Letting ADHD go untreated can lead to high levels of reckless sex and drug abuse

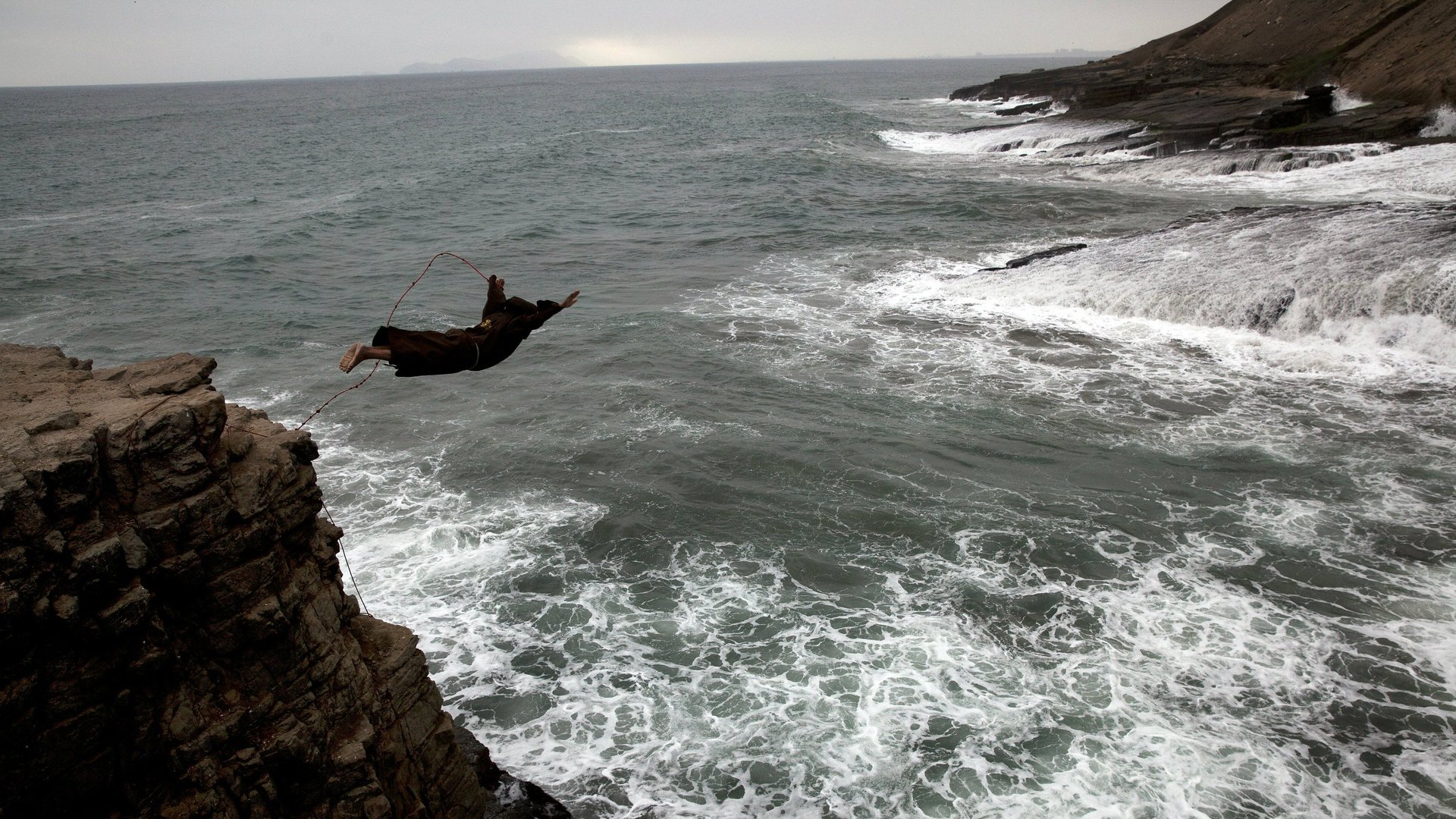

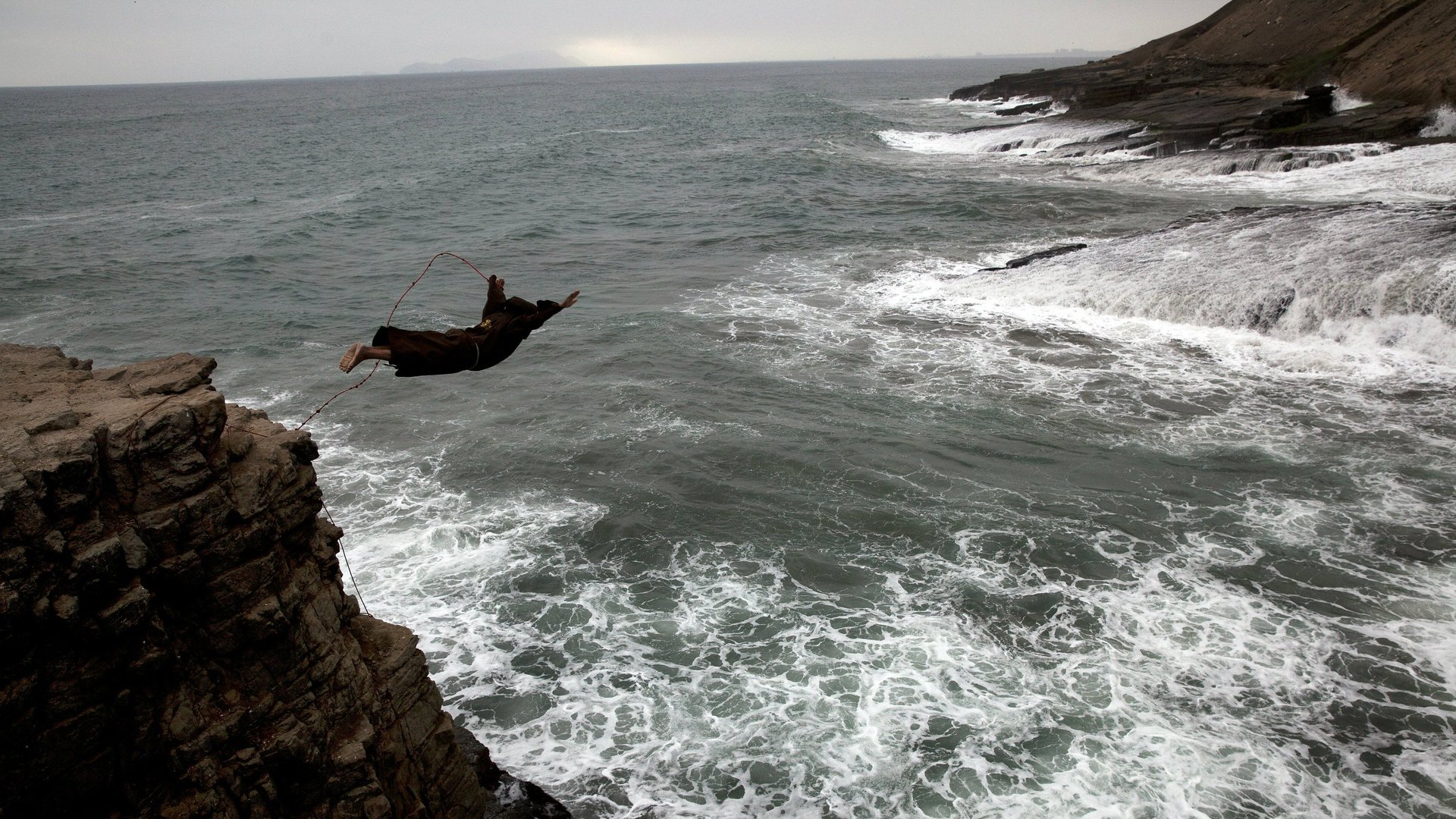

Kids with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often have trouble with self-control, making it harder to do well in school and sustain healthy relationships. That deficit of self control can lead kids with the ADHD to engage in riskier behavior than kids who don’t have the condition. This includes reckless driving, unprotected sex, and drug abuse.

Kids with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often have trouble with self-control, making it harder to do well in school and sustain healthy relationships. That deficit of self control can lead kids with the ADHD to engage in riskier behavior than kids who don’t have the condition. This includes reckless driving, unprotected sex, and drug abuse.

New research shows that medication might help to curb that risk taking. According to Medicaid claims for about 150,000 children diagnosed with ADHD in South Carolina between 2003 and 2013, kids who were medicated were 3.6% less likely to contract a sexually transmitted disease than non-medicated kids, 7.3% less likely to abuse drugs and 2.3% less likely to get injured.

ADHD is one of the most pervasive mental health condition kids today face. About 11% of kids between the ages of 4 and 17 have been diagnosed, with about 70% of them taking medication to treat the condition. But while some studies show medication can help to control hyperactivity and impulsivity, others have shown it can lead to lower grades and worse parental relationships.

Research from Janet Currie, a Princeton economist, used data from the 1994–2008 National Longitudinal Survey of Canadian Youth, and found medical treatment was associated with worse academic outcomes including repeating a grade and poor scores on math tests, as well as worse parent-kid relationships (the study used a change in insurance coverage of ADHD drugs in Quebec to measure the impact of treatment on emotional and academic outcomes).

Patricia Quinn, a developmental pediatrician and author of many books on ADHD, said this research overlooks the fact that medication can help you concentrate, but improving grades or your relationship with your parent means learning new skills.

