycott, the task of appointing four out of five members of the arbitral tribunal fell (pursuant to the treaty) to Shunji Yanai, the then-President of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. While Yanai’s appointments were all experienced, credible international lawyers with deep expertise in the legal issues of the case, none was particularly sensitive or favorable to China.

China’s boycott also meant that China made no written submissions to the tribunal, and did not participate in oral hearings. From a legal point of view, this hurt China’s case because it could not fully present the substance of its arguments in a detailed form that could be legally persuasive, while its opponent filed thousands of pages of written documents. It also could not orally answer specific questions the tribunal had that might have influenced the final decision. While the tribunal made every effort to figure out China’s views from public statements published on the internet, there is little doubt that China’s case was hurt by the fact that no one actually presented it in a rigorous legal form.

Finally, China exacerbated the significance of the award by launching a global public relations blitz in the months leading up to release of the tribunal’s award. Most international tribunals operate in deep obscurity, especially in the United States. Media coverage is dutiful, but rarely comprehensive, because most international arbitral awards seem technical, dull, and unenforceable. The US government’s refusal to carry out an order from the International Court of Justice in 2008 barely rated a single day’s news coverage.

But China’s blizzard of editorials, op-eds by Chinese ambassadors, joint declarations with obscure foreign leaders, and Chinese civil society statements of support drew the attention of the global media like nothing else could. Such media gave foreign governments and NGOs a platform to opine on the importance of the award. When China reacted with clearly hostile and nearly frantic language, the global media had found its story. China, the newly risen power, was risking its global reputation in a now landmark international law ruling. Such a story, complete with China’s angry denials, was too good for the global media to resist.

Beijing has indicated it will simply ignore the award, and UNCLOS has no mechanisms for enforcing compliance with its awards. But China’s global image has suffered a serious blow. China promised in UNCLOS to allow an arbitral tribunal to conclusively settle any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of the treaty, including whether such a tribunal has jurisdiction to hear the dispute. Once such a dispute arose, China boycotted and then tried to denigrate through a global publicity campaign the entire legitimacy of a widely accepted international treaty regime. And by refusing to comply, it has now reneged on that promise and damaged its image among its neighbors and partners around the world.

It is not an irreversible situation, but it was an avoidable one.

You can follow Julian on Twitter at @julianku.