The 4.3 million Americans whose race could change when they die

We all carry expectations about our own deaths: to be respected, mourned, missed, by at least a few; some kind of cultural ceremony or ritual; a few last wishes dutifully carried out. What you might not expect is to be assigned a new race.

We all carry expectations about our own deaths: to be respected, mourned, missed, by at least a few; some kind of cultural ceremony or ritual; a few last wishes dutifully carried out. What you might not expect is to be assigned a new race.

In the US, there are two people responsible for filling out government paperwork about you, after you die: a medical certifier and a funeral director. The medical certifier records details like cause of death. But in many states it’s the funeral director who’s responsible for completing biographical sections: where you died, your educational background, occupation, race, and ethnicity.

These arbiters can produce some strange final records. Research conducted over the last decade by the US National Center for Health Statistics shows that people of Asian, Hispanic, and especially Native American descent stand a surprisingly high chance of being mislabeled when they die.

Official US race and ethnicity demographics are tracked by self-reporting—that is, census. Every 10 years, Americans fill out paperwork that lets the government know what race they consider themselves a part of, and whether they are of Hispanic origin.

After you’re dead, the person most qualified to state your race and ethnicity is still you. But, well, you’re dead. So according to the government, it’s up to funeral directors to submit that information for you.

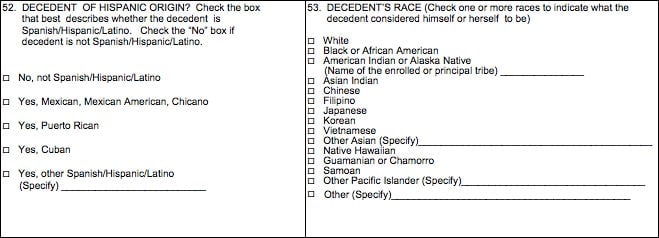

Though each state might have slight variations on their certificate, the US government provides a standard for them to follow:

For black and white Americans, this system seems to work. Research finds that mortality records for black and white people in the US are accurate: They match what people say in census data.

But for some minorities, not so. In a study published this month by the National Center for Health Statistics, a part of the Centers for Disease Control, researchers looked at 3.8 million representative death records. They found that for deaths from 1999 to 2011, 3% of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander populations ended up misclassified as other races.

An astonishing 40% of American Indians and Alaska Natives were also found to be misclassified, as STAT News pointed out earlier this week. The majority of deceased from those populations were misclassified as white, perhaps in part because interracial marriage among American Indians is particularly common, and people might appear more white.

For Hispanic and Asian populations, this is actually good news: 3% is down from 5% and 7% misclassification, respectively, for deaths between 1990 and 1998. But if the current levels of error were to stay the same for these groups in the next 10 years, that could mean roughly another 4.3 million misidentified Americans.

“Historically the white and black populations in this country are very well known,” says lead author Elizabeth Arias. “People are very accustomed to the whole black/white dichotomy, so it’s easier to identify.”

But the failure to accurately record deaths of people who are not black or white can impact life expectancy estimates for different populations, and in turn, our understanding of public health needs. In essence, says Arias, we’re missing information on 40% of American Indian deaths.

Funeral directors are instructed to question the deceased’s family to fill out the certificate, but Arias believes that race is a more delicate topic than profession, for example. Out of sensitivity or a sense of etiquette, some directors might refrain from asking and guess based on what they see. Arias believes one of the major reasons for errors involves funeral directors who have to identify race and ethnicities they’re not used to seeing. Her data show that in areas with smaller American Indian populations, for example, more mistakes occur.

The study doesn’t account for people misreporting their age, or for changes in how they self-report on their race and ethnicity.