Companies headed by introverts performed better in a study of thousands of CEOs

The type of CEO who lands on the cover of business magazines has a big, outgoing personality, all the better to charm investors, win over partners and rally employees.

The type of CEO who lands on the cover of business magazines has a big, outgoing personality, all the better to charm investors, win over partners and rally employees.

But what if companies run by extroverts did poorly? What if companies fared better in the hands of introverts?

What if we knew how the personality traits of CEOs produced different business results, and if boards could hire accordingly?

A new study attempts to find out. The authors, from the University of Chicago, Harvard and Stanford, used linguistic analysis of conference calls to sort 4,591 CEOs of publicly traded US companies into five broad personality traits. Those traits —agreeableness, conscientiousness, extroversion (versus introversion), neuroticism (versus emotional stability), and openness to experience — are known by psychologists as the Big Five and have been used for decades. While they’re not very useful for forecasting an individual’s specific actions and decisions, the Big Five can help predict broad contours about their future.

The researchers found that companies with CEOs who have high scores for openness spend 10% more on research and development, compared to the mean score of all the CEOs examined in the study. CEOs who scored highly in extroversion run companies with a 2% less return on assets. The converse is also true: Introverted CEOs ran companies that outperformed their peers as a whole.

The study has been released as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, but has yet to be peer-reviewed.

Its authors stress that the results show a correlation, not a causation. One explanation for the link between extroversion and poorer returns is that a failing company may seek out a big personality to fix it and that person gets blamed for the ultimate failure, said Steven Kaplan, a Chicago professor who is a co-author. But the results support earlier research suggesting that when a company looks to hire a charismatic CEO, it tends to be disappointed, he said.

