ISIL isn’t merely tolerant of people who speak languages besides Arabic; it needs them

The Islamic State, a.k.a. ISIL, has received a lot of attention for its multilingual propaganda and deft use of social media to terrify and recruit. Until now, however, no one has pulled together a detailed portrait of how ISIL is using its polyglot nature to evolve violent jihad beyond Arabic. This is the second in a three-part series.

The Islamic State, a.k.a. ISIL, has received a lot of attention for its multilingual propaganda and deft use of social media to terrify and recruit. Until now, however, no one has pulled together a detailed portrait of how ISIL is using its polyglot nature to evolve violent jihad beyond Arabic. This is the second in a three-part series.

As violent organizations go, ISIL is one of the most extreme in terms of what experts call its “concept of othering”—namely, how clearly it distinguishes those who are “outside” the group from those who are “in.”

But unlike many extremist groups, it doesn’t rely on superficial characteristics like ethnicity or language to make those distinctions. Its only criterion is obedience to its fanatical version of Islam. “You can be an Anglo and join [ISIL] as long as you adhere to their rules,” says Gina Ligon, a leadership studies scholar at the University of Nebraska, who studies violent extremist organizations. “That’s a unique feature of a terrorist group with strong othering—they draw clear distinctions about who’s an ingroup and outgroup member, but it’s not based on something you can see.”

This means that in the realm of language, at least, ISIL is very different from other terrorist groups, and certainly from its closest relative, al-Qaeda. It isn’t merely tolerant of people who speak languages besides Arabic; it needs them, not only to produce its multilingual propaganda but also to help in managing the would-be caliphate’s increasingly diverse population and to mount attacks outside of it.

Polyglots welcome

For this almost post-national society that ISIL is trying to build, Varvara Karaulova would have been the perfect recruit. A pale, shy, chubby-cheeked brunette, Varvara—or Varya, in the Russian diminutive—studied philosophy at Moscow State University and loved languages and other cultures. This passion was encouraged by her father, Pavel, a businessman who speaks English, French, and Chinese as well as his native Russian. He had brought the family to live in France and the US in the late 1990s when he worked for a small company outside of Boston. So when their daughter began taking Arabic classes in the fall of 2014 and holing herself up in her room to study, her parents didn’t find it odd.

In late May of 2015, went to the university but didn’t come home. After several days, a panicked Pavel talked to her friends and learned that she had been wearing a hijab and long-sleeved shirts to school for months, putting them on after leaving the house. And one day, instead of heading to classes, she’d gone to the airport. A month later, Russian intelligence noted her presence in a Turkish border town, and said she was in a group of Russian women headed to Syria. She never made it there; last June, she was arrested in Kilis, a Turkish border town, was handed over to Russia, and is now in jail in Moscow.

But she would have fitted in well in ISIL territory. Besides the Arabic she had been studying, she also knew Russian, German, and Latin, and was fluent in English and French. Arabic, Russian, and English are the most widely used languages in ISIL territory, and French is common too. With this linguistic repertoire she could have served as a translator for immigrants, a teacher in schools, and a good wife for foreign fighters from many places.

According to Katherine Emily Brown of the University of Birmingham, there’s no evidence that ISIL recruits polyglots like Varya specifically. Even if it doesn’t, circumstances have forced it to take a different stance with non-native Arabic speakers than al-Qaeda did. Mathieu Guidère, a French anthropologist who has studied Francophone jihadis for several decades, says ISIL “has definitely integrated the language component in its strategy,” whereas al-Qaeda had no such thinking about how to incorporate people speaking different languages.

Indeed, according to Guidère, ISIL leaders have taken lessons from an unlikely source: they say they have been “inspired by the ‘Hebrew state’ and the way it deals with new Jews coming to settle in Israel,” he says.

The Israeli model

When a new immigrant comes to Israel, the state typically provides months of Hebrew classes, as well as benefits that include cash, rent subsidies, and health coverage. For a muhajir (immigrant) arriving in ISIL territory, the Ministry of Education has an intensive training program that includes instruction in Koranic Arabic and military terminology; some sessions are available in other languages. (Scholar Aymenn Al-Tamimi posted to his website a document announcing a class given in Kurdish, for instance.)

Some formal classes in standard Arabic are offered, but how regularly isn’t clear. Neither is it clear if it happens in mosques or elsewhere. One person I contacted on Twitter, @AlFinlandi, who claims to be a former ISIL and al-Qaeda member, said that some study independently.

However, the parallel with Israel breaks down because a lot of muhajireen don’t learn Arabic, and ISIL doesn’t try to make them. “It’s by no means the rule that foreign fighters make an effort to learn the local language. Some do, but many don’t seem to bother,” says Thomas Hegghammer, senior research fellow at the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment.

For the most part, not having Arabic isn’t a problem because the muhajireen “barely interact with local communities, because they are established in different and separated areas or houses. They live between each other and communicate rarely with the local population,” says Guidere. Mike Flynn, the former head of the US Defense Intelligence Agency, was quoted in Der Spiegel describing how the ISIL stronghold of Raqqa in Syria had been divided into international zones because of the language issues. “They have put interpreters in place in those international zones in order to communicate and get their messages around,” Flynn said.

