Joseph Stiglitz on Brexit, Europe’s long cycle of crisis, and why German economics is different

Globalization seems to have a lot more discontents lately.

Globalization seems to have a lot more discontents lately.

From Britain’s vote to extricate itself from the European Union to Donald Trump’s anti-trade and immigration rhetoric, the conventional wisdom about economic advantages conferred by free-flowing goods and capital—and to a certain extent, people—that dominated economic policymaking in the 1990s now faces increasingly stiff opposition in the world’s advanced economies.

Columbia University economics professor Joseph Stiglitz says this shouldn’t be a surprise. The recipient of the 2001 Nobel Prize for economics has long been a critic of the neoliberal conventional wisdom—he calls it “market fundamentalism”—that long dominated at global financial policy-making institutions such as the International Monetary Fund. His best-selling 2002 book, Globalization and its Discontents, chastised the IMF among others for bailout programs conditioned on cutting government debts and deficits. Such austerity programs tended to sink recipient nations into deep recessions, as relatively straightforward Keynesian economics would have predicted.

The book set off an unusually raw debate in the typically rarified world of economic policy-making. Ken Rogoff, the IMF’s chief economist at the time, called Stiglitz’s ideas “at best highly controversial, at worst snake oil.”

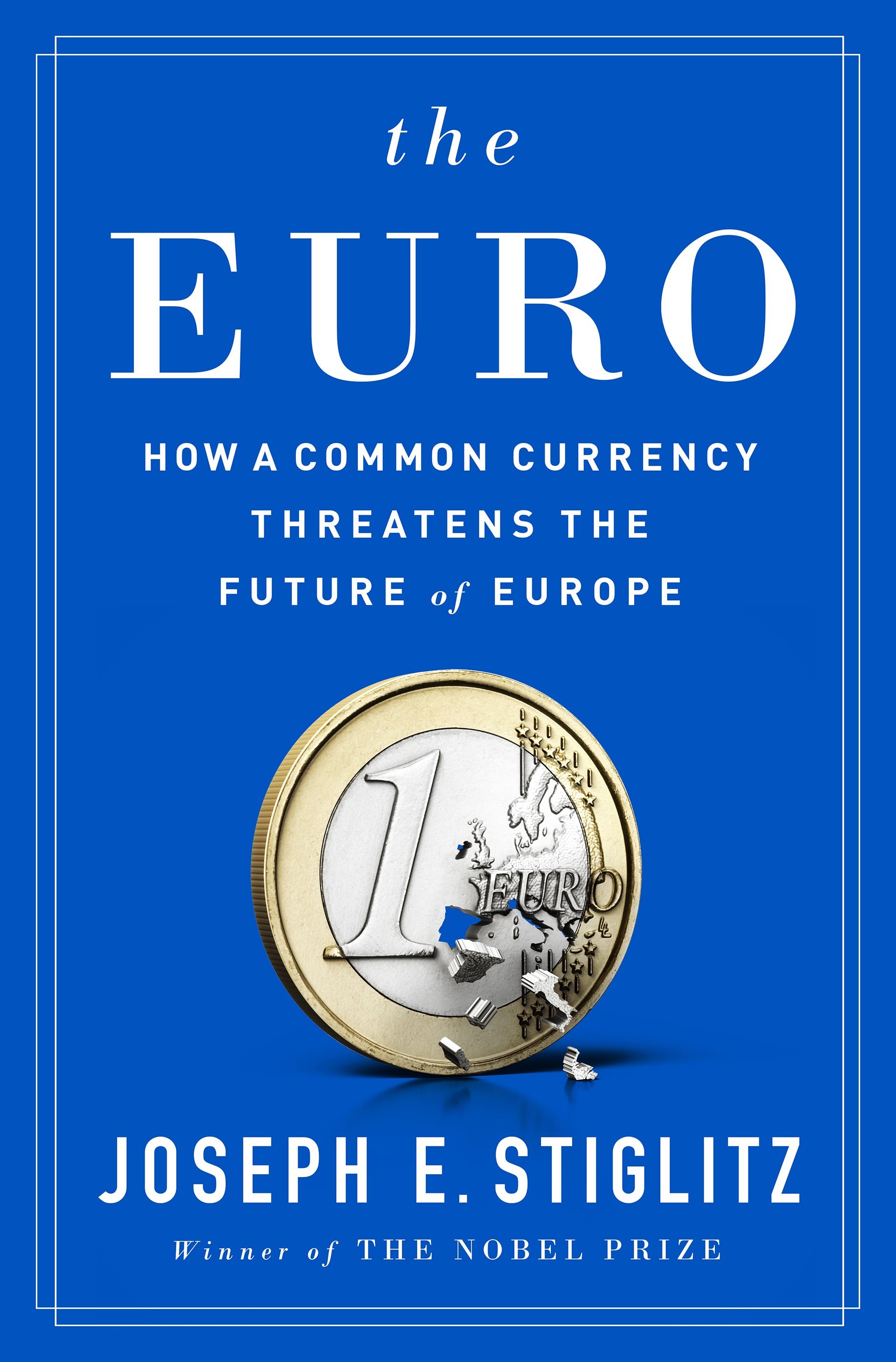

In his new book, The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe, Stiglitz, the former head of the Clinton administration’s White House Council of Economic Advisors, analyzes another transnational economic policy push for austerity that seems to have gone throughly wrong.

From its conception, Stiglitz argues, the euro zone was a project carrying a staggering amount of ideological luggage that effectively blinded its creators to deep flaws in the system. For instance, by adopting a single currency, countries that underwent economic shocks could no longer take advantage of a weaker currency to boost exports and domestic demand.

And in addition to such structural problems, the response of eurozone officials to the debt crisis that erupted in Greece in 2010 has effectively doomed large parts of the monetary bloc to perennial depression. The mechanism is a punishing system of drip-by-drip bailouts, accompanied by demands for steep cuts on spending and disruptive “structural reforms” that only worsen the economic malaise and make it more difficult for a country return to economic expansion. Economic downturns worsen the fiscal position of the country, necessitating more bailouts and deeper spending cuts, and pushing the economy deeper into depression. Rinse and repeat, seemingly ad infinitum.

We visited Stiglitz’s offices at Columbia University recently to talk about his book. In the discussion that followed, he expounded on the depressing state of Europe’s economy, how ideology masquerades as economics, and why Germany has different economics from everyone else in the world. Here’s an edited excerpt of our conversation.

