The Berlin Wall was built 55 years ago today, and it should remind us that walls don’t work

On the 55th anniversary of “barbed-wire Sunday,” as the start of construction on the Berlin Wall is known, the border security business is booming.

On the 55th anniversary of “barbed-wire Sunday,” as the start of construction on the Berlin Wall is known, the border security business is booming.

Donald Trump has made a wall on the US-Mexico border a controversial centerpiece of his presidential campaign, and EU countries have erected fences to keep migrants and refugees out. But the Berlin Wall anniversary should be a stark reminder: Walls can only contain people for so long.

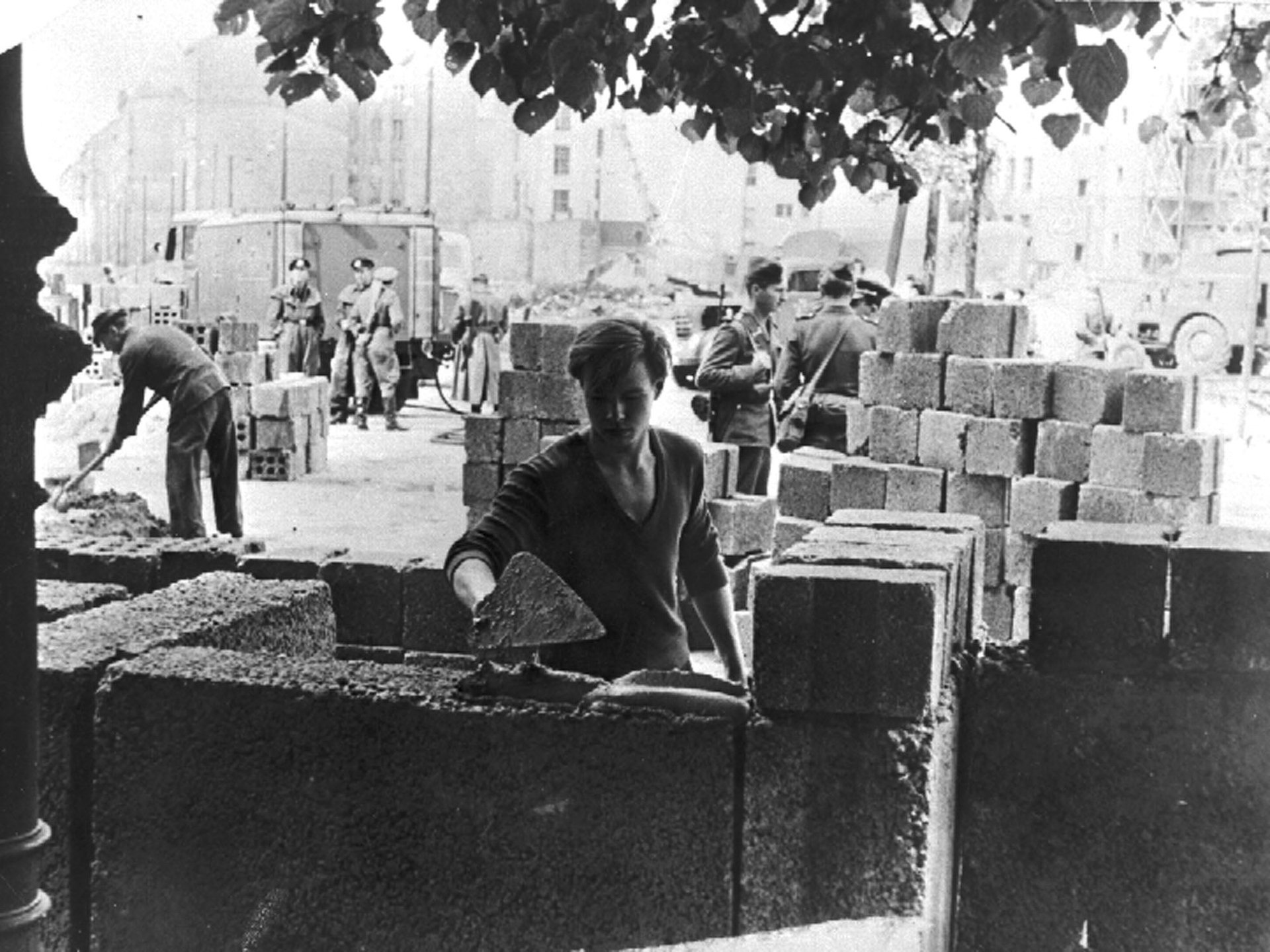

On August 13, 1961, just before midnight, the National People’s Army and the People’s Police of the German Democratic Republic began rolling out a barbed-wire barrier to close off the Communist-controlled eastern sector of Berlin from the Allied-occupied west.

It was the beginning of a cruel divide that would tear apart families and friends, ruin lives, and create repercussions that are still being felt by Berlin today. Almost 28 years after the wall came down, Germany’s capital remains economically disadvantaged from its divided years, while buildings in the former East still show the scars of neglect under Communism.

“Stacheldrahtsonntag”—barbed wire Sunday—was the first step in constructing a wall that would physically separate a city that had already been divided politically since 1949, after World War II. The British, American and French zones merged to become the Federal Republic of Germany (BRD or Bundesrepublik Deutschland). The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic (DDR or Deutsche Demokratische Republik), and left Berlin marooned geographically in communist-controlled East Germany.

As the two sides lined up, the BRD with what would become NATO and the DDR joining the Warsaw pact countries—the Soviet bloc’s military alliance— the Iron Curtain of the Cold War would soon have its physical manifestation in Berlin.

East Germany had been bleeding citizens since the city’s divide. An estimated two million left for the more prosperous west between 1949 and 1961, and the DDR’s economy was under threat. Walter Ulbricht, the DDR head of state, said at a press conference in East Berlin: “Nobody has the intention of building a wall.”

Just a few weeks later, the wall was a reality, and Ulbricht changed his tune: “We have sealed the cracks in the fabric of our house and closed the holes through which the worst enemies of the German people could creep.”

The Wall, which the DDR called the “anti-fascist bulwark,” took shape quickly, with concrete slabs replacing the barbed wire, sealing off West Berlin from East Germany to a total length of 91 miles (155km).