With so many multilinguals around, it must be relatively easy to find an interpreter. Varya Karaulova might have gotten a job as one, or as a teacher in a Russian-language school teaching Arabic, or as a member of the Khansa Brigades, a sort of women’s morality police in Raqqa that arrests women who don’t follow ISIL rules. According to posts on the blog “Raqqa is being slaughtered silently,” a certain number of Khansa members for a time were non-Arabic-speaking foreigners.

Indeed, one of the biggest incentives for foreign fighters to learn Arabic isn’t practical but religious. “French foreign fighters are frustrated that they can’t speak Koranic Arabic,” Guidère says. “They want to access the sacred text, but they’re unable to do so.”

Using the language of the enemy

When ISIL does not have polyglots to call on, it turns to English. The language whose homelands are in the demonized West has a surprisingly large role in the caliphate’s territory. Though radical preacher Anwar al-Awlaki once wrote that “Arabic is the international language of jihad,” it seems reasonable that English serves as an unofficial lingua franca when people don’t speak a common language (as it does elsewhere in the world). Indeed, al-Awlaki himself wrote mostly in English, providing a major resource for non-Arabic speakers. (He did, Hegghammer points out, speak excellent Arabic.)

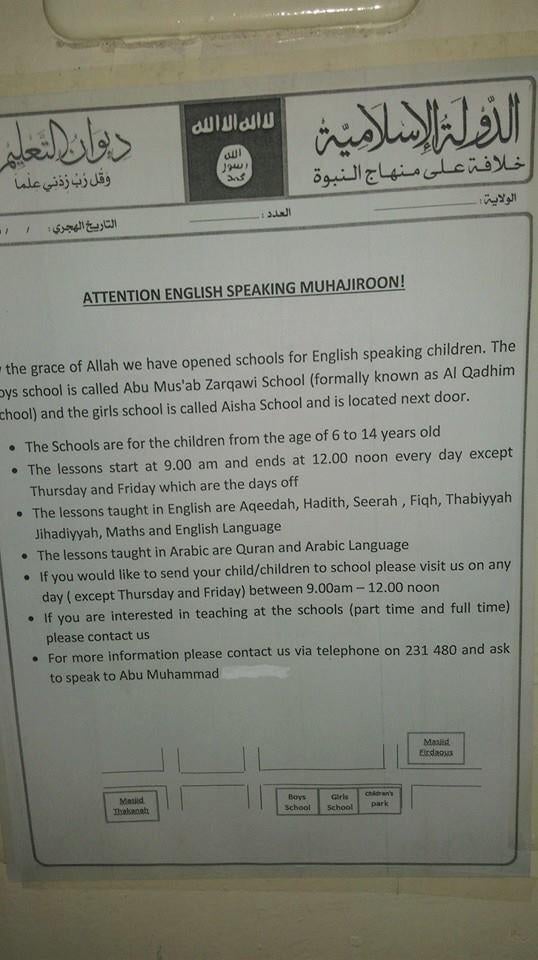

In ISIL territory, English is used for some bureaucratic purposes, and in cities like Raqqa, schools for English-speaking children have opened and ISIL textbooks for the English language have been published. Nurses working under ISIL must be able to speak English, and recruitment calls for doctors require the language. Road signs in ISIL territory reportedly appear in Arabic, Russian, and English.

In addition, ISIL “puts a higher reward structure on English speakers when they’re recruiting foreign fighters,” says Ligon of the University of Nebraska. “People are paid more if they have upper level degrees, speaking English as one of their languages, and having a wife who has an upper level degree.”

Journalist Graeme Wood, who has studied several Arabic dialects and interviewed supporters of violent jihad all over the world, says that though ISIL talks about being cosmopolitan, “in practice there’s a hierarchy of nationality, and English does mark people as being higher in that hierarchy. In that sense, there’s a bit of a status marker.” However, he says, “the status isn’t inherent to the language—it’s about having a passport from a rich country. Language is a good stand-in for a lot of other things.”

Wood says he hasn’t seen any evidence that English is used as a lingua franca, but if it were, it wouldn’t be that surprising. “They’d be surprised you were interested in their use of English because they’d say, ‘Look, there’s nothing in Islam that says you shouldn’t speak other languages, so we’re cool with that.” In fact, a Koranic verse, surah 49:13, extols diversity and even welcomes the Tower of Babel lifestyle. (“O mankind, indeed; We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another.”)

Wood even notes that ISIL members find the language barriers an occasion for solidarity. “I have a sense with a lot of people who go to [ISIL], these language differences, inconvenient though they may be, increase their sense of solidarity and their sense that they’re in it together. The hard work of learning Arabic is just one more thing that binds them together.”

That linguistic “hard work,” as we’ll see in part 3, is present in another unexpected place: ISIL’s leadership promotes people to senior positions even when they don’t speak good Arabic.