Quartz: How would you describe the moment we’re in now, having been present for the discussions during the neoliberal moment? From my perspective, it seems like it’s kind of coming apart.

Very much so. And with big societal consequences. So, if [in the 1990s, policy makers] had turned to more academic economists, and said, “What will be the effects of free trade? Will it make everybody better off?” they would have been told there are going to be big, distributive consequences.

I’m enough of a political junkie to know if you have large numbers of people much worse off, you’re going to have consequences.

Going back to the founding of the euro zone, it was premised on two ideas. One is that it would bring greater prosperity, and the success of the euro zone would reinforce European solidarity. And then that would lead to the next stages of European political integration.

But it has been an economic failure. And as one would have anticipated, economic failure has contributed to undermining political solidarity. In fact, it’s led to the kind of divisiveness that makes it even more difficult for them to address the new problems they’re confronting like the migration crisis.

So what was the ideology behind the euro? How would you describe it? And what went wrong?

You can analyze the ideology at many different levels. Part of it was an aspect of the globalization ideology. Success required the next step in economic integration, which they interpreted to be a single currency. So the prioritization of a single currency was not based on economic science. It was blind faith.

Was there any backing for it? Where did they come up with this idea?

I think it was the moment of the time. It was just after the defeat of communism, the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was a moment to be seized.

The world could now move closer together. And there were a whole set of initiatives that came together. The WTO was founded in 1995, for example.

So it was a moment of global triumphalism and a wrong interpretation of what the fall of the Berlin Wall meant. It wasn’t the victory of capitalism, it was the defeat of a flawed system.

But there’s a second point that I’d emphasize. Even after you prioritized the notion of this common currency form of economic integration—you can have many other forms—even after you prioritized that, you have to say, “What are the rules the game?”

And that moment happened to be a neoliberal moment, an interesting period of social democratic governments in place in many countries—but social democratic governments that were actually right of center.

So for instance, Gerhard Schröder in Germany.

Tony Blair, Schröeder, and Clinton. From the current perspective many of the [Clinton administration economic policies] you know, financial market liberalization, NAFTA, are all viewed as an agenda of the center right—even though they were governing from the left, as it were.

And so as they developed the rules of the game, they were very much influenced by what I would call neoliberalism and what I call market fundamentalism.

