The line on a 70-year-old map that threatens to set off a war in East Asia

Tensions are escalating in the South China Sea. On July 12 a UN tribunal will deliver a long-awaited verdict on Beijing’s sweeping claims to the vital waterway. Each year more than $5 trillion in trade passes through the sea, which contains rich fishing grounds and large, mostly untapped reserves of oil and natural gas.

Tensions are escalating in the South China Sea. On July 12 a UN tribunal will deliver a long-awaited verdict on Beijing’s sweeping claims to the vital waterway. Each year more than $5 trillion in trade passes through the sea, which contains rich fishing grounds and large, mostly untapped reserves of oil and natural gas.

China says it has a historical claim to virtually the entire sea. The other countries on the sea’s perimeter argue China is violating international treaties, infringing on their fishing and exploration rights, and staking out military positions that could give it the edge in a future conflict. How the tribunal rules, therefore, will influence everything from trade to defense to political relationships—and perhaps wars. “The South China Sea issue is one of the most important global issues right now,” says Anders Corr, founder of Corr Analytics. “It’s a tinder box.”

At the center of China’s claims is a curious, dashed-line map drawn up in the 1940s. Knowing its story is essential to understanding how China and its neighbors will behave in the years to come.

A sweeping claim

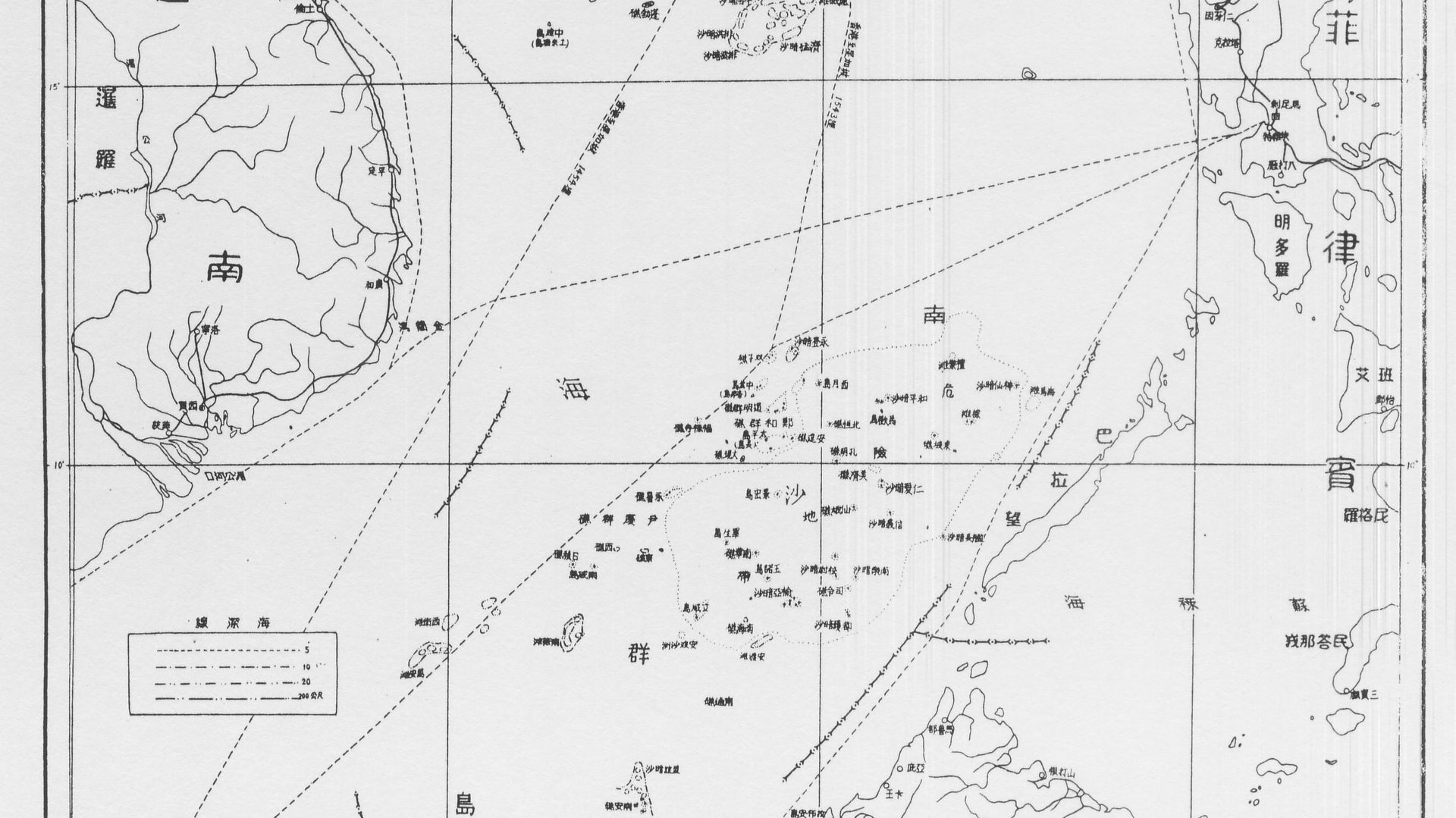

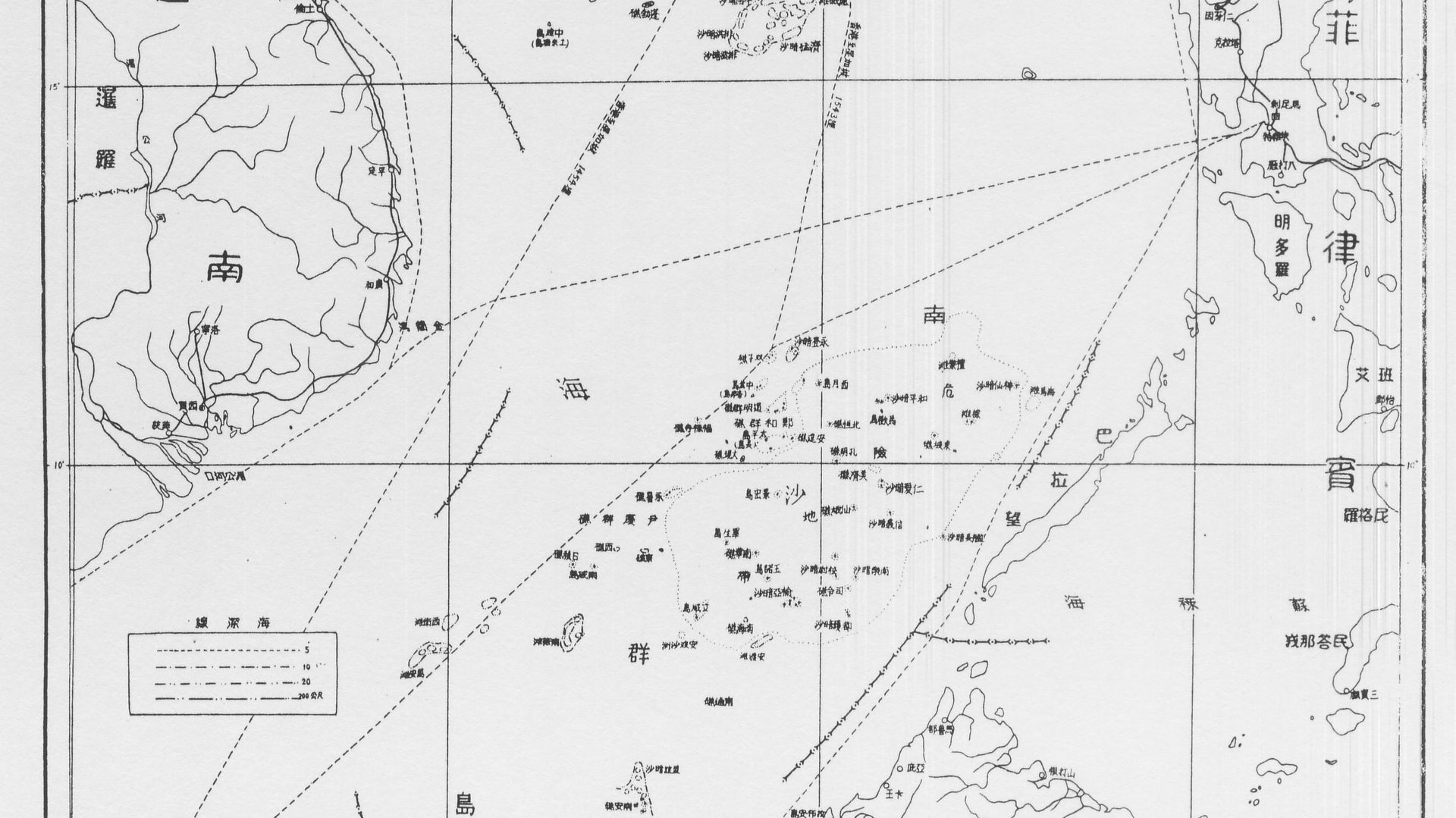

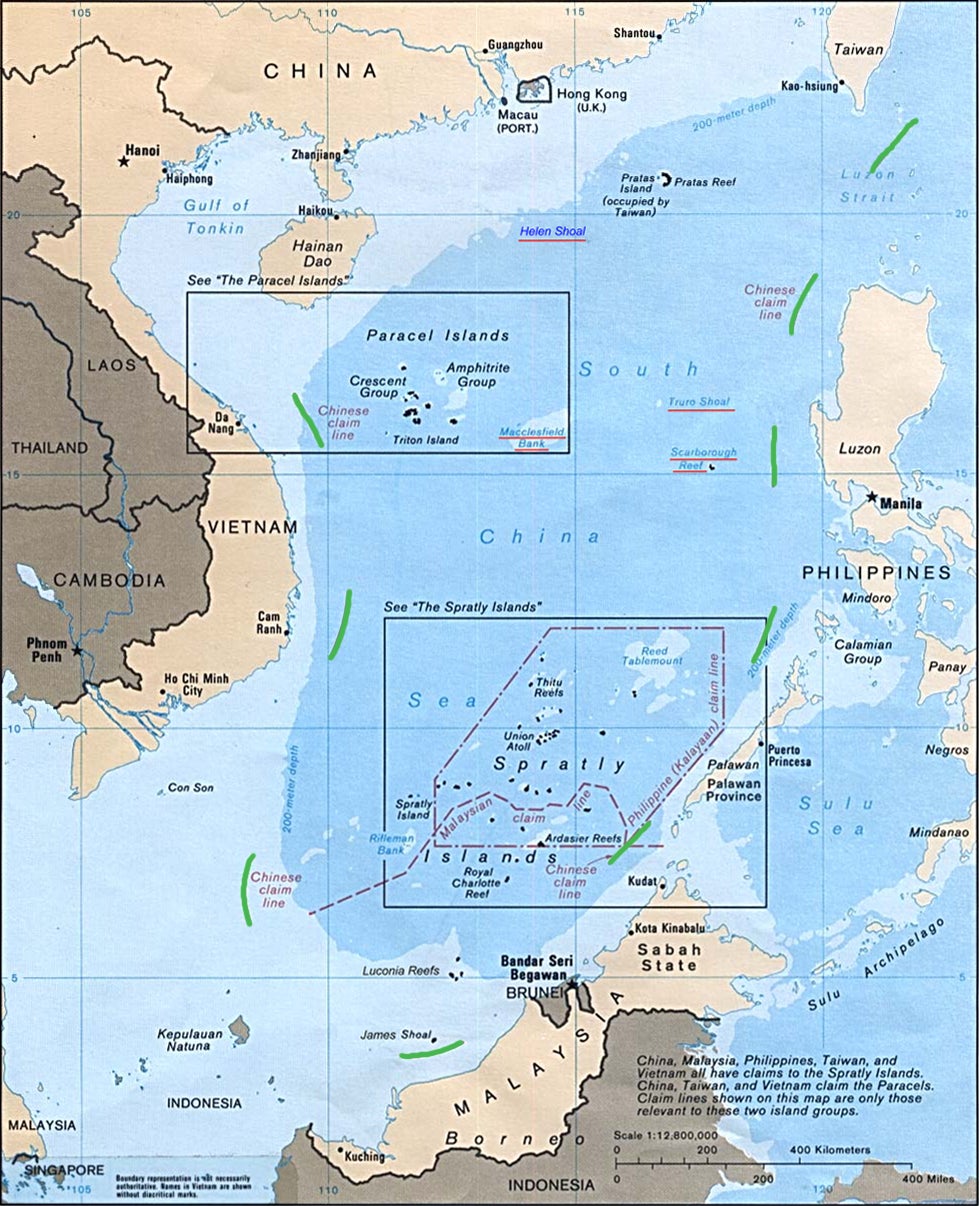

The dashed line was first shown in 1947 on a map entitled “Map of South China Sea Islands” published by the government of the Republic of China. With 11 dashes at the time, it encompassed most of the South China Sea. The Chinese communist party adopted the map in 1949, but removed two dashes to give the Gulf of Tonkin to communist Vietnam as a courtesy (paywall). Within the dashes were key archipelagos—including the disputed Spratly and the Paracel islands—and various other features, including the Scarborough Shoal, a set of coral reefs near the Philippines.

Over the next six decades, little happened with the map. “The nine-dash line was not controversial between 1949 and 2009 because no one ever spent time talking or thinking about it,” notes Julian Ku, a professor at the law school of Hofstra University in New York. “China rarely asserted it publicly.”

But then China submitted the nine-dash-line map to the United Nations in 2009 (pdf), in part to counter a claim by Vietnam over an extended continental shelf and sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly islands. The Chinese map’s accompanying text included this passage:

China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof (see attached map).

Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines objected. They asserted that, among other things, China’s claim was without basis under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos). China signed Unclos in 1996. Other than Taiwan, the other claimants to the sea are signatories too.