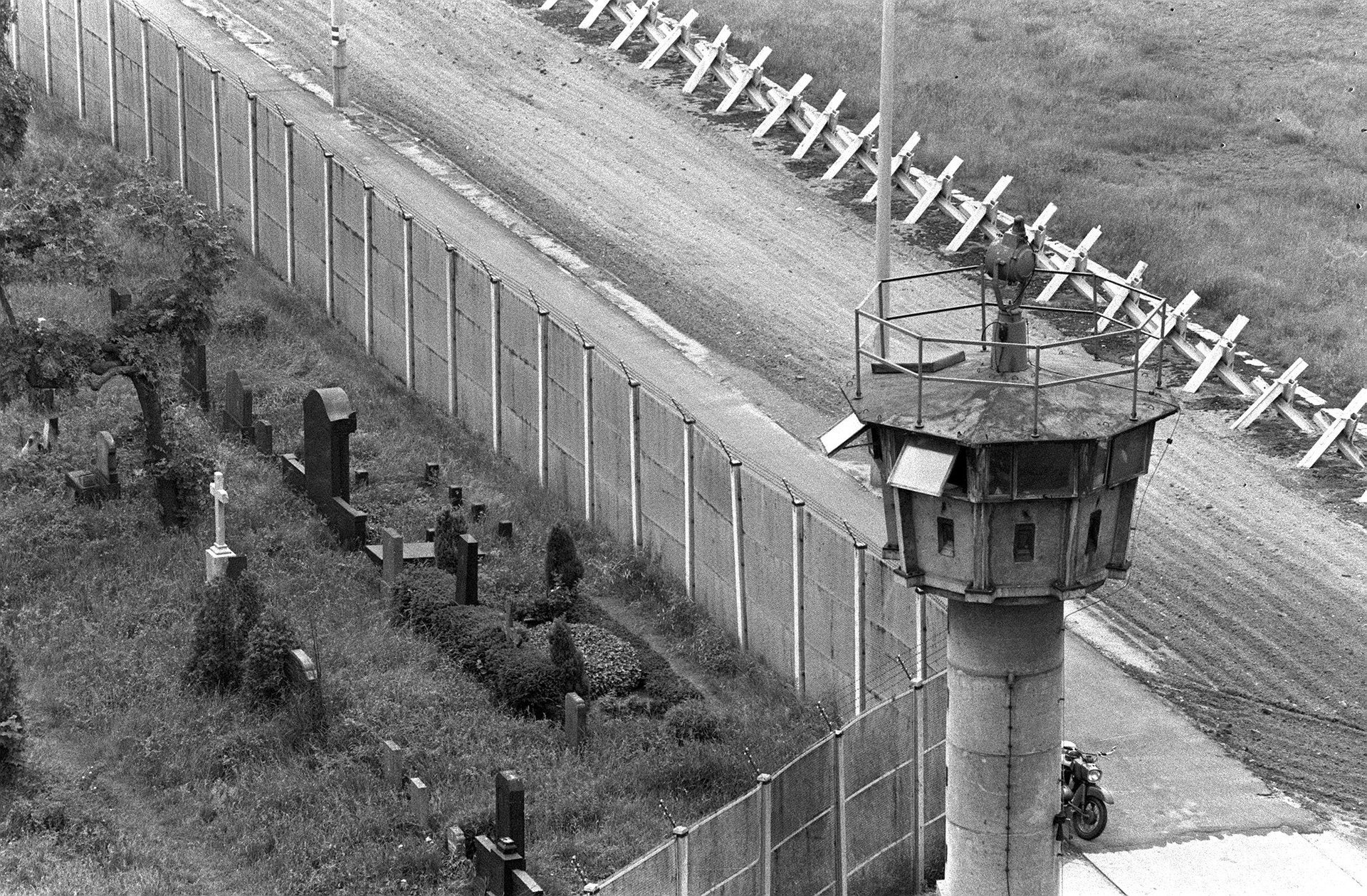

The 11ft walls—there were actually two—between the eastern and western halves of the city stretched 27 miles, and buildings that abutted the Wall on the east had their windows boarded up. Over 300 watchtowers overlooked a “death strip” between the two barricades, which had guard dogs, floodlights and trip-wire machine guns.

At least 138 people died in failed attempts to escape across the Wall, according to the Berlin Wall Memorial Site and Documentation Center, but others put the number at over 200.

The first victim, a 59-year-old nurse named Ida Siekmann, died just nine days after the Wall was put up. She had thrown down a mattress from the window of her third-story apartment and jumped, dying of her injuries on the way to the hospital. Escape methods over the ensuing years ranged from hot air balloons and inflatable mattresses, to a zip line and a tight rope.

But beyond the DDR’s economic reasons for erecting a wall and manning it with soldiers ordered to shoot on sight, the Wall symbolized an ideological rift between leaders on how Germany should be led—democracy and capitalism or communism.

Why did the Western allies let the Wall happen in the first place? At the time, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev wanted western forces to leave Berlin, but US president John F. Kennedy refused. Allowing the Wall to be built was at the time preferable to war with the USSR, and protected the people of West Berlin.

In his book The Berlin Wall: A World Divided 1961-1989, Frederick Taylor, a British historian specialising in modern German history, quotes Kennedy’s special assistant Kenneth O’Donnell, who reported that the president said at the time: “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war. This is the end of the Berlin crisis. The other side panicked—not we. We’re going to do nothing now because there is no alternative except war.”