A new study says deep space travel is terrible for astronauts’ hearts

Thinking about taking a trip to deep space? Be warned: it could be bad for your heart.

Thinking about taking a trip to deep space? Be warned: it could be bad for your heart.

Astronauts who have traveled to the moon were four times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than astronauts whose missions were within the Earth’s magnetosphere — the area of space that is controlled by the Earth’s magnetic field — and about five times more likely than those who didn’t travel into space, according to a study published Thursday (June 28) in Scientific Reports.

The Earth’s magnetic field offers protection for human space travelers moving through it, by deflecting charged particles that can enter the body. Astronauts who venture beyond the field are exposed to more deep-space radiation, said the study, which can damage cells and cause arterial clogging.

“Human travel into deep space may be more hazardous to cardiovascular health than previously estimated,” the study authors write.

Several countries, including Russia and China have plans for manned missions to the moon, and the United States is planning a human mission to Mars. Some people are already thinking about how to govern the red planet.

The new findings about heart disease risk aren’t likely enough to derail those plans.

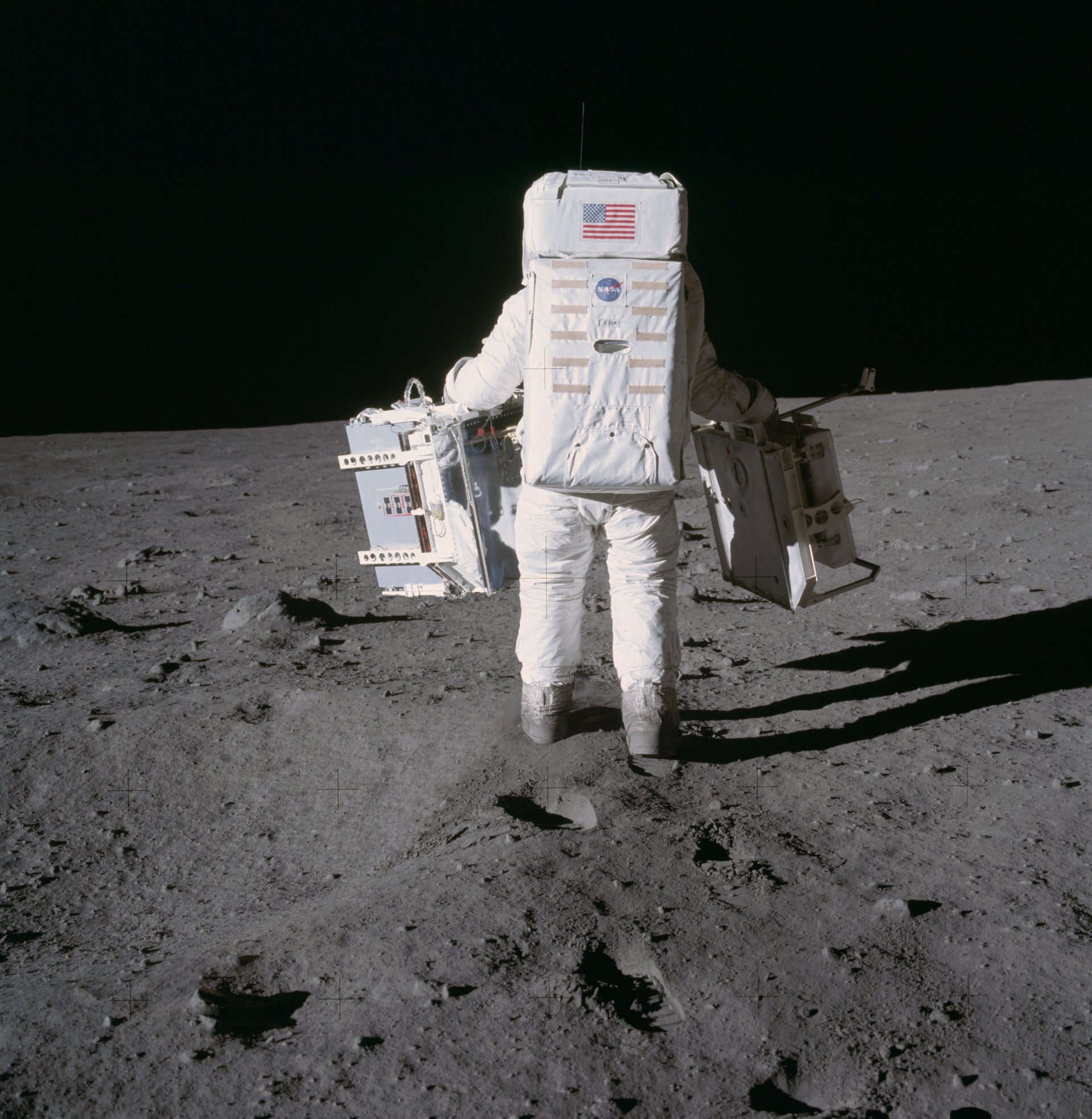

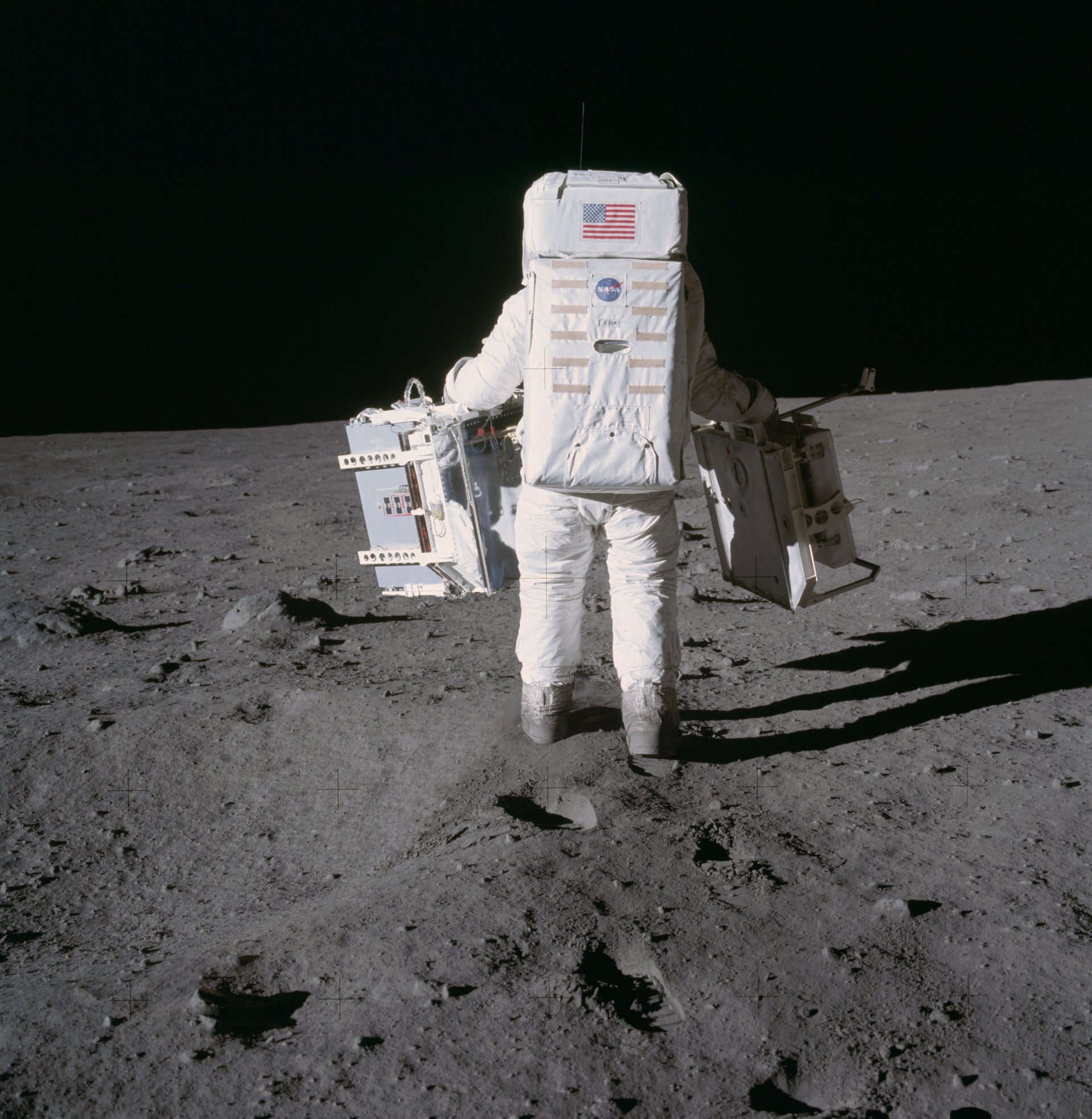

For one, the groups the scientists examined were small. The had to be: only 24 astronauts have ever traveled beyond Earth’s magnetic shield. Scientists examined the causes of death for seven astronauts from the Apollo missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s and found that three of them (43%), including Neil Armstrong, died of cardiovascular disease. That compared with 11% for their sample group of 35 deceased astronauts went on missions that were within Earth’s magnetic field, and 9% for the 35 astronauts who had never gone to space.

The researchers also attempted to recreated some of those deep space conditions on lab mice, to see what sorts of effects they would have in a controlled setting. The mice were subjected to simulated weightlessness and exposed to the same sorts of radiation the lunar astronauts would have experienced. The lab animals were then monitored for six-to-seven months, the equivalent of about 20 years for a human. The mice exposed to radiation developed similar cardiovascular problems to the lunar astronauts.

Michael Delp, the study’s lead author and a physiology professor at the Florida State University in Tallahassee acknowledged the small sample the team examined.

“A lot of studies published both with humans and animals have very small numbers,” Delp told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s the norm rather than the exception, but it means you have to be very cautious in your interpretations.”

NASA, which participated in the study, said it the findings were inconclusive due to the small study size and because family history and diet weren’t taken into account. But it’s a discovery that could help guide additional work on one of the US space agency’s current most important projects: monitoring and assessing health risks for astronauts, including exposure to radiation while in orbit. As NASA gears up for more deep space missions, astronauts’ health while living in space and when they return will become a bigger and bigger issue.