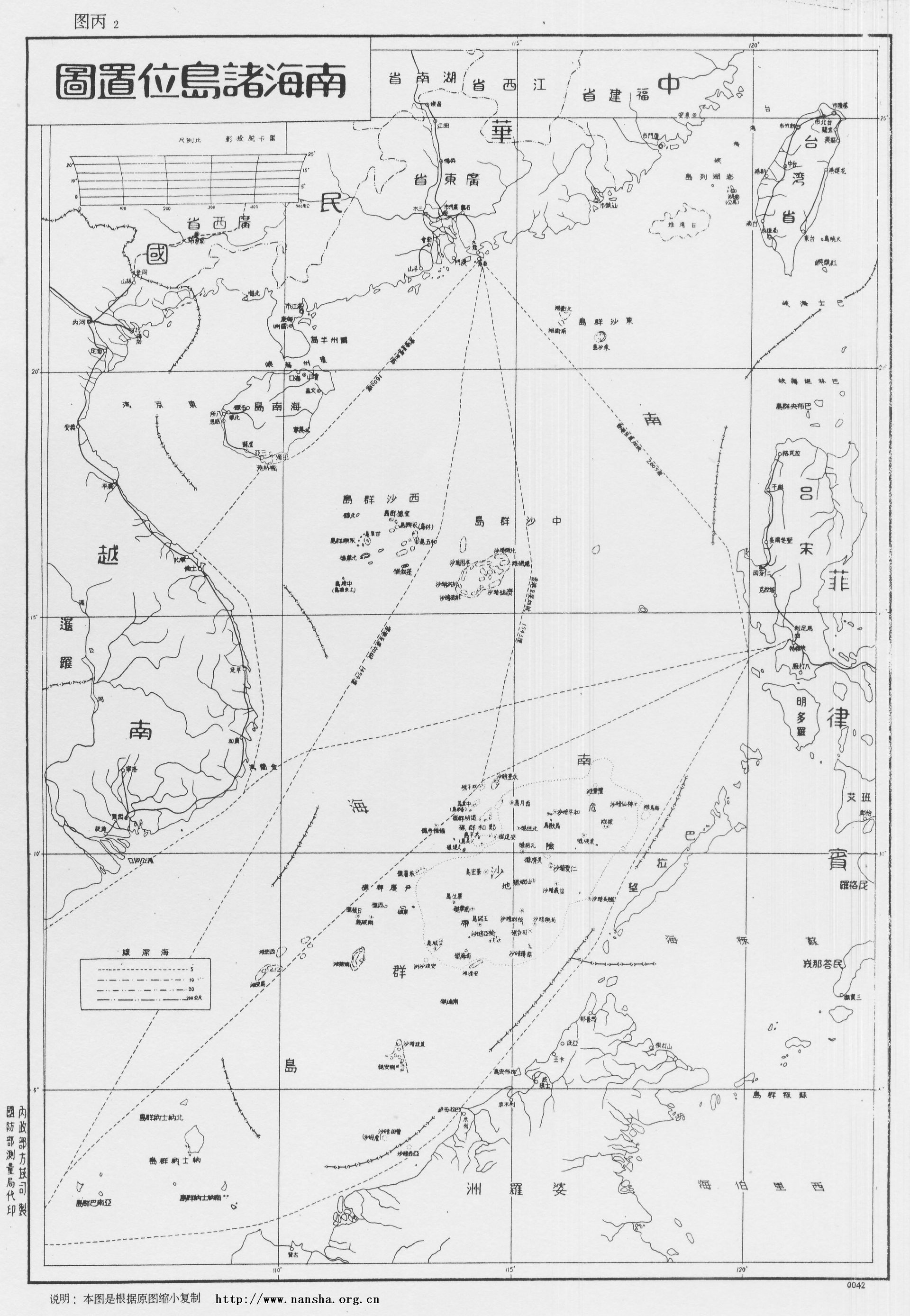

Under Unclos, coastal nations get an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) 200 nautical miles from their shores. In that zone they have sole exploitation rights over all natural resources, though other nations have the freedom of navigation and overflight. The waters within 12 nautical miles are “territorial waters,” where countries have essentially full sovereignty.

An EEZ also applies to the area around a country’s islands too—so whoever controls the Spratlys and Paracels, for instance, also gets a large chunk of ocean to go with them. China’s nine-dash line not only encompasses those strategic bits of rock but also overlaps with several countries’ EEZs.

And in the last few years China has been testing how far it can push those countries and get away with it.

A series of provocations

China’s provocations operate at various levels. The most basic is sending fishing trawlers to fish in other countries’ EEZs. It backs them up with refueling ships—disguised as fishing boats—and even sends its own coast guard to extricate them when they get caught. This sort of behavior has prompted Indonesia, for one, to beef up its military presence and turn to nano-satellites to better track potential trespassers in its waters.

China has also built artificial islands islands in the South China Sea by pumping sand onto live coral reefs and then paving them over with concrete. This kind of action—which also does great environmental damage—gives China a base (paywall) for air and sea patrols.