A strong belief in reduced regulation and free movement of capital, labor, and trade.

And that all of that would lead to a burst of economic activity. Don’t worry about inequality. A rising tide lifts all boats. And everybody will be better off. It was almost a continuation of Reagan/Thatcherism, but with a more human face.

One thing that I emphasize in this book was the idea that all monetary policy had to worry about was inflation, that low inflation was necessary and almost sufficient for growth and stability. And so you see that embedded in what you might call the constitution of the euro zone. The ECB’s mandate was just inflation.

So the only thing you had to worry about was keep inflation at roughly 2% and everything else will take care of itself?

When they thought about how are we going to make this disparate group of countries share a currency, they said, “We’ll limit deficits to 3% of GDP, debts to 6% of GDP.”

There was no economic theory behind this. But this was the conservative, neoliberal agenda to constrain the hand of government. And the idea was that governments were the source of instability. If we constrain government, all will be well.

You’ve had really big jobs, you’re around influential people. People whose opinions matter. How do ideas like this that are not backed by theory or practice, how do they get stuck in people’s heads?

That’s a good question. And one that I’ve puzzled a lot about. The first thing that really struck me when I went from academia to the White House was that there was almost no one with a scientific background. They were lawyers. And very, very few of the lawyers had majored in any science.

There is something about the mindset of a scientist that is different—an awareness of uncertainty, modeling, proof. I began my career as a physicist. And in the White House my buddies were the people from the White House office of science and technology policy. But a lot of the people were lawyers. They like winning an argument, but science-based, evidence-based reasoning was just sort of not in their framework.

Has that changed much?

No. Basically, it’s the nature of who gets drawn into political life. I would say if anything, matters are worse because of the distortions to our society brought about by the financial sector.

The financial sector has so distorted salaries that physicists are getting drawn into the financial sector. All that has led to an undersupply of people committed to the public sector. That filters up into the whole system of who is in government today.

Wolfgang Schäuble and people like him, what do they want Greece to do? They’ve lost 25% of their GDP. They’ve moved back to a primary surplus. It just seems almost punitive at this point.

I think that’s in part true. It’s partly punitive. It’s partly “we’ve made a mistake admitting Greece [to the euro zone], let’s get rid of it.”

Germany’s diagnosis is they need more austerity—where in fact, Spain and Ireland had budget surpluses before the crisis, and a low debt-to-GDP ratio. So, totally wrong diagnosis, not good science. And rather than doing analytic work and saying, “Where was the failure?” they go back to their prejudices, their wrong models, and double down.

Are these demands being made for domestic political consumption, back home, say in Germany?

It’s a mixture. What is very clearly true, and I do emphasize in the book, is that German economics is different from economics everywhere else in the world. They still believe in austerity even though the IMF, which is not a left-wing organization, has said austerity doesn’t work. They used to be pro-austerity. And now they say no, it doesn’t work. So they’ve learned. And remarkably, Germany still pushes ahead.

It’s this peculiar brand of economics which has deep popular support, mostly in Germany.

Let’s turn to Brexit. In the context of the intransigence you see from European leadership with regard to the euro zone crisis, how does it fit in?

It fits in several ways. First, obviously, they’re very interdependent. If the Brexit leads to a weaker UK economically, it’s going to lead to a weaker EU and vice versa.

But the way the euro zone handled Greece and Spain was not a manner which would lead one to say, “I want to be a part of that club.” Do I want to be tethered to an economic club where Germany seems to be dominant and so insensitive to democracy and democratic processes in other countries?

That also fed into a perception that the Conservatives have fostered in the UK, of European bureaucrats being very rigid. I think an example of that kind of rigidity that we saw after was European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker’s response to the question of what kind of negotiated agreement [would occur.]

His response was in part, “We’re going to be very, very, very tough with the UK, because we want to make sure that no one else leaves.” But [member states] should believe that the EU and the euro zone are bringing such benefits that no one would want to leave! If the only way you can get people to stay in is to say, “If you leave things will be so miserable. We caught you in a cage and we’re not going to let you out,” that’s not a way you sell.

Especially a project that was supposed to be about democracy.

About democracy, about prosperity, and about solidity. It says, “We have no solidarity. We don’t pay attention to democracy. And we know our system is not working and the only way we can keep you in is by threatening you.”

To me, that response was symbolic of why the EU is not working.