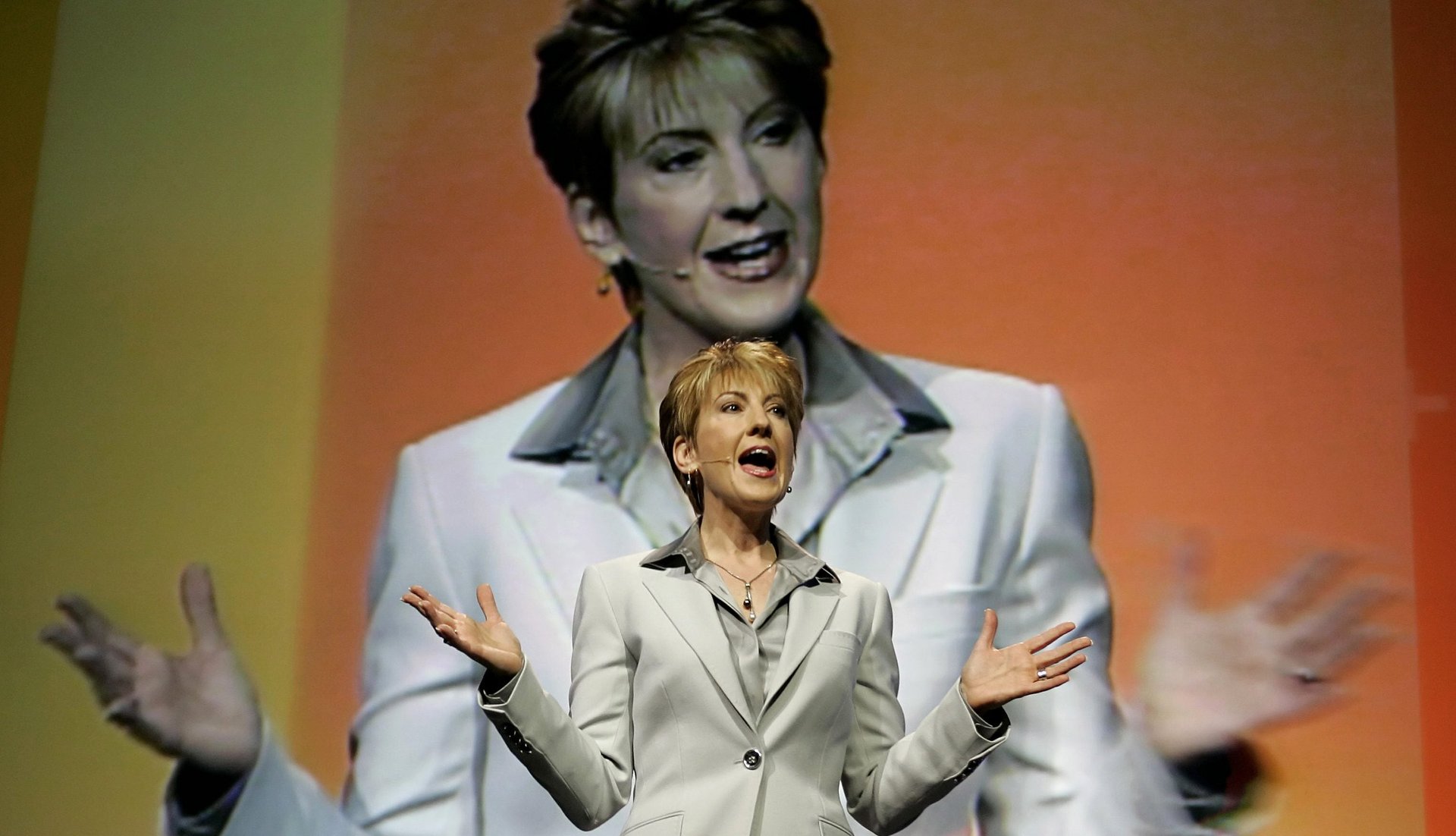

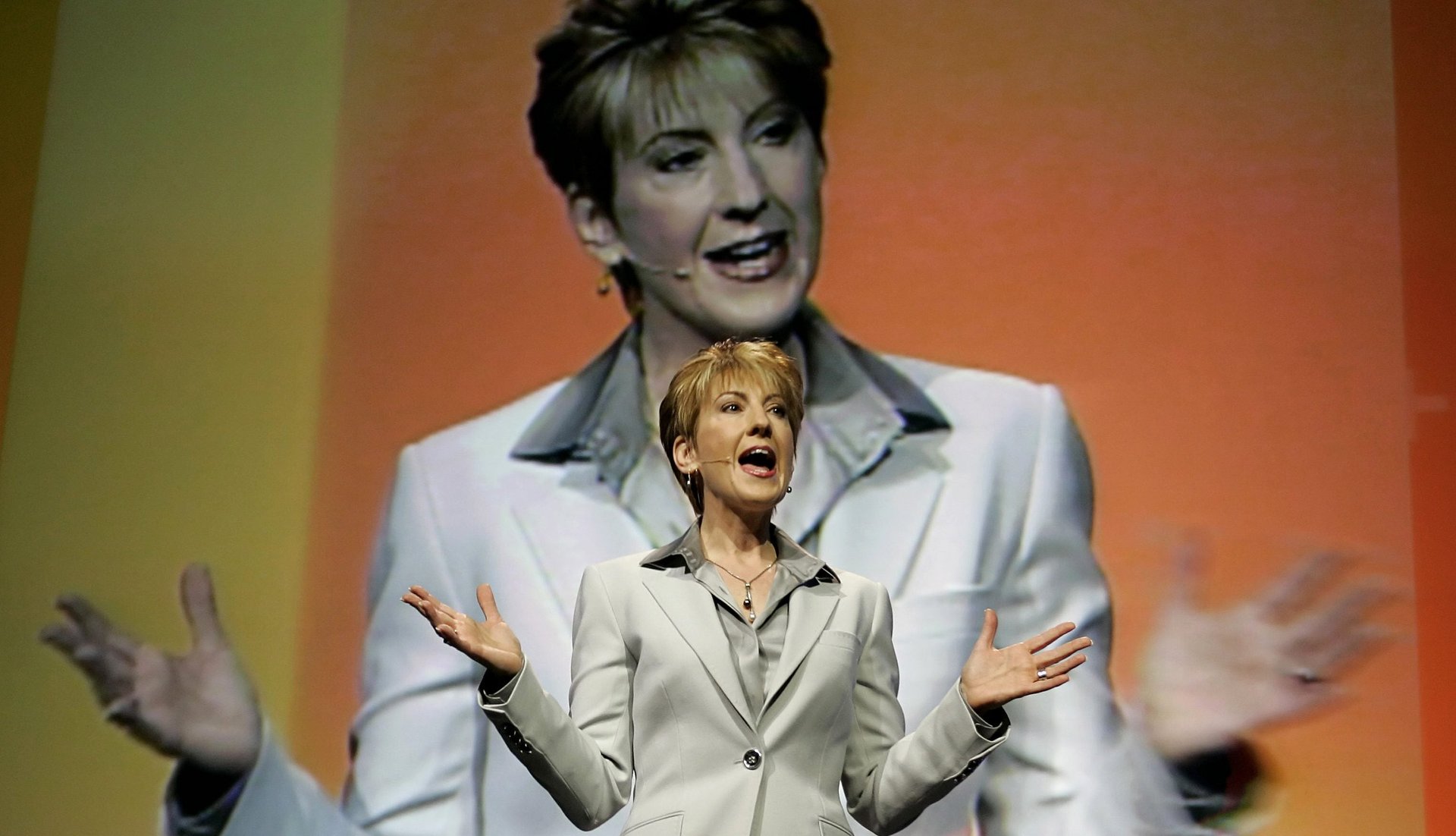

Kaplan pointed to examples like Carly Fiorina at Hewlett Packard, Rob Johnson at J.C. Penney and Bob Nardelli at Home Depot as extroverts hired with fanfare and whose corporate results didn’t live up to expectations.

“At a minimum, you know who goes with what, and what kinds people go with what companies,” he said. ”The next step is figure out if it’s causal.”

The researchers started with in-depth data of 119 CEOs and their personalities based on interviews and surveys of employees conducted for another academic study, and for a management assessment company ghSMART. After they established the relationship between how those CEOs talked and their personality traits, the researchers were able to statistically predict the personalities of other CEOs.

For example, CEOs who use the first person singular, lots of adverbs and many words per sentence tend toward neuroticism, while CEOs who favor words with more than six letters, hesitate and use qualifiers score highly for conscientiousness. The authors then took those linguistic groupings and applied them to the transcripts of the Q&A sessions on 70,329 corporate earnings conference calls conducted by thousands of company chiefs.

One flaw in the the study is that it only looks at CEOs, and therefore doesn’t consider whether there are qualities they share that aren’t present in the rest of the population, said Patrick McKnight, a psychology professor at George Mason University who writes about the use and misuse of data.

“All of the studies on outstanding people typically depend on the outcome,” McKnight said. “CEOs got there for a reason. We need to know about the people who didn’t make it as CEOs.”

Still, Kaplan says the research, as preliminary as it is, might serve was a warning to corporate boards attracted to CEOs with big personalities.

“Be careful about hiring the person who is extroverted, and along with that personality, make sure they have a reputation for getting things done,” he said.