The next level is to act as if these artificial islands are real land, with their own EEZs and territorial waters. Under Unclos, such artificial islands don’t have maritime rights, and nor do submerged reefs. But in a “freedom-of-navigation operation” in May, the US sent a naval vessel deliberately within 12 nautical miles of the Spratly archipelago’s Fiery Cross Reef, on top of which China has built an island. (It has a runway for fighter jets, a hospital with its own garden, and even a farm with about 500 animals.) In response, China scrambled jets and shadowed the US vessel with three warships, ordering it to leave the area.

The search for some history

While Beijing can point to the 1947 map, it’s struggled to make a convincing case for how it arrived at the nine-dash line in the first place. In a 2008 US diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks, the US embassy in Beijing reported that Yin Wenqiang, a senior maritime law expert with the Chinese government, had “admitted” he was unaware of the line’s historical basis.

That hasn’t stopped the authorities trying to come up with one. In May the state-controlled China Daily reported on a centuries-old book, purportedly owned by a local fisherman, describing ancient fishing routes around various parts of the South China Sea. The report depicted this as proof of China’s rights to the area. A few weeks later, however, when a BBC team went to visit the fisherman to verify the claim, he said he’d thrown the book away because it was too old and broken.

An even more entertaining example was an animated video shared by state broadcaster CCTV on social-media site Weibo, which says that China has had jurisdiction over the sea’s islands for more than a thousand years.