“It will improve your concentration, but its doesn’t teach you the skills of how to get along with each other, or how to get organized in school.”

Quinn said the latest research from Princeton was critically important because people significantly underestimate the health risks associated with ADHD. “People think it’s an elementary school disorder, they don’t get good grades, or they aren’t invited to the birthday party, but they don’t understand the havoc it wreaks in the life of individuals,” she said. People with ADHD die earlier, try to commit suicide more often and get in more car accidents, she said.

In the 1970s, Quinn screened 300 boys with ADHD and picked the most hyperactive 100 to follow for three years. Five years later, three of them were dead. “This study shows we can decrease those numbers.”

The research looked at the probability of risky sexual behavior outcomes (STDs and pregnancy), substance use and abuse disorders, and injuries, concluding that taking medicine reduced the probability of each area of risky behavior.

Other studies also show benefits to medicating kids. In the early 1990s the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health randomly assigned 579 ADHD-diagnosed children age 7–9.9 years old to 14 months of treatment. It found that just medication, and medication and behavioral therapy significantly reduced inattention and hyperactivity, the core symptoms of ADHD. There was no significant difference in academic performance, social skills and parent–child relationships between those who were treated and those who were not.

A separate study, conducted with Danish data, found treatment was associated with fewer hospital visits and fewer run-ins with the police, similar to the Princeton research.

Figuring out the effectiveness of medication is important because diagnoses of ADHD are rising, as are the costs of treating it. Between 2003 and 2013, Medicaid spending on ADHD prescription drugs rose by 296% in South Carolina (in 2013 dollars), reflecting more people getting treatment and higher prices for the drugs, the study said.

And studies like this raise awareness that ADHD is not just about hyperactive kids, but people who face higher risks throughout their lives.