Fuzzy boundaries

Part of the problem with the nine-dash line, however, is that Beijing has never made a specifically defined claim about it. What remains ambiguous, says Ku, is whether its assertion of “sovereign rights” refers to all of the waters inside the nine-dash line, or just the waters within 12 nautical miles of its islands (or what China believes to be its islands).

This calculated ambiguity allows Beijing to strike a balance between antagonizing other countries and maintaining an appearance of patriotic fervor to its domestic audience. It has also helped China with what’s often called its “salami-slicing” strategy—the slow accumulation of small actions, none of which merits a major reaction from other countries, but which over time add up to a major strategic change.

Finally, this fuzziness allows Beijing to keep its options open. In its modern maps China includes a 10th dash east of Taiwan (pdf, page 5). That puts Taiwan within China’s vaguely defined territory. Beijing insists Taiwan is a renegade province. Taiwan considers itself an independent nation, and earlier this year it elected to president Tsai Ing-wen, a pro-independence candidate who prevailed over a Beijing-friendly predecessor.

The trigger point

China reiterated its nine-dash claim in a submission to the UN in 2011 (pdf). But 2012 was when tensions began to ratchet up, says Ku. That was when China effectively annexed the Scarborough Shoal, which falls within the Philippines’ EEZ.

After a standoff between Chinese and Philippine forces, the US mediated a deal in which both sides were to pull back while the dispute was negotiated. The Philippine forces left but the Chinese ones remained, gaining control (paywall) that they still have today.

So in 2013 the Philippines filed a case with the UN’s Permanent Court of Arbitration, in The Hague. It asked the tribunal to rule on various aspects of China’s sweeping claims—in particular, whether the artificial islands and other features China occupies in the South China Sea, such as Fiery Cross Reef and the Scarborough Shoal, are entitled to EEZs or territorial waters under Unclos. This is expected to be addressed in the ruling next week.

The moment of truth—or just more uncertainty?

James Kraska, an expert in international law at the US Naval War College, has written that the PCA probably won’t rule against the nine-dash line directly. In part, that’s because Beijing’s deliberate vagueness about what the line represents makes it hard to legally challenge.

But, he wrote, the tribunal will most likely say that the features China occupies don’t have EEZs under Unclos, and in some cases not territorial waters either. That makes them much less strategically valuable to China. It might give other nations the confidence to conduct their own freedom-of-navigation operations or join US ones, to reassert their rights to the sea. It might also, Ku says, encourage other countries bring their own cases against China to the tribunal.

The fear is about how China will respond. Beijing, which has worked strenuously to discredit the tribunal and refused to participate in the hearings, has insisted it will ignore the ruling—and indeed, there is no international police entity that can enforce it. But China might also feel compelled to demonstrate that it won’t be constrained by the outcome. Here are three things it might do to up the stakes:

- Take control of a shoal in the Spratlys called Second Thomas Shoal, a.k.a. Ren’ai Reef in China and Ayungin Shoal in the Philippines. The Philippines grounded a rusty old warship there in 1999 and staffed it with a few troops as a way of staking a claim. On July 1 a spokesman for China’s defense ministry said China has the ability tow the ship away.

- Start island-building atop Scarborough Shoal. The reef is about 200 km (125 m) from a US naval base in the Philippines, and not much further from Manila. The US and the Philippines have suggested the reef represents a red line, and that any island-building by China there would be prevented with force.

- Set up an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea, as it’s already done in the East China Sea, where it has competing island claims with Japan. In such a zone, unidentified aircraft would be interrogated and possibly intercepted. The US has indicated it will ignore such a zone.

Any of these would be “a real escalation,” notes Corr.

Another possibility, which China has threatened, is to simply pull out of Unclos altogether. Ku says he’d be surprised: “China is seeking to gain international recognition for its delimitation of its continental shelf, and future maritime delimitations with Korea and Japan. It would not be able to use the UN processes for that if it withdrew.”

Corr, on the other hand, believes China could easily withdraw from Unclos. When it signed the treaty in 1996, he notes, it had a much smaller military and more reason to fear bullying from other nations. Now, leaving the system “actually advantages them because they can bully their way into more territory,” he says. “I think they’re now understanding that.” In that case, there’d be nothing at all to stop China muscling its way into more territory in the sea, other than a full-on military showdown.